'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

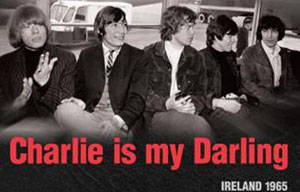

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Building new lives

Updated: 2012-03-29 09:38

By Cheng Anqi, Zhang Zixuan and Han Bingbin (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

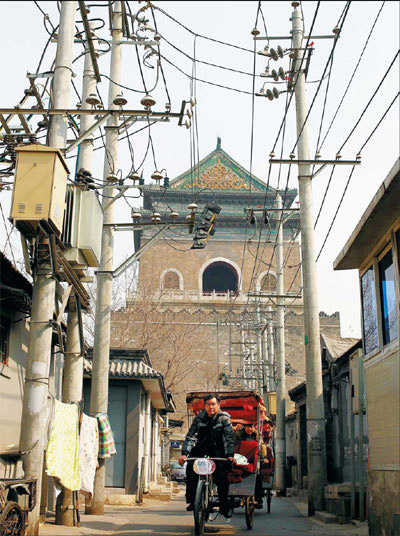

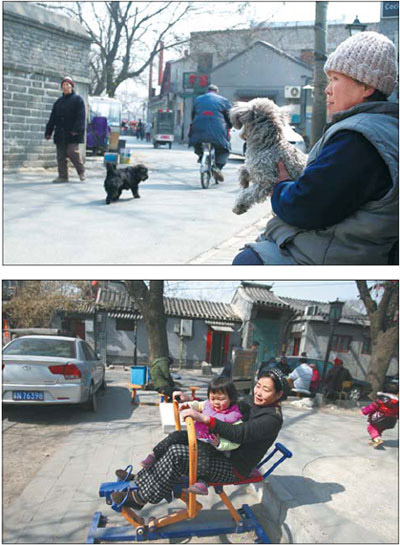

Editor's note: Fierce controversy has built up around the planned demolition and renovation of the area surrounding Beijing's Drum and Bell towers. Some residents, especially those living in poor conditions, can't wait to be relocated. Others say they will resist. The complexities surround concerns about the remoteness of resettlement locations, compensation and the disintegration of longstanding communities. This special report examines the various dimensions of the demolition and renovation.

Or demolishing old bonds? These are the questions facing planners and residents who live near Beijing's Drum and Bell towers. Cheng Anqi, Zhang Zixuan and Han Bingbin report in Beijing.

The Geng family can't wait to move out of their miserable living conditions. Li Lihong's folks do not plan on going anywhere if they can help it. These households represent, perhaps, the spectrum of sentiment among residents to be relocated from the area surrounding Beijing's Drum and Bell towers. Residents will be moved to the city's fringes by government order to clear the way for redevelopment by a private company that intends to transform the residential area into a cultural industry and tourism zone. The first phase will relocate 146 households. The 66-year-old matriarch of the Geng household, who refuses to give her surname, says she has been waiting for the renovation since plans were announced in the 1950s.

Her seven-member family, which spans three generations, crams into a 12-sq-m space with a 2-sq-m separate space that serves as a kitchen.

Geng is tired of being rained on while transporting food from the kitchen to the living area.

"I use three rooms to prepare lunch," she says.

Because there is no gas line, she operates a homemade rig to cook. The family placed buckets of water on the roof to heat them for summertime showers until an electric water heater made showers in their house possible in the warmer months. The family then hikes the chilly distance to the public shower, which is difficult for Geng's son, who has a leg disability, and has often made her granddaughter sick.

Her 45-year-old son, who refused to be named, strongly opposes many experts' views that the government should keep the hutong as they are.

"These experts probably have several houses, so they don't really get to understand our pain," he says.

But money is his first question about the relocation.

"It all depends on how much compensation we get. If the government gives us 20 million yuan ($3.17 million), I would be happy even if they relocate me to Hebei province."

But aside from price, he says the family needs at least three 20-sq-m apartments.

If the relocation is aborted again, he suggests the government convert homes into courtyards. He would be happy with a 70-sq-m courtyard, he says.

Li's public rental home, which costs the family slightly more than 100 yuan a month, is 20 sq m, plus a 10-sq-m room built for her son and his wife.

"The relocation team asked how much we would accept in compensation the day they came to measure our houses," Li says.

"I won't even think about it. We're not leaving. Those who want to leave have bad living conditions or want big compensation."

The 58-year-old says she has heard the neighborhood will be renovated into luxury courtyards for foreigners. She says this angers and confuses her.

"I don't understand why people who have long lived in the city's heart should be pushed to the outskirts," she says.

There are practical reasons for wanting to retain their current hukou (residency permit).

"My son doesn't have a job now, but there are even fewer opportunities in the suburbs. What about my grandchildren's lives? If they're born in the suburbs, they'll miss out on better education and healthcare options available in the city."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

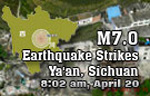

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|