Genetic tests - turning curiosity into surety

|

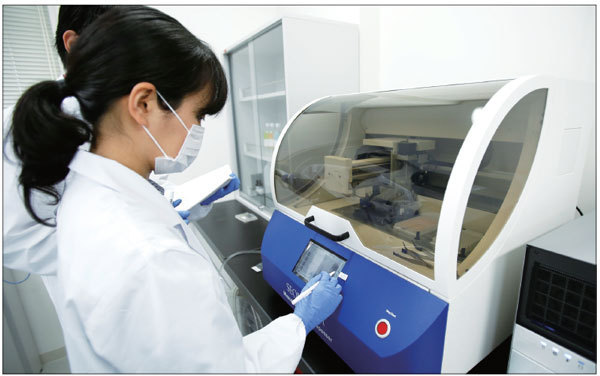

Laboratory technicians at work on a direct-to-consumer genetic testing service “Mycode” at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Medical Science in Japan. Biotech companies have also fl ourished on the Chinese mainland to promote public awareness of genetic technology. Kiyoshi Ota / Bloomberg |

Nascent market tipped to 'explode' in 2019 despite doubts about accuracy

Yuan Kaijie recently received a special gift - a genetic test to tell if he's a good drinker.

It was a "tipsy" test with a little container inside a box, and he was curious to find out how he would be ranked among the boozing crowd.

"The test is very simple," said Yuan. All he had to do was to spit saliva into the container and had it sent to a genetic testing company pre-paid. About four working days later, the results came through WeChat, saying he's actually capable of drinking more alcohol than 70 percent of people.

According to the report, Yuan has a strong ability to metabolize alcohol and aldehyde, which indicate the level of alcoholic drinks' influence on humans, but it warns that the possibility of him being addicted to alcohol is also high.

Genetic tests used to be a medical method of identifying an individual's genetic condition in order to help determine his or her chance of developing or passing on certain diseases. Traditionally, such tests are available only through hospitals and applied for diagnosing and treating rare diseases. But, many direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic tests have appeared and are growing quickly, promoting public awareness of genetic technology. Though their usefulness and accuracy remain doubtful, curiosity is driving some people to try them out.

A DTC genetic test provides access to a person's genetic information without relying on medical facilities or leaving the home. A user just needs to collect his or her DNA sample by swabbing the inside of the check, or spit saliva, and mail it back to a lab for a test. The digital results will be sent online.

Instead of identifying certain diseases, the test focuses on interesting characteristics close to people's everyday lives, such as ancestral origins, inborn skin quality, athletic talent, and demand for vitamins or metabolic capacity - even to tell a dog's ancestral origins.

There are also products to determine the chance of having certain inherited diseases and traits, and are available through internet platforms.

The "tipsy" test that Yuan took is developed by Genebook - an e-commerce platform for gene-related products established by China's genomics giant BGI.

The Shenzhen-based company was set up in 1999 and has become the world's largest genomic organization, focusing on research and applications in the healthcare, agriculture, conservation and environmental fields, according to its website.

Guan Xin, vice-president of the internet products center at BGI, said "tipsy" is one of the company's most popular products with a sales volume of tens of thousands of kits in the first year despite low-keyed promotion. "Many people may think that genetic testing could be expensive, costing hundreds of thousands of yuan and is only used for rare illnesses. But, our internet-based production tells them that such technology could be very close to us," he said.

Apart from the simple and painless process, the low price is also another appeal for those who are curious to have a try. For example, the price of taking a "tipsy" test is just 99 yuan.

Somur - a Beijing-based biotechnology company - has launched more than 200 internet-based genetic testing products, all priced at below 100 yuan, and some cost just one yuan for early-stage promotion.

The cost of such technology has dropped sharply in recent years as it advanced. The cost of sequencing a genome - the total genetic composition of an individual - was reduced from $100 million in 2001 to about $1,000 in 2015 - and is still going down, while DTC genetic tests only look at one or a few variations.

However, Cheung Ching-lung, assistant professor of the Centre for Genomic Sciences at the Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy at the University of Hong Kong, said: "Genetic markers may be able to predict drinking behavior or ability, but people don't really need to do the genetic test to tell whether they can drink or are allergic to alcohol." He said more than 90 percent of these tests are not useful, especially those involving facial products. "There are only a handful of genetic tests proven to be clinically useful, like severe adverse drug reaction (potentially fatal ones), disease complications and prenatal diagnosis."

Cheung also doubted its accuracy and does not recommend a genetic test without recommendation from doctors or healthcare professionals, otherwise it may lead to further unnecessary problems. But he believes that, in 10 years' time, genetic variation, together with other lifestyle factors, will be useful in predicting diseases and treatments.

Guan said BGI can guarantee the accuracy of its genetic tests, but some diseases and other health issues are also under the influence of postnatal environment and its certainty needs further scientific breakthrough. In his opinion, DTC genetic tests are to increase people's awareness of gene technology and change the process of taking a genetic test.

More importantly, he believes that gene production helps people establish the concept of preventive medicine and make them aware of their health and act before a disease sets in.

As to the security of users' gene data, Guan said samples of DTC production buyers will be sent to China National Genebank for storage after testing, and users also can ask for them to be disposed of any time.

As a user, Yuan, who works for a technology company in Shenzhen, found the result of his test was mostly in line with the fact. "But, compared to its accuracy, I'm more interested in the fun product itself," he said.

According to the database of technology information provider TMTpost, more than 100 startups have joined the industry despite doubts about the accuracy of genetic tests.

Zhou Kun, who founded "23mofang" in 2015 in Sichuan province, said he expects the nascent market to "explode" in 2019 with 1 million users, according to news portal sohu.com. The startup recently announced a B-round financing of 40 million yuan, and conducted 27,000 tests last year, raking in tens of millions of yuan in revenue.

Mo Renying, an analyst at VCBeat Research, an industry research organization, said in a report that the overall market of gene sequencing and related sectors may reach 100 billion yuan, while DTC tests would account for 10 percent.

"Most of them are now targeting non-rigid demand and their technology is similar," she said, but still believes that its proportion will further expand as costs continue to fall in future.

Fitness, beauty and insurance companies have also joined the sector, utilizing genetic testing as a supplementary method to examine a client's body and skin quality. A weight-losing camp organizer named Jianfeidaren in Shenzhen - one of the biggest in China - teamed up with BGI recently, embedding the latter's technology into clients' physical quality check.

Chen Huayi, the camp's vice-general manager, said their clients are "very excited" to see such new service, but it's still in the pilot stage and has yet to begin full production.

But the prospects for DTC generic testing remain uncertain. When people's curiosity runs out, it may face with serious trouble unless it can prove itself as a useful and reliable product.

grace@chinadailyhk.com