Antiquities survive thievery

Updated: 2013-07-28 08:29

By Elisabetta Povoledo(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

PERUGIA, Italy - As tomb heists go, it was an odd job.

The robbers were not professional tombaroli, the looters of ancient sites who have over the centuries despoiled countless graves in Italy. They were people, the authorities said, who had stumbled onto a trove of important Etruscan artifacts a decade ago while digging to build a garage in a villa just outside the city center here.

Rather than notify authorities, investigators say the looters divided up the stash and looked around for years before trying to cash in on their good fortune.

But two years ago, when the police were searching a home in Rome, they turned up a photograph of what appeared to be an illicit artifact. That investigation led them to Perugia, and when the looters appeared ready to sell the artifacts this year, the police moved quickly.

"We didn't want to risk losing track of them" because "very important pieces like this would likely have ended up abroad because they are difficult to sell in Italy," said Major Antonio Coppola, one of the investigators.

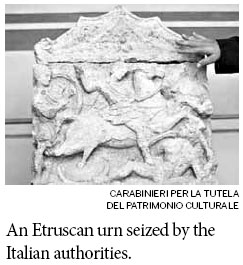

The 21 delicately carved travertine marble urns dating to the Hellenistic period were seized recently by the Italian authorities. Under Italian law, they are now property of the state and will eventually be installed in Perugia's archaeological museum.

But archaeologists bemoan the fact that they still lost something precious: the context in which the artifacts were found.

In covering their tracks, the looters effectively wiped out the sort of information - the size of the tomb, the number of rooms, how the various urns and other artifacts were arranged - that scholars scour for information to reconstruct ancient civilizations.

"And we still don't know where the tomb was - we think they built over it," said Luana Cenciaioli, a local official with the cultural heritage authority, which has begun an exploratory dig in the area where it believes the tomb was located.

Italy's artifact-rich soil is forever delivering up evidence of past civilizations - when foundations are laid, or new roads or sewers are built - and authorities have long struggled to counter the trafficking of such artifacts.

Still, heightened investigative activity and high-profile Italian court cases have dampened the market for looted artifacts, and museums around the world have tightened the rules on how they collect antiquities.

The urns confiscated this year were identified as belonging to the Cacni family, a wealthy local clan, and date from the third and second centuries B.C.

No one has been arrested or named in the case, but investigators have identified five suspects. They could face up to 10 years in prison. But the case still might not get to trial because the statute of limitations for the crimes of which they are suspected - illegal excavation and receiving stolen goods - may run out.

Ms. Cenciaioli said that the quality of the urns made the police recovery a special moment. "They are among the finest ever found," she said.

Had the discoverers notified the authorities when they stumbled upon the tomb, they could have benefited from a finder's fee - 25 percent of an object's market value for the person who found it, and 25 percent to the person on whose property it was found.

Ms. Cenciaioli estimated that the average market price for an urn would be around 40,000 euros (about $52,000), meaning the finder's fee could have topped 10,000 euros (about $13,000) for one urn.

She said, "It can add up to a tidy sum."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/28/2013 page12)