China's Atlantis

Updated: 2012-05-09 08:01

By Eric Jou, Wang Zhenghua and Zhang Jianming (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Lion City is a bastion of a bygone era, hidden beneath about 30 meters of water. The pristine ruins of what was once home to about 5,400 people is receiving new attention, and some evacuated citizens have returned to recall the settlement's glory days. Eric Jou, Wang Zhenghua and Zhang Jianming travel to nearby Jiangjiazhen to rediscover the lost Lion City.

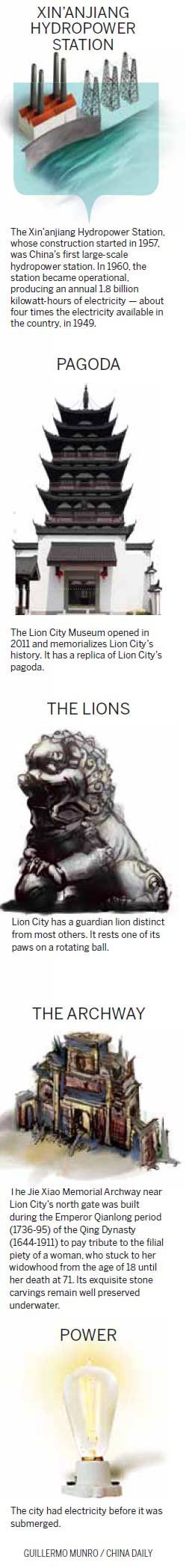

A treasure is hidden beneath the calm surface of Zhejiang province's Qiandaohu, or Thousand Island Lake, - an entire city. The ancient walled city in Sui'an county, called Lion City, because of the nearby Wushi (Five Lion) Mountains, has a history that spans 1,391 years.

The settlement, which is about half the size of the Forbidden City, was home to 5,371 residents. They were relocated when the government submerged the settlement to construct a national reservoir in 1959.

It remained out of sight and out of mind until now, as media are rediscovering the underwater ruins and residents are returning to remember the past and look to the future.

Reporters have been descending on the small town of Jiangjiazhen at the southern tip of Qiandaohu since the local government recently began efforts to bring the submerged city into the national consciousness.

The tiny town is one of the major relocation sites of Lion City's residents.

Just outside Jiangjiazhen is a museum dedicated to exhibiting the history of Lion City and its also-submerged neighbor, He Cheng.

Jiang Mingzhou, a 74-year-old resident of Zhejiang's provincial capital Hangzhou, searches for his childhood home in the museum's model of Lion City.

The schoolteacher was forced to leave in 1959 at age 21.

"I can see the street in the city's east where my house was," Jiang says.

"The city was really big. This model is really small. It's so incomplete. The school area was much larger, and the city wall had cannon turret platforms."

|

Jiang says he had no strong feelings about the move, aside from that he was doing his patriotic duty.

"We were told to move," he says.

"So, we did - no questions asked."

The government recently undertook the first underwater exploration of the ruins since 2002, with more than 200 journalists present, Lion City Museum board member Zhu Weizhou says.

"What's most important about Lion City is its 1,391 years of history," Zhu says.

"It represents one of China's greatest architectural feats. Many of the buildings are from the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties," he continues.

"It remains one of the country's best-preserved walled cities. It has survived the changes of the past 50 years, including such periods as the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76)."

Zhu says it's time for the ancient city to come to the forefront of modern minds.

The government is better able to protect such relics, because it has more resources, he says.

The best way to protect Lion City, Zhu says, is to leave it underwater.

And the thousands who moved out are preserving the chronicles of the settlement's last inhabited days by returning and reminiscing.

About 290,000 people from Sui'an county were moved in 1959, and the museum staff has spoken with many of them, Zhu says.

"They say the past was great, and the present is even better," Zhu says.

"We've learned from talking with them that they left out of a sense of duty but still feel a connection to Lion City. So, we built the museum to protect the city and give their memories new life."

Former resident and schoolteacher Yu Mingsheng agrees it was a higher calling that provided the motivation to move.

"I didn't want to leave," the 84-year-old says.

"But I was relocated to another school. I was originally a history teacher but became a librarian afterward."

Yu says he feels connected to Lion City, even though he was born elsewhere.

He has visited the site a few times to see what he can of his old home.

"I don't know much about the excavation process or current project," he says. "I just know there are a lot of artifacts underneath the lake. Many things were left during the move, and I'm sure some of it is of cultural importance."

Yu now lives in Qiandaohu city. While life at Lion City was good, he says his retirement in Qiandaohu is better.

China Central Television (CCTV) invited 75-year-old Tian Dongmen, who relocated to Fuzhou in Jiangxi province, to return for the exploration.

Tian says he was among the last to leave during the relocation in April 1959. He was part of a group responsible for ensuring others had left and heavy machinery had been shipped out.

He recalls moving to Jiangxi.

"Life was difficult," he recalls.

"We had received 264 yuan ($42) from the government but moved to the countryside. We suddenly went from living well to becoming farmers. Lion City had electricity, but we were moved to a place that only had oil lamps."

It was a drastic change in quality of life, Tian says.

In Lion City, he had time to sketch for fun. But he had to work hard to survive rural life. He also laments losing some of his personal possessions.

"There were some things we couldn't take with us," he says.

"We had a Qing Dynasty vase we had to destroy. It was huge, and people didn't have a sense of cultural artifact protection. Our thoughts were simpler back then. We thought about the greater good of the country, so we did things even when they were at our expense."

As CCTV's special guest, Tian took a boat on the lake and showed his sketches of, and poems about, Lion City. He swells with pride when he talks about his youth and sacrifice for his country.

"Some of the children scorned us adults because they were forced to move from their homes and the place they had known all their lives. But we didn't take it to heart. We were doing our duty for our country, and that was important to us."

Tian says he understands if future generations don't know Lion City's history and culture.

"There's nothing for them there," he says, smiling. "But it offers a chance to think of a simpler time."

He believes it's most important that people know there is a city under the lake.

"The money doesn't matter," he says. "You could give us all the money in the world, and we wouldn't know what to do with it. Future generations might not care, and we don't want to pass down stories of the hardships we faced. We just want the world to know we were there."

Contact the writers at ericjou@chinadaily.com.cn and wangzhenghua@chinadaily.com.cn.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|