Black is losing its luster

The bumpy mountain path and complicated mountain topographies are natural barriers against not only chaos of wars in the past, but also prosperity of modern society today.

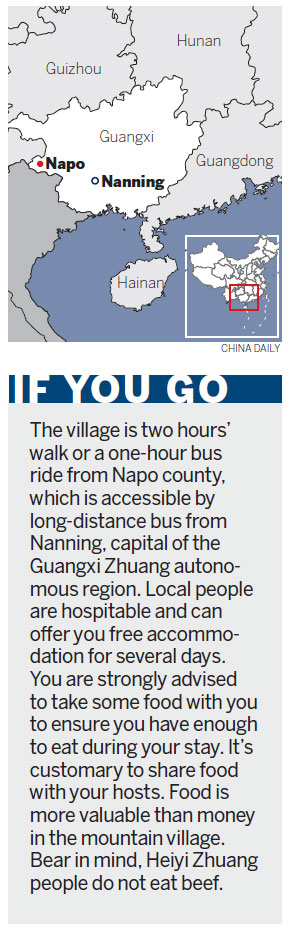

The villagers' ancestors fled to the small basin along the Youjiang River valley from Nanning, capital of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The only access to Dawen is a steep gravel mountain path over a cliff.

|

|

Residents of the village are mainly elderly, women and children. |

The village's square is a basketball court with rusty stands, now used as clothes driers. On one side of the court is a clinic and a large yard partly enclosed by three two-story wooden buildings.

According to Liang Jincai, the gatekeeper of the yard, this is a museum sponsored by a joint program of Chinese and Norwegian governments.

The museum was constructed in 2008 by villagers of Dawen. Most exhibits were contributed by the villagers, including articles of daily use.

Liang, 75, a retired village head, works in the museum as the only attendant.

He is also the ritual leader. But his role is diminishing.

"Villagers invite me to conduct religious rites and chant sutras only when there is death in the family. Although my elder son will take over my position, I don't think the family honor will pass down to my grandson," he says.

"All my four daughters and two sons are in Guangdong, like the other young people in the village. They only come home during the Spring Festival."

|

|

Many Heiyi Zhuang people still carry on the tradition of wearing black clothes in Napo county, Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. Huo Yan / China Daily |

His concern is not groundless.

A third of the old houses have been replaced by new buildings, using the money sent by the young people working in the cities.

Those who still live in the village are mostly women, children and elderly people.

The residential adobe buildings are usually three-story and built with wood, mud and self-made black pottery tiles.

The first floor is used to raise cattle, pigs, chickens and ducks. The second floor is made up of two to three bedrooms, a dining room and a kitchen with a small family ancestral temple room in the middle. The third floor is the attic for storing grains, seeds and food.

"We used to make almost everything we need - cloth, food, wine, furniture, soap, everything. We raised cattle to cultivate land, pigs to generate fertilizer, chickens and ducks in exchange for salt in a local bazaar," says 42-year-old Ma Qingjing.

Her husband works as a construction worker in Guangdong, while she takes care of their two children, parents and two patches of corn field in the mountains.

"The young people no longer believe in gods - in stones, rivers, mountains, soil, cattle - as much as we do. I don't blame them. I suppose to them, money, knowledge and cities are their gods. Our songs, dances, languages and sutras will be lost one day as they lead a different lifestyle," Liang says.

Another dying custom is the old funeral rites.

According to the traditional rites, the family should dig out the bones of dead people three years after burying them and wash the bones piece by piece, put them in a porcelain pot and bury the pot in a new place. The grave should be covered by rows of tiles.

This is also one big concern for Liang. "I hope I can be buried like in the olden days. Otherwise, I won't be able to enjoy a peaceful life in the other world."