Traditional ties that bind

Updated: 2012-06-23 02:56

By Pauline D. Loh (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

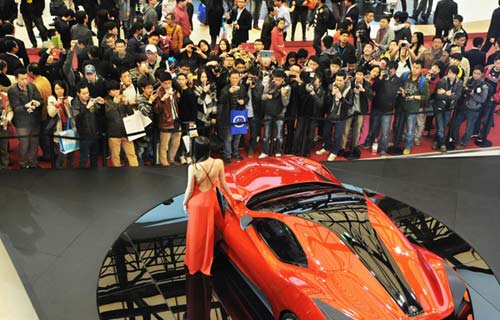

The centerpiece of Duanwu Festival — zongzi or rice dumplings — is always associated with family and culture. [Pauline D. Loh / China Daily] |

The Chinese celebrate Duanwu Festival by eating rice dumplings of all shapes and sizes. For some who live in other countries, it is a yearly tradition, just as their relatives at home guard the culinary heritage of both taste and culture. Pauline D. Loh explores the links between heart and home.

Traditions become precious when they become the only links to ancestral roots and historical heritage. This has always been the case, especially for people who wander, and no one has gone further afield than the Chinese. That is the reason why Duanwu is now a global festival, celebrated on all five continents. Studies have shown that the strongest guardians of traditional Chinese festivities are often overseas Chinese communities. In Chinatowns from the United Kingdom to the United States, lion and dragon dances are colorful components of Lunar New Year celebrations, just as the rice dumplings, or zongzi, are made and eaten at Duanwu in almost every major city in the world.

In countries nearer home where the Chinese Diaspora first landed, the humble rice dumpling has evolved and incorporated local tastes. Sometimes it is even borrowed for local festivals. In Vietnam, for example, dumplings are eaten most often for Tet, the Vietnamese New Year.

Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and the Philippines all have similar or evolved versions of the rice dumpling, while in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, they are so popular that zongzi are sold all year round, and prepared with local ingredients such as spices and chili.

Within China itself, regional varieties reflect local tastes and traditions, with savory dumplings popular south of the Yangtze River and predominantly sweet dumplings eaten in the north.

But one thread runs through it all — the eating of the rice dumplings commemorates a tradition that goes back thousands of years, associated with folklore and legends that include a colorful tale of poetry and patriotism, and a nationalistic pride that runs in the blood of the sons of the Yellow Emperor no matter how far they wander.

In the United States, second-generation ethnic Chinese are still familiar with the tastes of their ancestral home, even if they did lose some of the history in translation.

Donna Ma, 42, whose parents emigrated from Hong Kong, remembers growing up in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

"My mom would make zongzi, but my brothers and I just thought of them as another way to cook rice with meat. We knew there was some story about the parcels of rice and meat being thrown into the sea so that the body of some ‘good guy' would not be eaten by the fish.

"I do remember wondering how the fish were able to unwrap the parcels, as I had needed scissors to cut them open."

She was referring to the story of Qu Yuan (339-278 BC), the poet scholar from the Warring States Period who threw himself into the river in protest against rampant corruption in court. The people commemorated his convictions by making bundles of rice and sacrificing it to the river gods.

There is also a tradition of banging on drums and racing along the river in dragon boats to scare away fish and crustaceans that might otherwise have made a feast of the poet's body.

Ma's mother and grandmother kept the tradition alive each year by wrapping their own dumplings.

"Where we lived, we only had homemade zongzi. You couldn't buy them on the street like you could in China. If you didn't have a mom or grandmother making these for you, you missed out," Ma concludes.

Rebecca Lo, 43, a freelance writer in Hong Kong, grew up in Toronto, where her parents had settled.

"We don't have a holiday at Duanwu but I've always liked the fable associated with the festival in The Magic Pears, a children's book about ancient Chinese fables illustrated by my dad's artist friend," she says.

"My family is quite traditional and my parents have a lot of good friends who had also immigrated to Toronto. They would often give us handmade dumplings to thank my father for his kindness or for my mother — because she was always everyone's favorite. She was very beautiful when she was younger."

Lo's father is a Buddhist lecturer and an architectural and structural specialist.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|