Money talks and Wang Feng sings

Updated: 2012-03-16 10:14

By Mu Qian (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

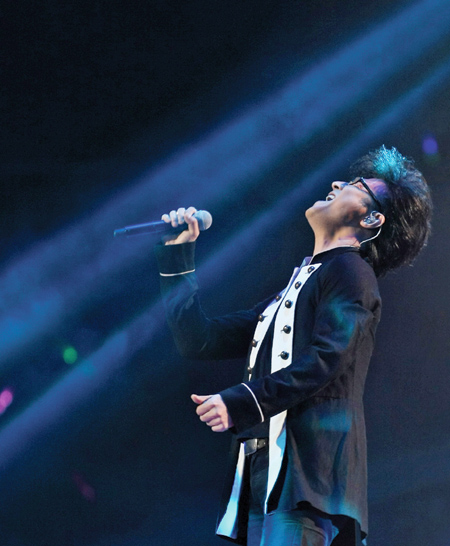

Wang Feng, one of China's most famous pop rock musicians. Xu Peiqin / For China Daily |

Global Business magazine doesn't often deal with music, but a recent article about pop rock musician Wang Feng has captivated public attention.

It's unsurprising many insights about Chinese culture and art come from financial media. An economic lens is often the best viewfinder for interpreting cultural phenomena in a country where everyone talks about development all the time.

The article, entitled Deliberate Blooming - a wordplay on Wang's hit song, Blooming Life - compares Wang's resilience in China's barren music market to other rockers' inability to adapt.

Wang, who trained as a viola player at the prestigious Central Conservatory of Music, forsook his classical music career to form a rock band called No 43 Baojia Street in the 1990s. But stardom found him only after he disbanded the group and became a solo artist.

Virtually every Chinese has heard of Wang's Flying Higher, which aired on China Central Television on such important occasions as the launch of the Shenzhou VI manned spacecraft and the Beijing Olympic Games. The song was also used in a China Mobile TV commercial.

"When Wang found he was invited by many enterprises, banks and even large-scale international event organizers because of a certain encouraging and uplifting quality, he and his manager began to 'go around singing karaoke' with a CD of accompaniment music," the article's author, Ji Yi, writes.

Wang's former manager, Jiang Nanyang, was quoted as saying that 90 percent of Wang's income came from "singing karaoke".

Wang's success discloses the embarrassing truth that even one of China's most popular singers has to rely on the patronage of governmental organizations and big companies, who support certain music not because of the music itself but because of its practical function.

Born in 1971, Wang is 10 years younger than China's "godfather of rock music" Cui Jian.

And he faces an environment different from his forerunners.

While the first Chinese rockers awakened large crowds with their revolutionary power and sold millions of cassette tapes, Wang finds himself in an age when idealism has been smothered by reality.

After releasing two albums with No 43 Baojia Street, Wang disbanded the group and signed with Warner Music, because the company wouldn't sign the whole band but found commercial potential in Wang.

With songs like Flying Higher, Brave Heart and Blooming Life, Wang became "entrepreneurs' favorite rock singer". That's because the uplifting spirit of those songs is what Chinese entrepreneurs share and want to use to bring cheer to their employees.

So Wang is flooded with invitations to corporate events at the end of every year.

It was this adoration of optimism that led General Motors to select Wang to promote the Chevrolet Captiva. It was the first time a Chinese rocker signed an advertising contract with a multinational corporation.

Wang took to his micro blog to deny his success comes from catering to the market, after the article was published.

He writes: "Any effort to fuse rock music with commercial considerations is stupid. Only probing humanity and the soul is beneficial!"

I saw No 43 Baojia Street live in the late '90s and bought their first album.

They were not really a mature band, and influences from the Beatles and Cui were conspicuous.

But there was a rawness and critical attitude in their songs that was worthwhile but, unfortunately, lost in Wang's solo works.

Global Business reports Blooming Life was originally entitled Machine - an accusation that society renders "blooming life as a discarded machine".

The record company originally canceled the song, because they believed it was too negative. But, at his manager's suggestion, Wang changed the lyrics to: "I want a blooming life, just like flying in the boundless sky."

Everyone has his or her own choice of career. There's nothing about Wang we can rebuke.

But the question is: Why do Chinese officials and entrepreneurs prefer Wang's songs over other artists'?

TV and the news media continue lauding the achievements of China, now the world's second largest economy.

Go to the airport, and you can't avoid videos of people preaching their formulas for success.

Walk down the street, and you are handed one leaflet after another about English-language courses that promise to change your destiny.

This is an era of dreams and legends.

And Wang, deliberately or not, conspires to paint a picture of a blooming age.

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

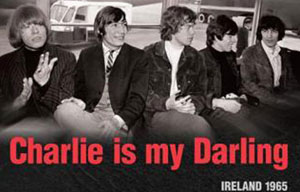

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|