View

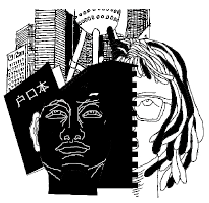

Shanghai turning its back on the poor

By CHEN WEIHUA

Updated: 2009-06-29 00:00

|

Large Medium Small |

Two new regulations made public in Shanghai last week could be best interpreted as an effort to make the country’s biggest metropolis less welcome to the underprivileged and less affluent.

The draft law on group rental housing, posted online by the government for public deliberation, requires each tenant to have a minimum living space of 7 sq m. If passed and enforced, it would render many migrant workers and recent college graduates homeless.

The government argument — to reduce safety and health hazards in group rental accommodations and ease complaints from neighbors — seems to be based on good rationale. Yet, by resorting to a total ban, it disregards the dire economic situation of those cramped up in group rental apartments, where two bedrooms are often divided into six or more sections.

How can this low-income group afford bigger living spaces in Shanghai, one of the most expensive cities in Asia? The government is yet to address the question.

It is unfair to make life tougher for the already struggling underprivileged.

The right approach is to adopt a more balanced approach, such as urging fire departments to go to the communities and promote safety measures, or building more affordable apartments for low-income individuals.

Those who drafted the regulation clearly suffer from a memory deficiency. Just in 1985, the average per capita living space in the city was only 4.4 sq m. It jumped to 6.9 sq m in 1992. Though that figure has since soared to about 20 sq m, many Shanghainese living in old neighborhoods still squeeze in crowded homes.

On Wednesday last week, the government announced another rule that would break the hearts of many migrant workers in town. The detailed measures to switch temporary residency permits to permanent ones almost exclude an estimated 5-to-6 million migrant workers in Shanghai from getting a local hukou, permanent residence permit.

You will forever be treated as a migrant worker even if you have lived in the city and paid taxes for decades. The door is open only to the rich and educated.

In fact, the two regulations are making the city less friendly to the poor. For example, Shanghai has banned street artists performing in subway stations, without banning those annoying sports cars from booming in the city center. The city is also driving away vendors from street corners, while turning the limited public space in our communities into car parks.

District governments have also evicted many popular and affordable stores on the city’s two major shopping streets on Huaihai and Nanjing roads. Only luxury brands such as Rolex and Gucci are welcome. Historic buildings on the Bund also house only classy stores such as Giorgio Armani and big-ticket restaurants like Laris, instead of museums that the general public can frequent.

The message to the poor and underprivileged or even many ordinary residents is clear: You don’t belong here. More and more poor and underprivileged in Shanghai are getting the hint that they don’t belong to the city. When their downtown houses are torn down, the only places they can afford are near the suburbs. Roads in Shanghai, meanwhile, are also designed to favor the affluent car owners rather than the bikers.

Lawmakers and government officials always seem to have the rich and powerful in mind when making rules. They seem to have not taken the poor and underprivileged into consideration.

Simply put, this is against the principle of either a socialist country or a harmonious society. Our laws should be made to work for the poor and the underprivileged, not against them.

chenweihua@chinadaily.com.cn