Rural doctors bring hope

Updated: 2013-01-09 07:32

By Yang Wanli and Tang Yue (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Low incomes

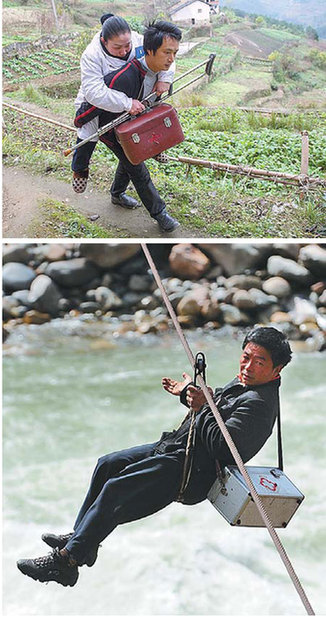

Zhou Yuehua, a 43-year-old village doctor from Chongqing in Southwest China, has difficulty walking. However, despite suffering from poliomyelitis, an acute infectious disease that causes flaccid paralysis of the muscles, Zhou continues to visit her patients every day with the help of her husband, Ai Qi, who sometimes carries his wife on his back as she makes her rounds. According to Zhou, low pay is a common problem among village doctors.

|

|

Top: Zhou Yuehua, 43, from Chongqing, who has difficulty walking, visits her patients every day with the help of her husband Ai Qi. Chen Cheng / Xinhua Above: Deng Qiandui, a village doctor in Nujiang prefecture, Yunnan province has spent 28 years accessing his patients by sliding across the Nujiang river. Pan Wenhai / Xinhua |

In the coastal province of Jiangsu, a county-level village doctor earns around $2,407 annually. They were once allowed to set their own prices for medicine, but the practice was regulated when China's National Basic Medicine System was introduced two years ago.

"I earn just enough for the basic living requirements of two people, my husband and me. Sometimes, we don't charge senior patients with no wages. Our income would make raising a child almost impossible," said Zhou.

In some rural areas, a village doctor can have more than 1,000 patients, most of whom have difficulty accessing pensions or social insurance systems.

Free treatment

The doctors don't just save the lives of the villagers, sometimes they are also saved by their patients.

In 1998, after three years at a technical school, Li Qianfeng opened a clinic in his hometown of Liuhe in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. He earned about 3,000 yuan ($481) a month and life was comfortable. However, his life changed when he heard about patients from Dalang village, who had to travel for hours to reach Liuhe.

"People told me that some patients weren't well enough to travel that far to see the doctor. Patients who were too fragile to walk were transported to the township on litters dragged by fellow villagers. Some just died halfway through the journey," said Li.

In 2003, he closed his clinic and moved to Dalang village, which consists of eight hamlets. The hamlet furthest from Li's base is 15 km away, but he walks there at least twice a week.

While the workload became heavier, Li's salary shrank. Without a hospital post, he was unable to draw a government salary. At first, he made just 30 yuan a month, although that rose to 300 yuan in 2009, and his profit from the sale of medicines brings in a further 1,000 yuan.

Village doctors are allowed to sell medicine at a profit of up to 15 percent. But Li just charges poor villagers cost price and sometimes provides free medicine for destitute patients.

"It's not just me. A lot of village doctors don't charge for treatment and also provide free medicine to patients unable to pay," said Li, 33. "It may be as little as five yuan. It's nothing to wealthier people, but that sum could provide cooking salt for families for many months," he said.

In May 2008, Li saw things from the patients' point of view when he was diagnosed with uremia, a potentially fatal condition that can cause a kidney failure. Without medical insurance, he had to pay the bill for treatment himself. His family spent all their savings, but was unable to provide the 200,000 yuan needed to pay for a kidney transplant.

When they heard the news, many of the villagers were distraught and brought Li rice, vegetables and fish. They also bombarded the media with letters telling of their village doctor's plight. The letter campaign resulted in donations from the public and HK$930,000 ($120,000) from a charity in Hong Kong. Li underwent a kidney transplant in December 2008.

Although the doctors advised him to give up his work in the villages, he returned two months later. "I felt I owed my life to the villagers, so I couldn't leave," said Li.

Li said he hopes his 7-year-old daughter will also become a village doctor and urged more young people to serve patients in rural areas.

"It's not their fault. The younger generation is reluctant to work in the rural areas because of the poor conditions and pitiful salary. There is no insurance and they won't receive a pension," he said.

"I hope the problem will be solved as soon as possible so more doctors will be based in these areas and patients won't have to walk for hours to get treatment."

He Na contributed to this story.

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Venezuelan court rules out manual votes counting

Venezuelan court rules out manual votes counting

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Boston bombing suspect reported cornered on boat

7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|