Life and death in the house of hope

Updated: 2016-05-17 08:04

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Sometimes, infection occurs in the middle of a course of chemotherapy, so the treatment has to be suspended and cannot be resumed until the patient has recovered completely.

However, under the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, the 30,000 yuan upper limit for chemotherapy is only applicable for the child's first uninterrupted treatment, so resumption of treatment is not covered.

The picture for children undergoing stem cell transplants is not necessarily better.

"Among all the leukemia children in Wujianong, Li Ao's treatment has cost the most," Li Guoping said.

The boy stayed in the transplant ward for 90 days between June and September.

"It normally takes about a month for the transplanted cells to engraft, or take, after which they begin to multiply and make new blood cells," he said. "But my boy rejected very violently. He also suffered serious gastrointestinal problems that caused him to defecate a couple of dozen times a day and there was blood in his feces."

The 54-year-old remembers the boy's strange smell the day he left the "cabin", as the transplant ward is known.

Seeing Wu Qiaoqiao, a 9-year-old patient who lives with her mother in Wujianong, evoked many memories for Li Guoping. Having had a stem cell transplant barely four months ago, the once sprightly girl has been plagued by relentless mouth sores and acute pancreatitis - both common side effects - and now weighs just 12 kilograms. Her skeletal limbs are covered by blackened skin that is expected to slough off in the next few months.

"They call it a rebirth - you shed your old self for a new one," Yu Wenhuan, Wu's mother, said. "But it's a rebirth only for those who can make the passage. We are already up to our necks in debt."

Yu, who was three months pregnant, said she was made to feel guilty by her daughter's reaction.

"A few days ago, I was lying on the bed feeling totally spent, when she walked slowly toward me and handed me her own bottle of milk, the only thing she can eat because of her illness," she said.

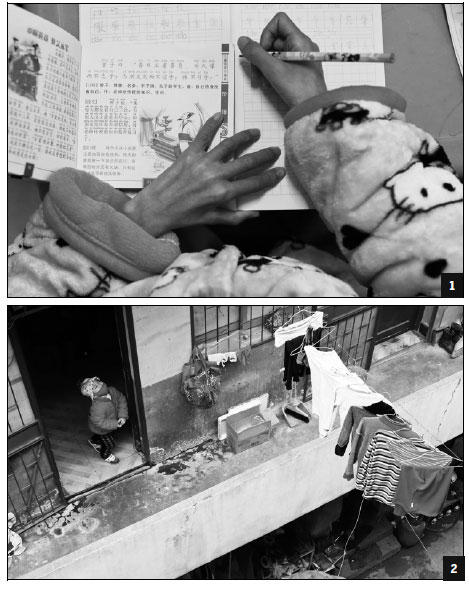

Wang Yupei, who works for a local NGO called The Happy Childhood Charity, believes that life and disease are inseparable for Wujianong's leukemia children. "An often-played game here is doctor-and-patient, with them acting as the doctors and us, the patient. They never forget to 'sterilize' before an injection," the 23-year-old said.

The NGO, founded in 2011 by former solider Wang Dacheng, aims to provide an environment for the sick children to mingle and have fun. Located at the entrance of the lane, the 7-square-meter room is the only place where the children appear as normal as others of the same age, except for the vividly-colored masks that hide their faces.

"Money is probably what they need the most, but trying to help in that respect is very likely to put us in an awkward situation with the families," Wang Yupei said. "Desperation has driven them to compete among themselves for benefits real or imagined. Sometimes, all it takes to create a palpable sense of tension is a good-willed outsider who has come to help."

Wang Fei, a doctor at the Hospital of the Capital Institute of Pediatrics in Beijing, believes the central government and the health ministry should be more aggressive and allow more latitude in the provision of financial help for children in need.

"Many hospitals in the West are allowed to collect donations for their patients. I know there are a lot of people out there who want to donate, and ours is a channel they can trust," she said. "But sadly, as a hospital we are not legally entitled to receive the money.

"Given proper treatment, the five-year survival rate for children with leukemia, especially acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common type among children, could reach 70 percent," the 44-year-old continued.

"The government needs to greatly raise the level of medical insurance if the flame of hope is to burn continually for these families."

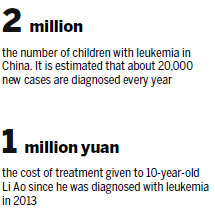

Every morning, Li Defang wakes at about 4 am and immediately goes out, leaving Zhao Jing, her granddaughter, sleeping in bed. "I collect a few plastic bottles, some newspapers and old cardboard - stuff that I can sell for a few yuan, if I'm lucky," the 54-year-old said.

"My only worry is that she might kick away the quilt when she's sleeping and I'm away. She can't afford another infection."

While her grandmother was talking, Zhao Jing was fumbling with the old tricycle. "Do you want a new one?" a neighbor asked her.

The little girl's voice was muffled by her face mask, but her eyes were big and clear. She looked intently at the man for a moment. "No, no, no new bike," she replied. "I want money. I want medicine." Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

- Canadian PM to introduce transgender rights bill

- Hillary Clinton says her husband not to serve in her cabinet

- New York cake show designs fool your eyes

- ROK prosecutors seek 17-year prison term for attacker of US envoy

- World's biggest plane leaves Australia

- Conference calls for females to be put at forefront of development

Apple's CEO Tim Cook's eight visits to China in four years

Apple's CEO Tim Cook's eight visits to China in four years

Annual New York cake show designs fool your eyes

Annual New York cake show designs fool your eyes

Divers find ancient Roman cargo from shipwreck in Israel

Divers find ancient Roman cargo from shipwreck in Israel

Taoist priests worship their ancestors in Central China

Taoist priests worship their ancestors in Central China

The world in photos: May 9-May 15

The world in photos: May 9-May 15

Top 10 most generous companies in China

Top 10 most generous companies in China

Wine market shrugs off slump

Wine market shrugs off slump

Terracotta teddy bears debut in Wuxi

Terracotta teddy bears debut in Wuxi

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Liang avoids jail in shooting death

China's finance minister addresses ratings downgrade

Duke alumni visit Chinese Embassy

Marriott unlikely to top Anbang offer for Starwood: Observers

Chinese biopharma debuts on Nasdaq

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

US Weekly

|

|