Fairy-tale adventure

Updated: 2012-07-15 07:45

By Mike Peters (chinadaily.com.cn)

|

||||||||

His magical stamps of Hans Christian Andersen stories transported him to Denmark for the first-day-of-issue ceremonies, where he explored the 19th-century storyteller's birthplace. Mike Peters follows Shen Jiahong down the cobblestoned path.

Things are suddenly very cozy after a long and pleasant lunch. Artist Shen Jiahong and his colleagues from China Post are relaxing a bit after three hectic days in Denmark.

Table talk had broken down into small groups, drifting from tales of the workplace to stories from home. Shen reaches across the table's remnants of steak and salad with his iPhone, to show his Danish hosts the cherubic faces of two 3-year-old girls.

They are his daughters, Shen Xinran and Shen Weiran, a pair of twins we are invited to call "Cindy" and "Wendy". Shen, traveling outside China for the first time in his 41 years, clearly would like nothing more than to have those in his arms right now.

|

|

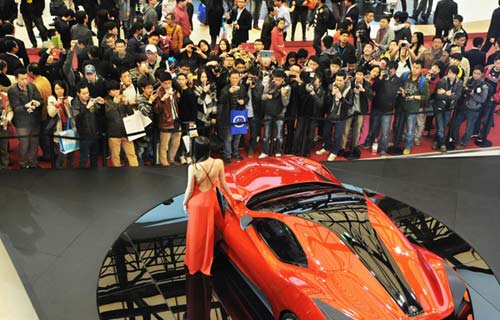

Shen Jiahong and a "swan" meet at the Danish embassy presentations of his designs, including The Wild Swan stamp (below). [Photo/ China Daily] |

He smiles as we lean in to ooh and ahh over his family pictures.

"I just like kids," he says.

Everyone around the table already knows that.

We have come with Shen to Odense, the birthplace of Hans Christian Andersen, because his colorful designs are appearing on four postage stamps that illustrate tales by the legendary storyteller.

It was no coincidence that Danmark Post had chosen International Children's Day to hold the event, and for the final photo opportunity, Shen was positioned in a sea of schoolchildren who had been invited to the museum for the day.

Suddenly the quiet designer - not his stamps - was the focus of the room. One girl reached up to hug him and, seeing cameras pivot in their direction, leaped into his arms for the Kodak moment.

Every youngster in the room suddenly swarmed to the delighted designer, and a few minutes later he had to back away from the crowd, laughing, before he was buried in a human avalanche. The kids begged on, wanting his autograph on their souvenirs and on their books. The luckiest got his neat signature on their arms.

For two hours earlier, Shen had sat at a side table with Swedish master engraver Martin Morck, who had etched the steel plates used to print Shen's images. The pair cheerfully autographed hundreds of envelopes known as "first-day covers", collectibles emblazoned with Andersen's top-hatted likeness.

On each envelope was at least one stamp bearing words that credit both men: "Shen Jiahong" and "Martin Morck". It's not the immortality of Hans Christian Andersen, but it's a brush with fame that swipes Shen with a wide stroke.

The Chinese artist enjoys the day and the task that brings him here, but he didn't get the fairy-tale stamp assignment because of any expertise on the subject.

The project, like every stamp set designed at China Post, was given to nine staff designers in an in-house competition.

Shen, the product of art school in his native Sichuan and the Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology in China's capital, has worked at the stamp agency for nine years. His brush strokes - camel-hair and computerized - have been behind six sets of stamps issued by his own country, including a pair celebrating the nursing profession issued in May this year.

China issues about 100 stamp designs each year, says Shi Yuan, the deputy director of the postal agency's editing and design department. He manages a staff that includes dozens of designers.

It's hard to stand out in a crowd like that, but the Danish judges of the storybook designs immediately gravitated to Shen's images. Each is a festival of secondary colors - orange, green, and purple - with outlines of white, not the usual black.

"The imagery was so immediate," says Morck, that not only were Shen's designs the clear winner, the judges didn't ask for any revisions.

"I think Shen has managed to bring both the elegant Chinese traditions of paper cutting and shadow play into a simple and in some way modern attitude," says Martin Pingel, design director of the Danish postal service. "There are not many extra elements, just the colors and the white lines. In northern Europe and in particular Denmark, we are very focused on the Mies van Der Rohe tradition of 'less is more'."

Pingel and his colleagues also liked the way Shen's designs reminded them of American record-album covers from the 1970s. "They have sort of a West Coast, Grateful Dead ambience that's really cool," says Pingel.

Shen is happy that his art resonates with the Danes. But the Grateful Dead? Record covers from the '70s? Born in 1971, he just shrugs, never having seen such things.

Pingel tells Danish television that although the designers who competed were deliberately all Chinese, "It was important that the design not be 'too Chinese'. We wanted a Chinese perspective on Andersen, but one that a Danish audience could still identify with. Striking that balance is what Shen's designs did very well."

Why was that hard?

For one thing, says Eric Messerschmidt, head of the Danish Cultural Institute in Beijing, Danes and Chinese look at the stories a little differently.

