'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Mo pens Nobel success story

Updated: 2012-10-12 09:55

By Liu Wei (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

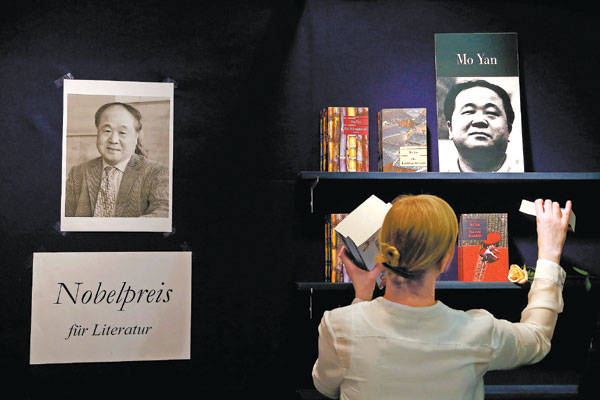

Books by Mo Yan are put on prominent display at the Frankfurt book fair on Thursday. Mo is the first Chinese national to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Ralph Orlowski / Reuters |

|

|

Mo Yan meets the press at his hometown in Gaomi county, Shandong province, after the announcement of his winning this year's Nobel prize in literature. Provided to China Daily |

Writer praised for 'hallucinatory realism' wins recognition from the Swedish Academy, Liu Wei reports.

Writer Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature on Thursday. The Swedish Academy, which gives out the annual prizes, described Mo's works as "hallucinatory realism" merging "folk tales, history and the contemporary".

"Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives, Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent in its complexity of those in the writings of William Faulkner and Gabriel Garca Mrquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition," according to the citation for the award.

Mo, 57, whose real name is Guan Moye, is the first Chinese writer to win the honor, which also comes with a financial award of 8 million Swedish krona, or $1.2 million.

"I grew up in an environment immersed with (Chinese) folk culture, which inevitably come into my novels when I pick up a pen to write. This has definitely affected - even decided - my works' artistic style," Mo told a group of reporters at a hotel in his hometown of Gaomi, in Shandong province, shortly after he won the award.

"Mo Yan deserves the prize simply for being a great writer," said Eric Abrahamsen, a seasoned critic and founder of Paper Republic, an English-language website on Chinese literature.

"Throughout his career he has done much to develop the language and style of contemporary Chinese literature, and he has also tackled many of the 'big' historical and social themes of contemporary China."

The buzz on Chinese media about Mo possibly winning the prize started about a month ago, when some betting agencies started placing Mo as a contender.

In early October, British bookmakers Ladbrokes put Mo next to Japanese writer Haruki Murakami as the leading bets but Murakami had odds of 3 to 1, while Mo lagged behind at 8 to 1.

Although China boasts a tradition of literature and scholarship, few writers have won international acclaim and recognition. And for that reason, the Nobel Prize for Literature has always been an aspiration for Chinese writers. Mo's win will shift the focus to more previously unknown Chinese works.

Although he has allowed few media interviews, Mo is well known.

In contrast with his appearance, his works are anything but down home and country. They are dramatic, with "a unique style, sharp language, wild imagination and magnificent narration," according to Ye Kai, a senior editor who has edited Mo's works.

Mo created a cast of colorful characters, and once said that if there was a prototype, it would be the abandoned and ignored "black boy" who first appeared in the 1985 novella Red Transparent Radish, which may bear imprints of the author's childhood.

Mo's family was categorized as rich middle-class peasants, which meant he was close to being labeled "class enemy". He dropped out of school and became a cowherd. At 20, he left his hometown and joined the army.

In another 1985 novella White Dong Swing, Mo first wrote about Gaomi Northeast Township, generally believed to be based on his hometown in East China's Shandong province. In a short story published the same year, Autumn Water, he mentioned the landscape again.

Gaomi county is to Mo what Yoknapatawpha county was to William Faulkner. It is where most of his stories happen, and a land which inspired him throughout his 31-year writing career.

Many got to know of Mo when director Zhang Yimou adapted the film Red Sorghum from his 1986 novella of the same name, bringing to life a visual landscape characterized by red sorghum fields and a fiery setting sun.

Set in Gaomi, the story is the tale of a sedan carrier who saves the bride he is carrying from bandits, and later marries her. The wild, audacious man urinates in the local winery's precious barrels, but also later dies fighting against Japanese troops during World War II.

Editor Ye Kai has high praises for this work, calling it an ode to the power of life.

Mo left the army in 1997 and gradually developed a writing style all his own. History, family sagas, blood and violence are frequent elements in his most famous works, such as Big Breasts and Wide Hips and Sandalwood Penalty.

Howard Goldblatt, who translated many of his works and is an acclaimed scholar of modern and contemporary Chinese literature, finds Mo's novels reminiscent of Charles Dickens' writings - big, bold works with florid, imagistic, powerful writing and a strong moral core.

He also sees parallels with works like William Vollmann's Europe Central such as Red Sorghum, with its historical sweep, and The Garlic Ballads, with the trenchant criticism of monstrous behavior by those in power.

In Mo's works Goldblatt see influences of the modernist Faulkner, the magic-realist Garcia Marquez, Oe Kenzaburo, and last but not the least, Francois Rabelais, with his "bawdy humor and scatological exuberances".

Not all were convinced that Mo deserved to win. Some writers and critics attacked Mo on his perspectives rather than talent, and cast doubts that he could be objective and independent enough when discussing serious social issues in his works. They believed his winning of the Nobel Prize was in direct conflict with his position as the vice-chairman of the official Chinese Writers' Association.

But Ye Kai disagrees and quotes Mo's 2010 novel Frog as an example. He argues that the plot tackles a sensitive issue, China's family planning policy. Mo's protagonist, the Aunt, helped deliver thousands of babies in Gaomi Northeast Township shortly after 1949, but in the 1970s and 80s', she became an abortionist as she imposed the family planning policy. In her later years, the midwife atones with the making of thousands of clay babies and reads Buddhist sutras to them.

"Some people think the book is an ode to the family planning policy, I don't think they really understand it," Ye writes in his blog.

In an earlier interview with China Daily, Mo said the conscience of a writer does not allow him to avoid the issue, and he hopes people will finally see that "of all things in the world, life is the most valuable".

Goldblatt says another important work, The Republic of Wine, is the most technically innovative and sophisticated novel from China that he has read. In a work full of his signature surrealism and rich metaphors, Mo traces an official who went to the fictional Republic of Wine to investigate whether the rumor that people are eating babies was true. Before he could start, local officials talked him into getting drunk and he drowns in a pit of excrement before he could do any investigation.

The novel is widely considered a satire against both the corruption of officials and the pedantic part of Chinese drinking habits.

Paper Republic's Abrahamsen appreciates Mo's poise between literary and analytic aspirations best.

"Chinese literature can often go to one extreme or the other," he says. "Either it's an exposition of a writer's opinions about a social issue, sacrificing literary value, or else it's a work that retreats from reality and plays games with imagination. I think Mo Yan has kept the balance."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|