Prairie storms

|

|

A Mongolian nomad couple and their daughter in front of their yurt in the Dong Ujimqin Banner. Photos by Ayin / For China Daily |

A Mongolian photographer keen to capture the lifestyle of his ancestors, instead finds himself training his lens on a dramatic transformation. Cheng Anqi reports.

Mongolian Ayin, who traces his lineage to Genghis Khan (1162-1227), does more than capture the majestic vastness and breathtaking beauty of the grasslands through his lens. His works are also historical silhouettes of the pastoral nomads.

On a bitter cold winter day in 2007, in the Dong Ujimqin Banner of Xilin Gol League, Inner Mongolia autonomous region, he shot a picture of Urhan, 8, and her father waiting for a school bus next to a dried up river.

He remembered that once this area was verdant grassland.

"When I visited in 1998, there were herds of cattle feeding on the grass."

Since the 1970s, deepening urbanization has brought dramatic changes to the lifestyles of the herdsmen of the Dong Ujimqin grasslands

The Ulagai river, originating in the Greater Hinggan Mountains in Northeast China, once covered a length of 320 km. But by the end of the 1970s, reservoirs built on its upper reaches for fishery left its lower reaches subject to repeated droughts.

The Dong Ujimqin prairie is perched in the hinterland of Inner Mongolia. Till the mid-70s, the Ujimqin tribe had been living there practicing their age-old nomadic ways.

"The neighboring Horqin prairie is the land of my ancestors, but I have no idea how they lived," Ayin says.

The 40-year-old was born into a Mongolian family in Hinggan League but had a settled life and made a living from a photo studio.

In 1998, he moved from Horqin to Dong Ujimqin, "to record the traditional lifestyle of the nomadic Mongolians", Ayin says. Instead, what he saw was a disappearing way of life.

One of his photos shows a herder holding a lamp, sand falling from his fleece coat - a reflection of the desertification of the grasslands.

Violent sandstorms from 1999 to 2001 have destroyed the ecology of the Xilin Gol pastoral lands.

In 2001, 230,000 heads of livestock died in the Dong Ujimqin Banner alone.

With the deterioration of the ecology of the prairie, traditional prairie culture is also vanishing rapidly. Ayin is racing against time to capture what little remains of it with his cameras.

An important celebration for the nomads here is Aobao Festival which falls between May and August of the Chinese lunar calendar.

Aobao means "stone heap" in the Mongolian language. Erected on top of hills, these unique structures have long been regarded as signposts helping people find their way in the vast grasslands. They are also dating places for young people.

The festival goes back to the days of Genghis Khan. The main ritual involves piling stones on an aobao and making offering to it, for good weather and the safety of humans and livestock.

"Within a radius of scores of kilometers from an aobao, it is taboo to dig out any grass or earth, or to slaughter any living thing. These are observed to this day," Ayin says.

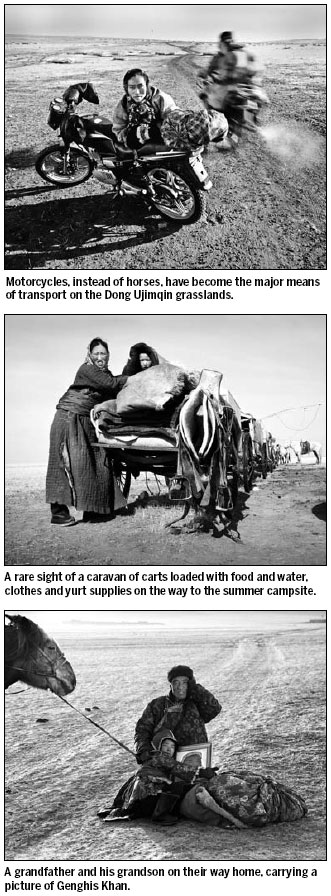

One picture taken in 2007 shows a Mongolian woman moving a caravan of carts to a spring campsite right after the snow has melted.

The cart is loaded with food and water, clothes and yurt supplies.

But after 2007, Ayin says, such sights have become a rarity.

In the past decade, motorcycles have replaced men on horseback in Dong Ujimqin.

"Even the herders ride motorcycles now, where they once used oxcarts."

Shortly after China's economy reform and opening-up in the late-70s, asphalt and concrete appeared through the grasslands.

In the 1980s, the government began to encourage the nomads to live settled lives.

But some of them still pitch their yurts in the open grasslands in the summer. In 2010, Ayin trained his lens on these returning families.

"The settlement is more than 30 km from the pastures. They rent the pastures at 2 yuan ($31 cents) a mu (667 square meters) per year. The grass grows well here in summers, and the nomads move back to their settlement for autumn and winter," he says.

Another picture taken by him shows a Mongolian couple living in a yurt. But three years later, Ayin saw them living in newly built brick house.

The herdsmen know nothing about brick constructions and have to hire others to build their homes. It costs at least 30,000 yuan ($4554) to build a brick house of three rooms. But despite the expense, the herdsmen go for a settled life.

"They have to rent more than 7,000 mu (467 hectares) for their herds every year. They must not only be able to make money out of raising livestock on the limited pastures but also protect these lands," Ayin says.

In 2007, when Ayin shot the picture of little Urhan, her family was still living in a yurt all year round, being one of the few poor families, with only 400 sheep.

Ayin was reminded of his own time in school.

"We would often not be able to afford the tuition. What the school offered was just corn porridge. We felt lucky to be able to eat steamed bread once a week."

Ayin dropped out when he was 14. He studied on his own and eventually embarked on a photography career.

He is passionate about recording the progress in education for children of herdsmen.

The Adiya'eji family, a relatively wealthy one, has always had his attention. Adiya'eji himself did not progress beyond primary school, but is keen his children do better.

They are not only exempted from the tuition fee but also receive an additional subsidy of 420 yuan annually.

In 1998, the Ministry of Education merged schools in pastoral areas into the banner-level schools.

In 2010, when Ayin saw Urhan again, the 12-year-old's family had moved into a bright new house, and she was studying in a Mongolian school of the Dong Ujimqin Banner.

Besides the Mongolian language, her subjects include Chinese, Math, Music, and PE. She hopes to enter college some day and dreams of making it to the stage as a Mongolian singer.