Danish literature has evolved a lot since the 19th century, he says, but Andersen's stories have only been part of the Chinese school curriculum since 1929. There have been a lot of ups and downs in Chinese intellectual society since.

"Andersen's stories seldom invoke happy endings," Messerschmidt says. "He presents life with real challenges, described in a hopeful, optimistic, beautiful way that Chinese can relate to."

In Denmark, he says, Andersen has become a literary figure with less importance for people's moral education, "whereas in China, he is still held up as an example."

Like Danish readers, however, Chinese fans do understand how profound the original stories can be - "breathtaking and tragic", Messerschmidt says, instead of the happy-ending formula of the Disney versions that have diluted Andersen's legacy in much of the West.

"If you ask Chinese, they will all have their favorite Andersen story and know the depths of it, even if they know the light version, too."

Shen agrees. "Most Chinese may like happy endings," the designer says, "but I think it doesn't matter if the ending is darker. I prefer a kind of open ending, giving more room to think about."

Shen tells a Danish TV interviewer - his first time on television - that his designs were inspired by Danish magazines, and he's "pleased to see the real Copenhagen and Odense".

He loves the pitched-roof houses, the cobblestone streets, and the carefully preserved churches and castles. But he was particularly thrilled to see the moon and stars aglow -impossible in a modern Beijing sky - an image at the heart of his favorite stamp design of the four, for What the Old Man Does Is Always Right - a story penned in 1861.

On his stamp, though, the sky is fantastically white - like the lines on all four stamps - which make the heavenly bodies stand out on the paper.

"White is the most important color in Chinese art," says Shen's boss, Shi Yuan, who accompanied the group to Denmark.

Using white ink for the engraved lines on the stamps was almost unique, says Pingel, who can recall only one other example, an Austrian stamp that showcased white lace on a blue background. White ink, which depends on a lot of mineral content to maintain its purity, can be a nightmare for printing-press operators, but the Danes admired the artistic vision behind Shen's choice and were pleased with the results.

The unusual coloration -plus the fact that the stamps are engraved from steel plates - makes them even more collectable, an important consideration for both the Danish and Chinese markets.

Both countries expect the fairy-tale stamps to be hot items in China. Danmark Post research has convinced that agency's officials that 20 million stamp collectors - about a third of the world's total - reside in China.

One of those is a Henan province native named Fan Bingchuan, who has collected stamps since he was in short pants.

Fan has turned up in Odense for the first-day-of-issue ceremonies because he's a fan of Shen's work. He's on vacation from his job as a driver, and he's catching the Danish event on his way back from an international stamp expo in Slovenia.

Fan has never met Shen before, but they've traded e-mails and phone calls, and Fan had told the artist that he'd be in Odense. Everyone else in the museum is shocked: the China Post artists work in relative obscurity, and for Shen to suddenly have a groupie turn up is almost surreal.

The TV reporters, who have been trolling the crowd for a new angle, pounce when they get wind of him. Suddenly Fan has his 15 minutes of fame, too.

The far-from-home philatelist - that's what stamp collectors are called - wishes aloud that Shen's fairy-tale stamps had been put out in China.

He needn't worry.

While the stamps can't be used on letters in Fan's home country - most letter writers in China don't actually lick and stick a stamp on mail anyway - Shen's colorful images are already easy to find from Harbin to Hong Kong.

Just before flying to Denmark, Shen and an entourage from China Post attended another "first day" ceremony, this one hosted by Danish Ambassador to China Friis Arne Petersen. Another International Children's Day celebration, this one had Beijing Radio host Xiaoyu Jiejie telling fairy tales to the children in the embassy garden.

Petersen, who also collected stamps as a boy, said he was first enchanted by China through Hans Christian Andersen story The Nightingale, which the great Dane wrote in 1844.

"And the great thing about stamps is the way they can reflect the beauty and refinement of an entire culture," he says. "When I see beautiful stamps, like these four, I want to own them."

That's precisely the hope of Danmark Post sales manager Bo Hoifelt, who has been working to make the stamps available in China.

"In the philately shops now there are close to 50,000 sets of the four stamps," he says.

"They were used in books in Chinese (only sold in China), a special children's product, a folder and sets of first-day covers." The Chinese products are unique, he adds, though there are similar books, folders and commemorative envelopes in English and Danish sold in Denmark.

How many will be snapped up by stamp collectors and how many by fairy-tale fans is anybody's guess.

"Andersen is so popular in China and his fairy tales have the largest group of readers in the world since they are in the curriculum," says Li Jinsheng, cultural counselor at the Chinese embassy in Denmark. "Many Chinese got to know Denmark through H.C. Andersen and his fairy tales - and get to know today that Denmark is also a country famous for its innovation, green energy, high technology, social management and so on."

Shen Jiahong returns home with two tiny Georg Jensen silver angels - souvenirs for his daughters - and a simpler take on the Andersen legacy.

"Those Danish kids, they were so lovely," the designer says. "I felt as if I went back to that age. Children listen to fairy tales, while they also have the main roles in fairy tales. The whole thing should belong to them."

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|