Education a passport to progress

|

|

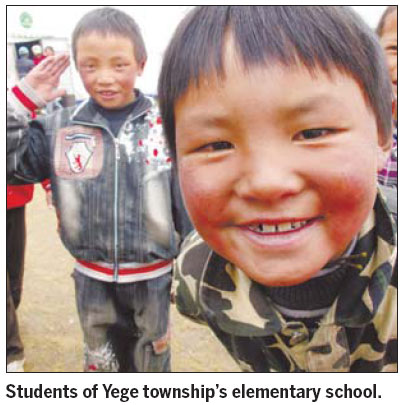

Children play in front of Yege Township Elementary School in Qinghai province's Yushu prefecture. They are the first generation to go to school in this community of about 2,000 nomadic Tibetan yak herders. Photos by Erik Nilsson / China Daily |

|

|

An elderly woman milks a yak in Yege township. Yak dairy is the staple - often, the only food source in this community. |

Nomadic Tibetan yak herders in Qinghai are giving their children the opportunity for learning they never had. Erik Nilsson reports.

Most adults in Yege township don't know numbers, but their children do and they're proud to be different from their parents. The deputy headmaster and math teacher of Yege's primary school, Yongdingquepab, holds up a 100-yuan bill and explains: "If I show this to the parents, they won't know how much it is.

"They don't know if this bill is 5 yuan, 10 yuan, 50 yuan or 100 yuan. If you tell them it's 100 yuan, they don't understand how much 100 is."

But the children know more than just numbers.

As the first generation to go to school in this community of about 2,000 nomadic Tibetan yak herders in Qinghai province's Yushu prefecture, Yege's children can also read and write in Tibetan, Chinese and even some English.

"I'm proud I can read," 12-year-old Renzemdorgyee says, in Mandarin. "Sometimes, other kids will use bad words, and I tell them, 'We're students. We're not like our families'."

Most of Yege's 137 primary school students started school only a few years ago, as their parents previously believed they should herd yaks instead of study.

Consequently, many children are older than usual for their grades. The fourth-grade class, for instance, has two 16-year-olds.

Yongdingquepab says he and the other teachers traveled from tent to tent over hundreds of kilometers to explain the value of education to the families in 2005.

He would show them the 100-yuan bill and a bottle of iced tea and ask them what he was holding.

"When the parents couldn't tell how much money was on the banknote or identify what liquid was in the container, I asked them, 'Do you want your children to be able to?'"

It worked. All of the families agreed to send their children to school.

English teacher Tseringbum says the instructors, in turn, learned a lot from the parents.

"They told us we should make school more fun for the kids," he says.

Kangia, chief of Yege's Hongqi village, says it is important to keep pace with development.

"People without education can't use mobile phones, and if they go to a shop, they don't know that a drink is a drink," he says.

Kangia speaks the Khams Tibetan dialect and a "tiny bit" of Qinghai dialect.

"We want more help from the government and foundations but can't communicate well enough to ask for it," Kangia says.

More than 60 percent of Yege's residents survive on between 300 yuan ($47) and 1,500 yuan a year. The average annual income hovers around 2,000 yuan, he says. There are few prospects for Yege's uneducated adults to overcome the poverty exacerbated by harsh natural conditions.

"Our people don't try their luck as migrant workers, because they say they don't know how to do anything other than raise yaks," Tseringbum says. "They don't know how to construct buildings or sew textiles. They can't communicate with outsiders."

But as more adults believe in the value of education, many have started taking literacy classes, which began in 2005.

And a growing number of families are building houses near the school, which has become the "absolute center" of the town geographically and civically, residents say.

"When the school needs to do something, like pitch a tent, most parents help," Yongdingquepab says. "Before, they expected the teachers to do everything."

However, the school's rise to prominence in local life was slow, not only for the parents but also for the children. Yongdingquepab recalls three boys ran away during their first week at school. He and another teacher went looking for them on a motorcycle. When the bike broke down, they wandered to a nearby house and asked to borrow horses.

"We found them alone in their parents' house," Yongdingquepab recalls.

The teachers had to coax them back to the school by playing games with them and offering them food, he says.

"On the road, they saw a bear. The kids said they were scared and wouldn't run away again."

Yege's children eventually adapted to school life and stopped running away, he says.

"The kids came to love studying over time," Yongdingquepab says. "And the parents feel relieved, because the school provides food, clothes and education."

That education, in turn, offers Yege's students futures unimaginable to their parents. Many want to work in medicine.

"We're short of doctors," Yongdingquepab says. But few families can afford to send their children to university, he adds.

"If they can't make it to university, they want to do business," he says.

"Three students say they want to open a market and sell fruit in Yege. There's no place like that here now. The children want to help Yege develop."

Other students want to become teachers, Yongdingquepab says.

"Our hope for them is they will return to teach the younger students."

Renzemdorgyee, the fourth grader, has made this hope his own.

"If I can be a teacher," he says, "I can help more people learn how to read. Their lives will be better."