'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

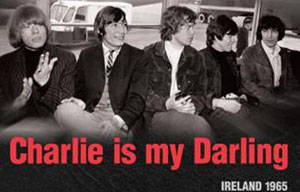

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Between the lines

Updated: 2012-09-03 09:01

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Characters from A Dream of Red Mansions such as Lin Daiyu (left) and Jia Baoyu are well known to most Chinese through the book itself and its many adaptations. Photos Provided to China Daily |

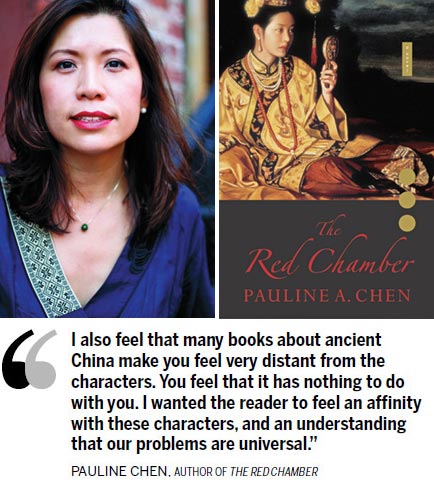

Literature teacher Pauline Chen has revised the classic tale A Dream of Red Mansions to make it more accessible to a new generation of Americans. Kelly Chung Dawson reports in New York.

In Cao Xueqin's 18th century novel A Dream of Red Mansions (also known as Dream of Red Chamber) a love triangle between a young man and his female cousins became China's own Romeo and Juliet - and today forms the basis of Pauline Chen's streamlined update of the classic story, which originally featured 400 characters over 2,500 pages.

Chen's The Red Chamber focuses on the passionate, free-spirited Lin Daiyu, who lives with her extended family at Rongguo Mansion after the death of her parents; and Xue Baochai, her well-behaved, intelligent cousin. Both vie for the hand of Jia Baoyu, the heir to the Jia family fortune.

"These two women represent the two ways that a Chinese woman can be," Chen says. "They are important archetypes. To me, this love triangle is very powerful, because in a way, these women represent a struggle for individualism in China.

"There aren't many love stories in Chinese literature, because at the time nearly all marriages were arranged. Even today, China is still a culture where filial obligations are emphasized, so this idea of wild, romantic love really appeals to people."

Chen, who grew up in the United States and has Taiwan-born parents, has a PhD in East Asian studies from Princeton. As a literature teacher, she became frustrated by the difficulty with which her American students approached A Dream of Red Mansions.

The book was too long, the cast of characters overwhelming. Additionally, the structure of the original does not follow Western conventions, she says. There is no central conflict and the plot meanders in episodic turns. She decided to rewrite the book, in the hope of introducing the story to a wider audience.

"My feeling was that most Americans think of pre-modern China as being barbaric and that always bothered me," she says.

"It's not that simple. Yes, Chinese society was oppressive for women, but it was also a sophisticated and rich society, and a complicated one.

"I wanted to communicate those complexities. I also feel that many books about ancient China make you feel very distant from the characters. You feel that it has nothing to do with you. I wanted the reader to feel an affinity with these characters, and an understanding that our problems are universal."

Emily Wilson, a former student who took Chen's course on classic Chinese literature at Oberlin in 2010, says that she found the original book overwhelming.

"Contemporary American literature, especially commercial literature, often does not attempt to encompass the complexities found in the original A Dream of Red Mansions," she says.

"But Professor Chen's incredible understanding of the original text allowed her to highlight more abstract thematic patterns. She also had a very nuanced understanding of the emotional motives of the various female protagonists."

The task of adapting this book in particular is a difficult one, says Daniel Youd, associate professor of Chinese language and literature at Beloit College in Wisconsin. Previous adaptations have faced high expectations, and have often fallen short.

"Ever since the original novel was written, people have not stopped reading and adapting it," he says. "Anyone who tries to remake the story is in good company, but is also running a very high risk because people are so attached to the story. It's very brave to attempt to retell this story."

American audiences will likely have fewer expectations though, he says.

"In adapting the story for Chinese readers, one has to take into account deep levels of cultural expectation, because the characters are already so vividly ingrained in the Chinese imagination. But the objective with the American audience will be to introduce the characters, and I think Pauline does a great job of bridging the gap."

For Chen, the women are the backbone of the book, she says. In addition to Lin Daiyu and Xue Baochai, the powerful Wang Xifeng plays a central part in the story. Wang manages the finances of the house, lends money at interest and manipulates the people around her for personal gain.

"She was the prototype of a modern businesswoman," Chen says. "Before reading the original book, I had this idea that women in ancient China were powerless, but this character was extremely bold. All the female characters were so complex, and richly drawn. They were living in this complicated hierarchy with so many bonds and obligations.

"In some ways, for me, it really mirrored how a modern woman feels, dealing with children, a career, aging parents and in-laws. I thought it was relevant to our lives today, and I loved the female characters."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|