Towers of wood, not steel

Updated: 2013-10-20 08:02

By Henry Fountain(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

The movement to construct tall buildings largely with wood as an environmentally friendlier alternative to steel and concrete has received a boost from an unusual source - a leading architectural firm known for its towers of steel and concrete.

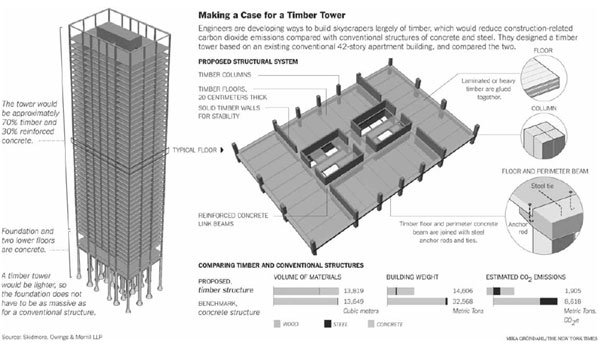

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the Chicago-based firm that has designed a long list of skyscrapers, including the new One World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, has developed a structural system that uses so-called mass timber - columns and thick slabs that are laminated from smaller pieces of wood. In a report this year, the firm showed how the system could be used to build a 42-story residential tower that would have a lower carbon footprint than a conventional structure.

"We wanted to see what we can do to help on the sustainability side," said William F. Baker, a partner in the firm. With its system, about 70 percent of the structural material is wood; most of the rest, including the foundation, is concrete.

Benton Johnson, an engineer who worked on the report, said wooden high-rises could help solve the problem of providing adequate housing to the billions of people living in cities - while also addressing climate change.

"We know that we need to build a lot more buildings," Mr. Johnson said. "And we know that we need to lower CO2."

Until now, tall wooden buildings had been championed by architects and engineers mostly from smaller firms outside the United States. They welcomed the Skidmore, Owings & Merrill report.

Michael Green, an architect in Vancouver, British Columbia, who helped devise a different structural system for wooden towers that was detailed in a report last year, said: "This is the first new way to build in a hundred years. "

Few modern tall wooden buildings have been built around the world, and only one, an apartment building that was completed this year in Melbourne, Australia, has reached 10 stories. Mr. Green's design of a 27-meter mixed-use building in Prince George, British Columbia, will make it the tallest wooden building in North America when it is completed next year.

Constructing more and taller towers will require changes in building codes - most of which limit wood structures to four

stories or fewer - and construction methods. Architects, engineers, contractors and, crucially, developers will have to be convinced that wooden buildings can be safe, attractive and profitable. (They are generally more expensive than conventional towers, although in some areas of construction there can be savings because the slabs can be erected fairly quickly.) Fire protection is a particular concern, but advocates for wooden buildings say mass timber does not ignite easily and forms a layer of char that slows burning. They say wooden towers can meet fire safety standards for steel or concrete buildings.

Production of steel and concrete produces significant amounts of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, while wood holds the carbon from CO2 removed from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. So using wood in the structural elements can help offset the carbon emissions from the other parts of the construction process and from the operation of the finished building. This is not conventional frame construction, in which thin elements are nailed together, but more akin to building with concrete slabs. The use of so much wood raises the issue of the potential impact on forests if wooden buildings were to become prevalent. Mr. Baker said as long as forests were managed, sustainable wooden buildings should not have much of an impact. There are also millions of fir trees in North America that were killed by a beetle infestation and that could be used to produce the timber panels.

The Skidmore, Owings & Merrill system uses a type of engineered wood called glued laminated timber, or glulam, for the building columns, and cross-laminated timber slabs for the central core, floors and shear walls, which provide stiffness against wind loads. But the concept calls for concrete beams along the perimeter of each floor and elsewhere to allow for longer spans and more flexibility in layouts.

Mr. Green, in his report, presents a system that could be used to build towers in seismically active areas like Vancouver. Rather than concrete, he uses some steel beams to allow the building to better respond to earthquake forces.

Andrew Waugh, a British architect whose nine-story apartment building in London, completed in 2009, has become a showpiece of the wooden-tower movement, said both reports would help build momentum for buildings taller than 10 stories.

"It's such an exciting time," Mr. Waugh said. "It feels like the birth of flight - it's one of those kinds of moments in engineering."

The New York Times

(China Daily 10/20/2013 page9)