Fukushima disaster deepens with new errors

Updated: 2013-09-15 07:31

By Martin Fackler(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

NARAHA, Japan - In this farming town in the evacuation zone surrounding the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, workers in surgical masks and rubber gloves are scraping off radioactive topsoil in a desperate attempt to fulfill the government's vow to allow most of Japan's 83,000 evacuees to return. Yet, every time it rains, more radioactive contamination cascades down the hillsides.

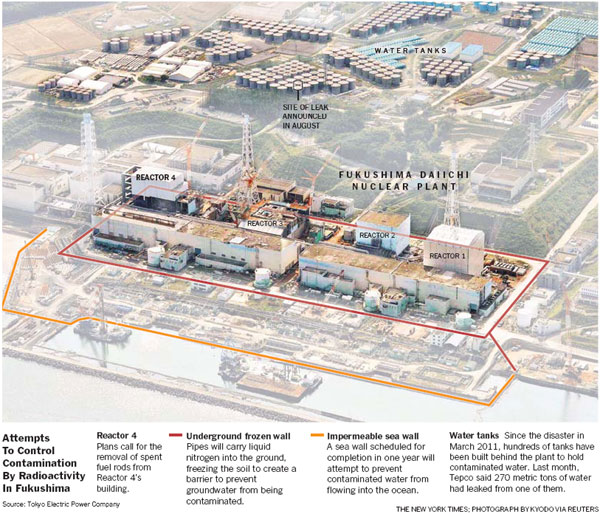

Thousands of workers and a small fleet of cranes are preparing for one of the latest efforts to avoid a deepening environmental disaster: removing spent fuel rods from the damaged Number 4 reactor building and storing them in a safer place.

The government announced September 3 that it would spend $500 million on new steps to stabilize the plant, including an even bigger project: the construction of a frozen wall to block a flood of groundwater into the contaminated buildings. The government is taking control of the cleanup from the plant's operator, the Tokyo Electric Power Company.

The triple meltdown at Fukushima in 2011 is already considered the world's worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl. The new efforts were developed in response to accidents, miscalculations and delays that have plagued the cleanup effort, leading to the release of enormous quantities of contaminated water.

Analysts are beginning to question whether the government and the plant's operator, known as Tepco, have the expertise to manage such a complex crisis. They say Tepco has resorted to quick, ineffective fixes.

"Japan is clearly living in denial," said Kiyoshi Kurokawa, a medical doctor who led an investigation last year into the causes of the accident. "Water keeps building up inside the plant, and debris keeps piling up outside of it."

Problems at the plant seemed to take a sharp turn for the worse in July with the discovery of leaks of contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean. Tepco announced in August that 270 metric tons of water laced with radioactive strontium, a particle that can be absorbed into human bones, had drained from a faulty tank into the sea.

Contaminated water, used to cool fuel in the plant's three damaged reactors to prevent them from overheating, will continue to be produced in huge quantities until the flow of groundwater into the buildings can be stopped. At the same time, delays and setbacks in the enormous effort to clean up the countryside are further undermining confidence in the government and eroding the public's faith in nuclear power.

The cleanup efforts to date, critics said, were ill-conceived projects begun as a knee-jerk reaction by the government's powerful central ministries to deflect public criticism and to protect the clubby nuclear power industry from oversight by outsiders.

The biggest public criticism has involved the government's decision to leave the cleanup in the hands of Tepco. The recent leaking tank was one of hundreds that have been hastily built to hold the 390,000 metric tons of contaminated water at the plant, and the amount of that water increases at a rate of 390 metric tons per day.

Critics say Japan may be able to come up with better plans if it opens the process to outsiders.

The trade ministry will now take charge of the plant's cleanup. This will include the plan to stop the influx of groundwater into the reactor buildings by sealing them off behind a subterranean wall of ground frozen by liquid coolant.

Some critics have dismissed the "ice wall" as a costly technology that would be vulnerable at the blackout-prone plant because it relies on electricity the way a freezer does.

Nuclear experts also questioned the government's longer-term plan to extract the fuel cores from the reactors, which would eliminate the major source of contamination. Some doubted whether it was even technically feasible to extricate the fuel because of the extent of the damage during the explosions and meltdowns.

Scientists have played down the threat from contaminated water, saying the new leaks are producing small increases in radioactivity in the Fukushima harbor that remain far lower than immediately after the March 2011 crisis.

"This continued leakage is not the scale of what we had originally," said Ken O. Buesseler of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

Perhaps the principal threat of the radioactive water is to the Japanese government. Harutoshi Funabashi of Hosei University said, "Admitting that no one can live near the plant for a generation would open the way for all sorts of probing questions and doubts."

Hisako Ueno, Matthew L. Wald and William J. Broad contributed reporting.

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/15/2013 page11)