Inspired by birds, made for humans

Updated: 2013-06-30 07:36

By Penelope Green(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

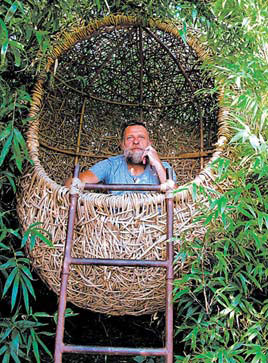

Willem "Porky" Hefer sitting in one of the nests he has made. |

|

Whorls of eucalyptus form Jayson Fann's spirit nests in Big Sur, California. Drew Kelly for The New York Times |

BIG SUR, California - Woven from eucalyptus branches, the nest bloomed high on the side of a cliff overlooking the Pacific Coast Highway, a great whorl of sticks atop four gnarly pillars. The north wind hissed through the gaps in the branches, the stars were visible through the nest's oculus entry and elephant seals could be heard far below honking and braying in a lullaby like no other.

Designed and built by Jayson Fann for the Treebones resort here, the nest, which costs $110 a night, is always booked. There have been nest marriages and, inevitably, nest babies.

From New Age cocoons and backyard playthings of the rich to public installations made from the wood of hurricane-felled trees to contemporary art objects, human nests are drawing attention.

This spring, Willem Hefer (known as Porky), a South African nest maker who was formerly a creative director at the marketing communications agency Ogilvy & Mather and Bozell, took his nests to design fairs, from Design Miami/Basel and Collective .1 in Manhattan to Design Days in Dubai.

Chee Pearlman, a design consultant and curator, ventured that nests are "probably the purest antidote to the heavy steel-and-concrete building footprints that, city by mega-city, are overtaking the globe." Prehumans, of course, were born in nests, and we used to be pretty good at making them. Great apes like chimpanzees and bonobos still make complex and lovely ones.

Fine artists do love a nest. The elder statesman of the form is Patrick Dougherty, the itinerant installation artist whose snarls of sticks and twigs have been built into the landscapes of cultural institutions around the world. Kinetic and animate-looking, they are made from local plant material and are designed to decay like a tumbleweed on an open plain.

Performance artists are continually "proposing" the nest. In March, Gareth Wynne Fitzpatrick, an English artist, made a nest as birds do, sort of. He used climbing gear to hang from the ceiling of the Mediamatic gallery in Amsterdam as he fashioned an intricate and enormous willow globe, taking care, he said, to employ the same knots used by weaver birds. He also said that he has been unable to sit in the nests he has made (this was his second). "Unless you can fly, they are inaccessible," Mr. Fitzpatrick, 40, wrote in an e-mail. "Very useful for deterring snakes."

Mr. Hefer, 45, came to nest-building after he soured on advertising. He was a fan of Buckminster Fuller and "Shelter," the'70s era counterculture bible of do-it-yourself building, and a keen observer of the indigenous building styles of his country. He has designed cane nests woven by blind people, nests made from the plastic strapping around shipping containers and nests of recycled tires and leather off-cuts. His leather nest sold for $17,000 to a Formula One driver who saw it at the Basel art fair.

Roderick Wolgamott Romero, an artist and musician, has been making nests since the mid-1990s, when he built his first as an art project and suspended it from a nine-meter-high maple tree in Olympia, Washington. In 2004, during an installation of a 900-kilogram art nest at the Modern Art Museum in Tacoma, Washington, he spent a night in that first nest in nearby Olympia, woke up in the middle of the night thinking he was still at the museum and fell to the ground. Although he broke his back, he has since made about two dozen nests including nests for a Laurie Anderson project in Switzerland, a community nest in a garden in New York's East Village and a $70,000 nest for the son of a wealthy executive in Los Angeles. In May at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, he built a nest out of wood salvaged from trees downed in October by Hurricane Sandy. It is a rougher piece than his usual delicate structures.

Recently, Mr. Romero, 48, mused on the age-old question of which came first, the chicken or the egg? To which he answered, "The nest, of course."

Mr. Dougherty has never slept in any of his creations, which take about three weeks to construct. "I guess by the time I've finished working on them," he said, "I'm really tired of them."

The New York Times

(China Daily 06/30/2013 page9)