Life

The first Chinese to gamble on Wild West

Updated: 2011-04-15 07:41

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

"Any white man can swear a Chinaman's life away in the courts, but no Chinaman can testify against a white man. Ours is the 'land of the free' - nobody denies that - nobody challenges it. Maybe it is because we won't let other people testify."

In most mining towns, the Chinese were often the victims of crime at the hands of white miners. "I do not think that any immigrant group suffered the abuses the Chinese did. Lynchings were not uncommon," Corbett says.

But regardless of their poor treatment, Chinese sojourners came of their own accord, with free will and rein to pursue gold and fortune. They were at first welcomed in the country, Corbett says.

"They were considered good workers and were much in demand. Most Chinese immigrants were hard workers who wanted to make something of themselves. But there was a criminal element - let's not forget that."

Indeed, in the book Corbett goes into great detail about the public impression of Chinese criminality, wanton behavior and the whorehouses of Chinatown and beyond.

|

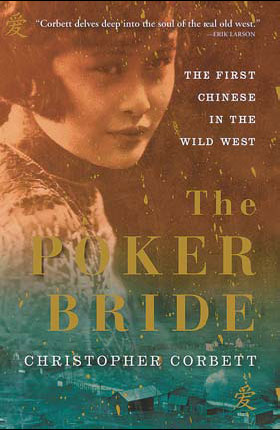

Christopher Corbett's new book, The Poker Bride, sheds new light on the life of Chinese miners during the American Gold Rush. Provided to China Daily |

He quotes Benjamin E. Lloyd, who in Lights and Shades in San Francisco documented Chinatown in detail: "Tremendous wealth and poverty existed side by side," Lloyd wrote about Chinatown. "But beneath the gold and marble veneer seethed another world populated by abused workers, exploited Chinese, alcoholics, gamblers, prostitutes, cutthroats, pettifoggers and charlatans.

"The most disastrous effects of this traffic in human flesh and blood are seen in the Chinese quarter of San Francisco - in the Chinese houses of prostitution," Lloyd writes.

This was the world into which Polly Bemis was brought to the US, and while details of her later life are numerous and well documented, Corbett pieced together much of her journey through the accounts of historians who never actually met her. In fact, there were very few first-person accounts of what it was to be Chinese in the US, because so many Chinese who made the trip were uneducated and of the laboring class.

But Polly was different. As a result of her role in Idaho folklore, more details about her life have survived than most Chinese of the time.

"I thought Polly was a good subject," Corbett says. "She puts a very real human face on an experience that both fascinates and horrifies us She is of interest to us because she is a real person who survived an experience that ought to have killed her."

While some accounts have disputed the truth of whether Polly was truly lost in a poker game, it is of historical record that she came to live with Bemis on his ranch on the banks of the Salmon River in Idaho.

In 1890 Bemis was shot and pronounced incurable by a doctor. Polly begged to differ, and nursed him to health. He married her shortly after. They lived together until the end of their lives. After his death she made two trips to town, both of which were front-page news.

"Her speech is excellent with just enough of the 'pidgin English' to make it fascinating," read one newspaper article about her visit to town in 1924. "Her memory is remarkable, particularly for dates, and her eyes twinkle as she tells jokes on herself, as she spoke of the miners not liking the coffee she made, and the way she silenced them by appearing with a butcher knife and the question, 'Why no like my coffee?'"

By this time, much of the resentment against the Chinese had faded. They had been largely absent since the Exclusion Act, and Polly was treated with kindness. In 1933, she died at her ranch. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943.

The Poker Bride paints a grim picture of the US faced by Chinese in the years leading up to the Exclusion Act, but in Corbett's thorough account of that world, he manages to document a humanity that white Americans often were blind to.

"The Chinese in the old days were remarkably resilient, patient and industrious," he writes. "Those are not clichs. The ghosts of the old Chinese - in a very real sense - haunt the American West, even today. We should never forget them."

Specials

In the swim

Out of every 10 swimsuits in the world, seven are made in China.

Big spenders

Travelers spend more on shopping than food, hotels, other expenses

Rise in super rich

Rising property prices and a fast-growing economy have been the key drivers.