View

Entering a Chinese zeitgeist

By David Gosset (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-31 08:13

|

Large Medium Small |

In viewing a traditional Chinese painting, the eyes do not have to follow a linear perspective from a fixed and external position to a vanishing point; they move within a scroll and, like a movie camera, capture a shifting focus. In a sense, the connoisseur is not facing a representation that has to be interpreted but enters a scene, a landscape or even a mood animated by a fundamental energy, the qi, which has to be appreciated. Similarly, in order to comprehend China's dynamics, one should not be concerned by theoretical constructions or grand systematic designs. Instead, one should try to empathize with an experience.

China's praxis can baffle an analyst, but in a time of permanent crises when the ability to constantly unlearn, rethink and redefine is required, the Chinese mode of action is more conducive to success than the strict implementation of any hypothetical Chinese model. Laozi's Tao Te Ching already prepared the Chinese mind to a world of paradoxes: "The sage relying on actionless activity (wu wei) carries on wordless teaching."

Following Deng Xiaoping's policy of opening-up, the increasing economic, political and cultural weight of China in world affairs is widely recognized as one of the main features of our times. According to the Global Language Monitor, an organization which tracks trends in word usage, "the emergence of China" has been the top story of the last decade.

As a result of China's re-emergence, some elements of Chinese culture are becoming more visible - gradual increase of Beijing's soft power - but what is more significant is the objective correspondence between the fluidity of the Chinese worldview and a new air du temps - the making of a Chinese zeitgeist.

The co-existence of a gigantic bureaucratic state with an overall social elasticity and transformation whose scale has no equivalent in world history is an apparent paradox that puzzles the observer of Chinese society. Why is China so comfortable with change while Western democracies are dangerously lacking in the capacity to question their assumptions and could, in the long term, be threatened by inertia and complacency?

As the Chinese renaissance gradually reshapes the 21st century and takes the global system to another level, understanding China has become a practical necessity.

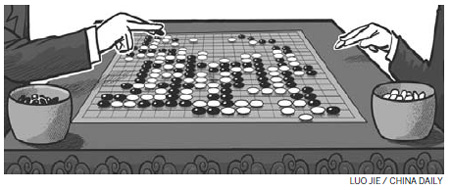

By considering the weiqi board game (known in the West by its Japanese name of go), one of the most significant symbols in the Chinese mental geography, one can develop a better understanding of Chinese dynamics in politics, in business, and even in more trivial social interactions. The tao of weiqi envelops an aesthetic and an intellectual experience that takes us closer to Chinese psychology and gives us insights into Chinese strategic thinking. It is also, to a certain extent, a way to approach the fundamental patterns of China's collective success.

In imperial China, weiqi had the status of an art whose practice had educational, moral and intellectual purposes. In a Chinese version of the scholastic quadrivium, the mandarins had to master four arts, known as qin, qi, shu and hua. It was expected of the gentlemen to be able to play the guqin (qin), a seven-stringed zither, and also to write calligraphy (shu) and demonstrate their talent at brush painting (hua).

The second artistic skill, qi, is a reference to weiqi, a strategy game played by two individuals who alternately place black and white stones on the vacant intersections of a grid. The winner is the one who can control, after a series of encirclements, more space than his opponent. One can translate weiqi as "the board game of encirclement" . For centuries, literati have been fascinated by the contrast between the extreme simplicity of the rules and the almost infinite combinations allowed by their execution.

Traditionally, the game was conceptualized in relation to a vision of the world. In the early 11th-century, Classic of Weiqi in Thirteen Sections, arguably the most remarkable essay on the topic, the author uses notions of Chinese philosophy to introduce the game's material objects: The stones "are divided between black and white, on the yin-yang model the board is a square and tranquil, the pieces are round and active".

As indicated in the introduction of the Classic of Weiqi, the tao of weiqi cannot be separated from Sun Tzu's Art of War, which has stood since the Warring States Period (475-221BC) as the very foundation of China's strategic thinking.

While in chess or in Chinese chess (xiangqi) the pieces, with a certain preordained constraint of movement, are on the board when the game begins, the grid is empty at the opening of the weiqi game. During a chess game, one subtracts pieces; in weiqi, one adds stones to the surface of the board. In the Classic of Weiqi, the author remarks: "Since ancient times, one has never seen two identical weiqi games."

Three golden axioms expressed in the Classic of Weiqi give a stimulating perspective on China's strategic thinking and also on the Chinese mind. "As the best victory is gained without a fight, so the excellent position is one which does not cause conflict," says the Classic.

It introduces what can be called the axiom of non-confrontation. In weiqi, the objective is not to checkmate the opponent: Only positions in relation to others really matter. Weiqi's innumerable circumambulations aim at increasing influence without reducing the opponent's forces to nothing. The ability to manage the paradox of a non-confrontational opposition requires the highest emotional and intellectual qualities.

The Classic adds: "At the beginning of the game, the pieces are moved in a regular and orthodox way, but creativity is needed to win the game." What can be called the axiom of discontinuity is a variation on a postulate that is central to Art of War: At the beginning of the engagement, the action is guided by accepted rules, but victory often requires "irregular" decisions or unorthodox resolution, and only visionary intuition leads to breakthrough.

The notion that an unimaginative China would be destined to repeat, imitate or perform mechanically is a misconception largely based on a partial knowledge of the Chinese world but which, despite the admirable research of British Sinologist Joseph Needham in Science and Civilization in China, persists to distort the debate.

The postulate of discontinuity is the very essence of innovation. To a certain extent, Deng Xiaoping's extraordinary concept of "one country, two systems" to realize Hong Kong's reunion with the motherland was an application of this second postulate. Chinese leaders from Beijing and Taipei will also make full use of the second axiom to reinvent their relations in the coming years.

The authors of China: The Next Science Superpower? (2007) affirm: "China is at an early stage in the most ambitious program of research investment since John F. Kennedy embarked on the moon race." The country will not only innovate in technology (more than half of telecom equipment giant Huawei's 60,000 employees work in R&D) but will also contribute to the metamorphosis of the creative industries.

Incubator of scientific innovations and creative, China will also enrich the vocabulary of social sciences through research developed in think tanks which have now the financial means to attract world-class academics. Western political, business and opinion leaders have to be ready to act in a world with material or immaterial products not only "made in China", but also created and conceived by China.

The Classic mentions a third dimension: "Do not necessarily stick to a plan, change it according to the moment." The axiom of change commands the player to adjust to the situation and to beware of blind adherence to a preconceived system, doctrine or ideology. Deng Xiaoping's emphasis on the necessity to "seek the truth from the facts" profoundly continues this pattern of Chinese strategic thinking. At the diplomatic level, Mao Zedong's unexpected rapprochement with Washington in the 1970s was in the spirit of the third postulate.

These minimalist axioms connect China's tradition with the global village. Today, as interdependence grows, actors are simultaneously partners and competitors in various forms of non-confrontational opposition, and amid changes and crises, a capacity to unlearn and rethink is more useful than the application of established intellectual constructions. Definite principles generate comfort but are limiting; in chaotic times, minimalist postulates constitute the most effective intellectual compass.

Laozi suggested 2,500 years ago that "the highest good is like that of water", and explained that "nothing under heaven is softer or more yielding than water" even if "one cannot alter it". Softer than Joseph Nye's soft power, the Chinese mind is in its element in the 21st century.

The author is director of the Euro-China Center for International and Business Relations at China Europe International Business School, Shanghai and Beijing,and founder of Euro-China Forum.