Latest News

Saved in one swoop

By Chen Liang (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-01 07:31

|

Large Medium Small |

|

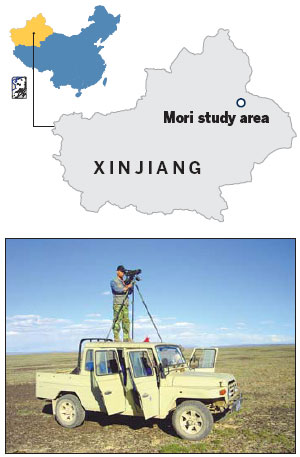

A houbara bustard on the arid steppe of Mori county, Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. [Photo/China Daily] |

|

Yang Weikang looking for the houbara bustard atop a jeep at the Mori study area.[Photo/China Daily] |

|

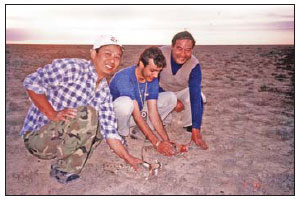

Yang (left), his colleague and a UAE scientist (middle) prepare to release two houbaras banded with transmitters at Mori.[Photo/China Daily] |

The Asian houbara bustard is at grave risk of extinction. But help is now coming from countries whose ancient hunting traditions pose a major threat to this shy bird. Chen Liang reports

Few Chinese have heard of the houbara bustard, fewer still have seen the bird in the wild. Nesting in the open deserts and arid steppes of Northwest and Northern China's Gansu province, and the Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous regions, it is a crane-like bird with a sandy buff plumage, mottled with dark-brown spots. Very shy and cunning, it can spot threats from hundreds of meters away, thanks to its superb vision.

But neither the houbara's guile and adaptation to marginal lands inhospitable to human beings, nor the nation's first-level protection are enough to save it from extinction.

This is a migratory bird and while flocking to Iran, the Arabian Peninsula, Afghanistan and Pakistan en route Central Asia for the winter, it faces its major threat - hunting.

The houbara is widely prized in the Arab world as an ultimate prey for falconers. Falconry, an Arab tradition from ancient times, has seen a resurgence recently with the growing affluence of the oil-producing nations.

"It was a way to make a living on the Arabian Peninsula," Dr Yang Weikang, an ecologist with the Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography (XIEG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, tells China Daily at his office in Urumqi.

"Now it's a high-tech sport, complete with GPS and four-wheel drives."

Besides hunting, the extension of agricultural lands and overgrazing have led to destruction of the houbara habitat and are important factors in the shrinking of the bird's Asian population - the largest of which stands at between 39,000 and 52,000.

"While the relative importance of these factors is not yet clear," Yang says, "the loss of habitat has affected the bird's population both on its breeding and wintering grounds, and on its migration routes."

International cooperation on research on the houbara and its conservation is the only way to save the bird, he says.

Since 1997, the institute has joined hands with the National Avian Research Center (NARC) in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, for research on the houbara and its protection.

With financial and technical support from the center, XIEG's researchers have now determined the bird's distribution, migration routes and breeding grounds, made an estimate of its population, unraveled the mysteries surrounding its breeding and identified the main threats to its survival.

These have been published in the 2009 book titled, Houbara Bustard in China.

More importantly, the researchers have managed to put the bird's most important breeding site under protection.

"We are now able to keep a close eye on the area with the largest concentration of the houbara and their breeding sites," Yang says.

Covering more than 3,000 sq km, the area is a stretch of desolate rangeland in Mori county of eastern Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

Studying the houbara since 1996, Yang says the Mori population has shrunk from an estimated 200 birds in 1998 to about 50 at present. But still, "it is the best place to see the bird in the country", he says.

He estimates there are still about 2,000 bustards breeding in China.

The decline began in 2000, when Kazakhstan welcomed wealthy Arabian falconers from the Gulf to bag houbaras. Kazakhstan is not only the bird's largest breeding ground, but also lies on its migratory route.

"This means that hunting of the houbara has spread from its wintering habitats to its migratory routes and breeding grounds," Yang says. "The implication of this is that many of our bustards may never make it back the next spring."

The increasing threat of extinction of the Asian houbara has pushed countries such as the UAE to work on conservation.

The cooperation between XIEG and NARC began in 1997. Under a three-year project, scientists from both sides made a nationwide survey about the bird's population and distribution and found the Mori study area, building a research station there in 1999.

Yang and his colleagues have been studying these birds ever since they moved into the station in 2000.

They found that after leaving Mori, some of the young birds would join the breeding flocks in other areas the next year. "That means possible gene exchange between different breeding groups," Yang says.

The houbaras typically lay eggs twice during their breeding season between mid-April and July. In Mori, Yang and his colleagues once even found a record six eggs in a houbara nest, which typically have three or four.

Since 2008, Yang and his team have launched another project to survey and monitor the houbaras in the country with $500,000 from UAE. Under the project, they will make two regular surveys a year at the Mori site till 2012.

In spring and early autumn, they will go to Mori, count the birds, record the numbers of their predators like foxes and buzzards and observe the changing of their habitats.

"Such data is important, especially in the light of joint cooperation by China and UAE to build a breeding center in Mori," Yang says. "With the hunting tradition deeply rooted in Arab culture, UAE's investment in captive breeding is certainly a big step in the protection of the houbara and the restoration of its numbers."

According to the ecologist, NARC started breeding attempts in 1993 with donated birds. It was aimed at re-stocking the depleted populations for hunting and falcon training.

Between 2006 and 2007, UAE invested in and built a large breeding center in Kazakhstan.

The numbers of the bird in China is one of the healthiest, with the highest average number of eggs at a nest - 3.8 eggs - and the longest migratory route - up to 7,000 km.

But the overgrazing, mining and fencing of steppes have destroyed the birds' habitats in the country.

"Even though a breeding center would certainly help restore numbers, you need to find enough habitats to re-introduce them in the wild," Yang says.