Uniting writers from disparate lands

Updated: 2013-01-11 12:22

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

US President Jimmy Carter greets novelist Hualing Nieh and her husband, Paul Engle, a fellow writer, at a White House reception. Provided to China Daily |

When novelist and poet Hualing Nieh arrived at the University of Iowa's prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop in 1964, she was one of only a few international students in a predominantly American group of young writers.

She looked around at the other foreigners - from Ethiopia, the Philippines, South Korea and elsewhere - and sensed that what they needed from an education, and what they hoped to write about, were so distinct that a separate program was warranted. Many were older than their American counterparts, had been published already and were well established in their own countries. Nieh, for instance, had published seven books in Taiwan.

She turned to Paul Engle, director of the writers' workshop - who would become her husband - and suggested that, when his tenure ended, they launch a program especially for foreigners.

"What we needed was so different," Nieh told China Daily. "Paul said to me, 'Are you crazy?' I said, 'Sometimes.' And so we tried. You never succeed if you don't try."

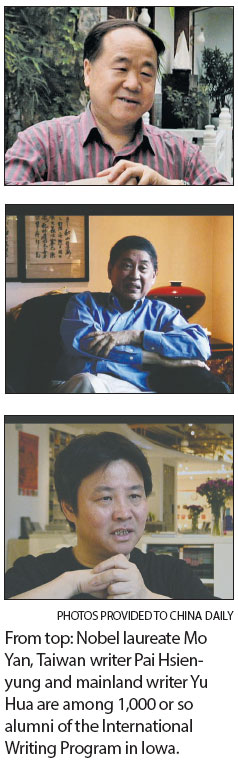

In 1967, the couple founded the International Writing Program, which has since hosted over 1,000 writers from 120 countries and regions.

Among them are Nobel Literature Prize winners Mo Yan of China (Red Sorghum) and Orham Pamuk of Turkey (My Name is Red), and Chinese novelist Yu Hua (To Live, which was adapted to a 1994 movie).

Nieh and the IWP are the subject of One Tree: Three Lives, a new documentary by Angie Chen, whose 2008 film This Darling Life was nominated for Best Documentary at the Taiwan Golden Horse Awards. One Tree: Three Lives premiered at the 2012 Hong Kong International Film Festival.

"I am a tree with roots in (the mainland) China, the trunk in Taiwan and leaves flourishing in Iowa," Nieh writes in a poem featured in Chen's film. "This is the Iowa River, and that is the Yangtze River. Where these two rivers meet is my home."

Nieh took over as IWP director for several years after Engle's 1977 retirement (he died in 1991) and now serves on the program's advisory board. She is the author of more than two dozen books, including Mulberry and Peach, which won an American Book Award in 1990 and was named one of the 100 greatest Chinese novels of the 20th century by Asia Weekly magazine, published in China.

Chen met Nieh as a teenager in Taiwan while she was attending junior high school with Nieh's daughter. Later, the filmmaker studied at the University of Iowa and became involved in the IWP as its official musician for writers' recitals. She grew close to the Nieh family.

"I deeply admire the spirit in which Paul and Hualing founded the IWP," Chen said of her decision to tell the couple's story. "I was inspired by the enormous love they had for each other, but also the enormous love they felt toward other human beings, toward humanity and world peace.

"This writing program was and is a platform for people all over the world with different ideas and beliefs to come together, fight it out among themselves to reach an understanding and ultimately take that back to their original countries. That seed is sown."

Christopher Merrill, the current IWP director, said the impact of Nieh and Engle's endeavor is far-reaching.

"They went out and made it happen," he said.

"The effect has been that for 45 years, we've hosted some of the greatest writers in the world in a truly unique environment, where the written word is taken really seriously. These writers get to know one another fairly intimately, and they also get to know the literatures of a great many countries," according to Merrill.

"Not only are there occasions for collaboration, but more to the point they have these chances to break down their stereotypes of what a Chinese writer, or an Indian writer, is, and what literature in South Africa might be about."

"They have primary contact with living writers from a diverse range of countries, and it's difficult to imagine them leaving without larger ideas of what writing really is. They leave realizing they have more in common than what divides them. That's the beauty of what they created."

In 1976, Nieh and Engle were nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for their work with the IWP.

However, the program has never been intentionally diplomatic in nature, Chen said.

"Writers are not politicians. We deal with each other as individuals and as friends. We may argue out of curiosity, but never out of animosity," the filmmaker said.

She recounted the story of an Israeli couple who at first refused to speak to a fellow IWP participant from Germany. The German writer persisted and by the end of the semester had been invited to visit the Israelis in their land.

"They got to that point because they read each others' work, and it had an effect on how they looked at him. They accepted him, and it happened very naturally. They understood each other more and more, and soon realized, 'We are writers; we are human beings.'"

In the film, Engle says: "If you are reading poetry to each other, you are not fighting each other."

In 1979, Xiao Qian became the first writer from China's mainland to join the program. That year, Nieh and Engle organized a Chinese writers' weekend, in which Xiao and about 40 writers from Hong Kong, Taiwan and the United States discussed Chinese literature.

"Everyone was so excited and overjoyed at this opportunity to talk with Chinese writers," Nieh said. "It was sensational. Everyone wanted to talk to Xiao; everyone was very welcoming."

That sense of community and connection is at the heart of IWP, according to Merrill.

"The basic idea of the program is a group of writers gathering around a table and trading stories and ideas, and breaking bread," he said.

"She is incredibly generous. It's important to remember that at the heart of all this, is a great writer who wanted to share her good fortune with writers from around the world.

"That's what writers, even at their most solitary, are doing: They are communicating with readers. That form of connection is at the heart of what Hualing, and this film, are about."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

In Photos: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

Li Na on Time cover, makes influential 100 list

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

FBI releases photos of 2 Boston bombings suspects

World's wackiest hairstyles

World's wackiest hairstyles

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Sandstorms strike Northwest China

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

Never-seen photos of Madonna on display

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

H7N9 outbreak linked to waterfowl migration

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Dozens feared dead in Texas plant blast

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Live report: 7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan, heavy casualties feared

Boston suspect cornered on boat

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|