Slowing globalization 'presents many challenges'

|

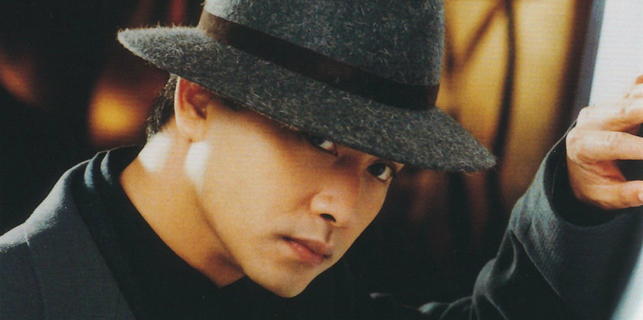

Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times, says the protectionist and isolationist measures espoused by US President Donald Trump pose a major threat to the established global trading order. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

China needs to encourage others to keep their markets open and open its own market further, Financial Times commentator says

Martin Wolf believes globalization - which has been partly driven by the emergence of China as a major economic power - is now in crisis.

The economics writer says the protectionist and isolationist measures espoused by US President Donald Trump pose a major threat to the established global trading order.

"I don't like using the word crisis without some provocation but I think it is pretty clearly in crisis for essentially political reasons but ones which, of course, have economic roots.

"I wouldn't have felt that a year ago, although there were clearly risks. but now that is a fair judgment."

Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times, was speaking in his suite at the St. Regis Hotel in Beijing ahead of the 18th China Development Forum, where he was a panelist.

The 70-year-old, who has many followers in China (his newspaper also publish a Chinese edition), says the trend away from globalization presents many challenges, not least to the world's second-largest economy.

President Xi Jinping made a rigorous defense of the existing order in his speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January.

"It obviously raises profound questions for countries whose prosperity has been built to a certain extent on exploiting trade opportunities, as President Xi pointed out," he says.

"China needs to encourage others to keep their markets open and, if possible, open its own market further so it creates the opportunity to serve this mass consumer market, which will become a new pole for global trade, and which historically the US has been."

Wolf says that Donald Trump's combination of protectionist and bilateralist policies were unprecedented.

"It would be an exaggeration to describe them as an articulated and coherent policy, and it is unclear how that combination of policy impulses will actually work," he says.

"The only real precedents are how the economy was run under the Nazis in the 1930s and how Europe was managed immediately after World War II when there was a series of agreements on bilateral trade that had a strong protectionist core. In normal non-crisis times, their combination is rather novel."

Wolf says there is, however, evidence already of globalization in decline, with trade as a proportion of global GDP stagnating.

"It is growing nothing like as fast as it used to be. Trade is the bedrock of globalization. It is not the biggest financial flow but it drives foreign direct investment, and without international trade it is not clear what trade in financial assets would be for, because ultimately financial assets are just claims on future goods and services," he says.

He says the original impetus for globalization came with the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in the late 1940s and liberalizing measures which came from both the Uruguay Round of talks in the 1980s and 1990s, and then China's accession to the World Trade Organization (the successor to GATT) in 2001.

"The cessation of major liberalization efforts has been one of the reasons for the slowdown in trade. The problem we have now is that the United States, which was the original promoter of the whole system, is led by an administration that opposes most of the assumptions on which it was built."

Wolf, however, believes that if the new US president carries out his threat to impose trade sanctions against China - such as a 45 percent tariff on imports - then Beijing should refer the matter to the WTO.

"If the US acts in a way that is incompatible with those norms, then China would have no alternative but to take the US to the WTO, and I would expect it to find in its favor."

Wolf began his career with the World Bank in the 1970s as an economist, before eventually joining the Financial Times 30 years ago.

He is not someone who has been afraid to shift his position. He was an exponent of the free market economic policies pursued by Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US from the 1980s onward.

After the global financial crisis, however, he has been a pivotal figure in the resurgence of Keynesianism and seeing a new role for the state in economic management.

He questioned the over-reliance on a blind faith in market liberalism in his 2014 critically acclaimed book, The Shifts and the Shocks, which is now published in Chinese.

He is pessimistic about the developed world, in particular, returning to what would have seemed normal economic activity before the global financial crisis.

"I think we are stuck in this position for a long time, and plausibly it is going to get worse because of the demographic trends (fewer people of working age) and because productivity growth is weak.

"The fiscal pressures in this environment are permanent and a constant worry. Inequality seems likely to rise, and we don't really know in the developed world how to generate high-quality jobs for the majority of the population. You have in addition the whole robot problem which has already begun in many ways."

He says this is unfortunately set against a population that demands an ever-higher standard of living.

"Economies are finding it increasingly difficult to deliver this, and it has led to all the political stresses we now have."

Wolf, however, does not expect any sudden contraction of growth in China despite the higher and escalating debt levels that concern some economists.

"I think they can avoid it over the next few years because they can always create more credit. As long as they create more credit and people hold it willingly, they can always finance the investment that will generate more output.

"The only problem is that it could make the ultimate disequilibrium bigger. But I think the risk of a bigger hangover from this lies in the 2020s and not next year."

Although China has contributed around 25 percent of all global growth since the financial crisis, he does not believe the growth of the rest of the world is as reliant on China as it has been.

"Since about 2012 the growth of net imports into China has been very slow and so, therefore, has the demand stimulus from China to the rest of the world. The main beneficiary of China's growth is by and large China itself."

He believes, however, that the government is following the right course of action in gradually opening up its financial markets and dismissed any suggestion they could be substantially or fully open by 2020, as some have forecast.

"If it was to suddenly liberalize its capital account, there is a risk this would be wildly destabilizing. There could be a sudden giant outflow from China depressing the exchange rate. I think if we have full liberalization of the capital account by even 2030 that would be extraordinary, and I would be surprised if it were even that soon."

Wolf - like his newspaper - was a firm advocate of the UK remaining in the EU in last year's referendum and he remains depressed about the outcome and the two years of negotiations ahead after Article 50 of the EU charter is invoked on March 29.

"It is a very complicated negotiating brief. I mean really complicated. It is going to be a mess and probably there will be no agreement," he says.

He believes there is little understanding among UK politicians and the British public as to the antipathy toward Brexit on the continent.

"They find it irritating, really irritating. It is important not to underestimate the ill will this has caused. From their point of view, keeping the European Union together is far more important than their relationship with Britain because it is a much bigger set of trading partners."

He believes the Conservative government led by Theresa May does not realize it is hopelessly out of its depth.

"I don't think they are up to it, but my God, I hope I am wrong. They don't understand the Europeans. They, in fact, despise the Europeans and they don't understand our interests. They are just not very bright."

Wolf, who is currently working on another book, The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, which is unlikely to be published before 2019, believes it is wrong to view the election of Donald Trump and the shift away from globalization as just aberrations.

"There is nothing more difficult than interpreting the longer term significance of contemporary events. I think we should all assume that it is not temporary, and that it may not necessarily go away."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn