Shaping concepts

|

|

Chen Xuebo shows off his sculptures of heroes from various periods in his studio courtyard in Haikou, Hainan province. Photos by Huang Yiming / China Daily |

|

|

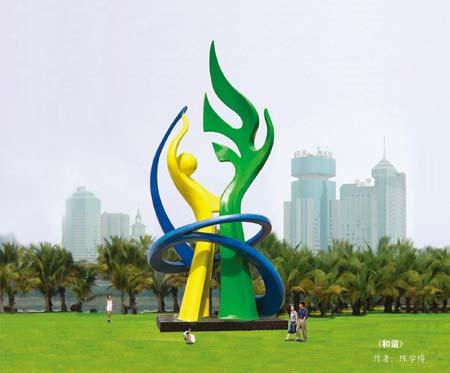

Harmony is Chen Xuebo's interpretation of Hainan Island with its sunny weather and blue sea, and, most importantly, how humans should relate to the environment. |

A Guangzhou-trained and London-reinforced sculptor is blazing a trail in coconut palm trees-dotted Hainan, Raymond Zhou and Huang Yiming report in Haikou.

When Chen Xuebo was a child, he stumbled upon piles of plastic discarded from his father's factory that his dad had taken home to mend. In the father's absence, Xuebo attempted to make something out of them. His dad found out and, instead of scolding the youngster, encouraged him to develop an interest in sculpture.

Now, at 38, Chen Xuebo might be the most celebrated sculptor in Hainan province.

And his father, now retired, takes charge of miscellaneous tasks in the son's studio, which employs seven to eight people, many of whom are fresh graduates from fine arts schools.

On an early March morning, he was showing off an elaborately carved wood stand that supports a pair of giant clamshells. It was a present from the Hainan delegation to the National People's Congress during its annual session.

Dad was making a final round of examination before packing it up and shipping it to Beijing.

Chen's exuberance for youthful memories is evident in an installation piece called Childhood, which uses chicken wire to create a half vanished rendering of two kids. Inside their upper bodies are origami-like bits of paper, highly reminiscent of student years.

The piece is among the few dozen of his works on display in a park along a major boulevard in Hainan's capital Haikou, overlooking the straits from the mainland.

Since 2007, Chen Xuebo's sculpture has been a centerpiece of the Spring Festival exhibition that runs for more than a month and attracts millions of visitors.

"This open space used to host a lantern show. But what's so unique about red lanterns in Hainan? We need more cultural exhibits to bring up the level of artistic appreciation for our people," he expounds.

Chen believes it's less likely for a random sightseer to walk past a statue in Hainan than anywhere else in China. But he is determined to change that.

"When people think about a place, a statue could be the first thing that comes to mind," he says.

"Talk about New York and people conjure up thoughts of the Statue of Liberty. Copenhagen has its Little Mermaid. Brussels' Peeing Boy embodies some of its history. And the Five Rams stone carving tells the origin story of Guangzhou city. The public sculptures have become these cities' landmarks."

Chen had a chance to distill his vision of his hometown into a showcase that would stand in front of a major government building.

Harmony is a 6-meter-high abstract piece made of stainless steel, with a yellow human figure seemingly saluting a green part that could be a flying bird or a palm tree. The blue ribbon floating around them represents the sea, he explains.

His design was vetted by numerous rounds of public feedback and approved by the authorities.

Right before it was installed, a change of government leadership sidelined the project. Now, this elegant yet vibrant piece that embodies so many crucial elements of the island stands on the lawn of a local school.

Chen believes public art like sculptures should be an integral part of public spaces.

"If you put something in after it's well built, it may not fit the site," he says.

"You can plan it without commissioning the sculpture if funds are not sufficient."

As for whether a piece can be a landmark, he says: "That is up to all the people of a city to decide, and only time can tell."

Meanwhile, he is working on many government projects that require a solid Realistic technique and a familiarity with revolutionary fine arts traditions.

On a wall in his studio courtyard is a procession of busts of revolutionary luminaries, such as Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai.

"Some of these were from my student era," he says.

Standing around are smaller models of heroes from various periods in typical heroic postures.

"They are not of the uniform Soviet style, even though it heavily influenced a whole generation of artists of New China," he explains. "But I must take clients' preferences into account."

Chen surmises the US commissioned Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin to create a statue of Martin Luther King, partly because Chinese artists are known for their training in Realism and heroic portrayals.

However, Chen isn't satisfied with repeating what others have done.

He is always looking for something fresh to inject into his art. Even his Buddhist statues have a subtle verisimilitude that set them apart from the ubiquitous ones that adorn the country's temples.

"Look at this duo of stone lions," he says, pointing to his studio's gate.

"The stone lion business is monopolized by stone smiths from Fujian province who pass the skill from generation to generation and charge 25,000 yuan ($3,970) for a pair. But mine is nothing like that. It is an African lion and costs 100,000 yuan more than the regular one."

That's the premium one pays for art over craft. But is Hainan ready for it?

Chen received his formal education at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and honed his skills in the 1990s in the coastal boomtown where real estate developers jumped into the craze of copying classical European sculptures.

"It was not artistic creation, but it helped solidify my creative foundation," he says, as he shows a smaller replica of Michelangelo's David.

In 2000, Chen decided to move back to Haikou, where he was born and raised, in hopes of starting his own business.

He scraped together 100,000 yuan from his family, but things did not start smoothly.

A place he rented and renovated at great expense was suddenly marked for demolition.

At the most difficult point, his first commission came - from as far as Shanghai, for a series of works for an Olympic park.

Since then, he has had no fear of running out of work.

An annual average of a dozen pieces are requested, "many by schools who want a more artistic environment for their students".

Chen had always wanted to finish graduate studies but failed the English-language test.

Undaunted, he took on the task that had defied many a Chinese artist. After passing language eligibility, he enrolled in London-based Middlesex University and graduated in 2009 with a Master of Arts.

"I learned abroad that art is diverse," he says.

"Every sculptor should be unique."

He was invited to the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai for an exhibition where some of his more avant-garde pieces met with very positive reception from the viewing public.

"People participated in the installations and their curiosity was piqued," he says.

Chen figures he must "walk on two legs", meaning he'll continue to resort to Realism for most public projects and reserve his experimental streak for his private consumption, until the public is "more open-minded toward art".

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.