Roller coasters for purists

|

|

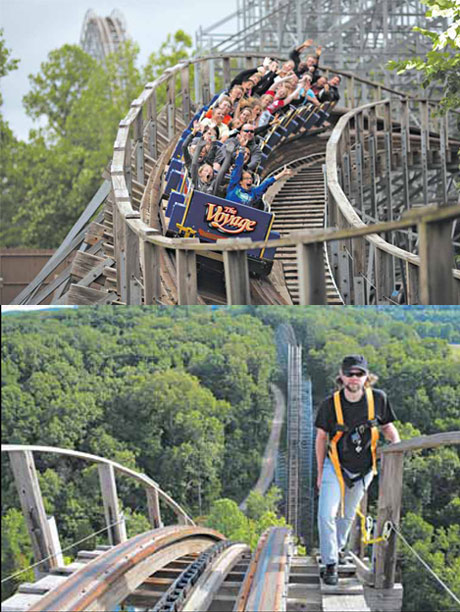

Chad Miller, left, of the Gravity Group, one of a dozen companies that design roller coasters. The Voyage, above, the world's second-longest wooden coaster, has a steel support structure. Fred R. Conrad / The New York Times |

New wooden structures cater to demanding fans

SANTA CLAUS, Indiana

From the summit of the wooden roller coaster called the Voyage, 50 meters above the Holiday World theme park in southern Indiana, the track drops 47 meters at a 66-degree angle. The cars quickly reach a top speed of nearly 112 kilometers an hour.

Those gasp-inducing numbers help explain why more than a million people a year visit Holiday World, and why the Voyage earns high marks from connoisseurs.

New wooden coasters are relatively rare, as steel-rail designs are generally faster and higher (and less expensive to maintain) and have more nausea-producing features like barrel rolls and corkscrew loops. But the Gravity Group, which designed the Voyage, has a coaster in Sweden that opened last year and has undertaken several projects in China, where the growing middle class has fallen for amusement parks.

"The secret of the first drop is shaping up that parabola and getting it exactly right," said Chad Miller, 38, an owner of the Cincinnati-based Gravity Group, one of about a dozen coaster design firms in the world. "It gives you just the right amount of air time, especially in the back seat."

"Air time" is coaster vernacular for negative g-forces that lift the rider out of the seat, and results from changes in the car's speed. Along its 1.9 kilometers - it's the second-longest wooden coaster in the world - the Voyage has steep drops and tight curves that affect speed, making for 24 seconds of air time, an unofficial record.

In designing coasters, the first priority is to make riders safe; the second is to make them scream.

Mr. Miller and his three partners work the numbers carefully, using their own programs. At regular intervals along the route, the software calculates g-forces on riders in the front, middle or back of the car.

The designers stay well within g-force limits established by the standards organization ASTM International. But their goal is to shake riders up.

The track on the Voyage twists and turns (one section is called the spaghetti bowl), banks up to 90 degrees, weaves in and out of the supporting structure and dips through tunnels and under beams (called "head choppers" ).

Of the track's nearly 2,000 meters, Mr. Miller said, "We had so much track to work with, we said, 'Let's do some really cool stuff.'"

Wooden coasters have rails made from laminated pressure-treated pine, laid on wooden boards called ledgers, with only thin ribbons of steel where the car wheels make contact. Purists say the supporting structure must be of wood, too, but the Voyage is one of many with steel supports.

The Voyage, built in 2006 at a cost of $9.5 million, is consistently ranked among the top wooden coasters in the world.

"It's the best I've ever ridden," said Sister Michelle Sinkhorn, a Benedictine nun who lives nearby and says she's done it at least 100 times. She keeps her hands up the whole time: 2 minutes and 45 seconds. "I'm a free flyer," she said.

Byron Hughes, a retiree from Birmingham, Alabama, said: "I like the out-of-control feeling."

That sensation doesn't happen by chance. Because wooden coasters tend to be slower, they can have tighter twists and turns than steel ones without generating excessive g-forces on riders.

One way to think about air time, Mr. Miller said, is to imagine the trajectory of the car coming over a hill. If the track is designed so the car's trajectory is slightly lower than that of the riders, the riders will experience air time. It's not so much that the passengers go up, but that the car (which has safety wheels under the track) goes down. "Essentially the track is leaving you," Mr. Miller said.

Coaster designers are constrained by the amount of potential energy they have to work with, which is determined by the weight of the car and its riders, height and gravity. It is highest at the top of the first hill. As the car coasts down the hill and up the next one, friction takes its toll. The amount of potential energy declines along the route, and no other hill can be as high as the first.

Mr. Miller said the designers do not have to be very specific about energy losses along the route. "Wood is a very imprecise material," he said. "If it's cold, then you are going to have one amount of friction loss. If it's hot and just rained, mixed with the oil on the track, it's going to fly like crazy."

They design the ride to generate forces that are well under ASTM limits (which take into account magnitude, duration and direction), because of this weather effect and because of concerns about maintenance. Far more than steel, wooden coasters can get rougher over time. Sometimes a complete overhaul is needed.

When Holiday World decided last year that a run of track in the spaghetti bowl was too harsh on riders, the Gravity Group redesigned it with a gentler alignment. Sister Michelle was alarmed when she saw a photo on Facebook with the section ripped out.

"I thought, 'What's that really going to do?'" she said. "But when I rode it a few weeks ago, it was as smooth as a baby's bum."

The New York Times