Health

Treating myths

Updated: 2011-08-03 08:43

By Laura Nichols (China Daily)

|

Youngsters with epilepsy and their parents gather to celebrate Children's Day at a Guangzhou hospital. Chen Hui / for China Daily |

Chinese who live with epilepsy, especially those in rural areas, find more social than physical challenges arise from the disorder. But hope is on the horizon. Laura Nichols reports.

Nie Shaofei's life - a monotonous existence punctuated by "fistfuls" of pills - has been frozen in time since epilepsy forced him out of middle school and into total social withdrawal about 20 years ago.

He lets his mother, Wang Yunhuang, speak for him as he sits watching TV in the back of the family's convenience store.

Nie (whose name has been changed at his request, like other patients in the story), only interjects to say he thinks he's in his 30s and knows he can never realize his lifelong dream of becoming a police officer.

The limitations the disease has placed on his life are more social than physical, as the condition is stigmatized in China.

That's especially true in rural areas, such as in Nie's community in Beijing's northeastern suburbs.

His seizures started when he was 9 months old. So did his mother's quest for a cure. She's still looking.

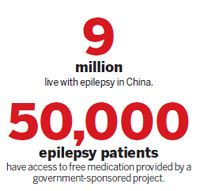

Until 2005, many rural Chinese living with the world's most common neurological disorder received minimal treatment - or none at all. About 9 million people live with epilepsy nationwide, the Beijing Neurosurgical Institute says.

Patients who admit to having epilepsy are often barred from school and are usually unable to find jobs or romance. Many around them believe the seizures are frightening or even contagious.

The government-sponsored National Epilepsy Project has led to drastic changes in rural areas since 2005. It provides free medication for 50,000 patients in 132 counties of 18 provinces.

More than 30 percent haven't experienced a seizure in about three years since they started taking medication regularly.

But this effort came too late for such patients as Nie.

Over the decades, he has undergone myriad traditional Chinese and modern Western treatments. But he still sometimes has seizures.

Wang believes her son has developed a resistance to every medicine and taking so many drugs has caused his kidney problems.

Epilepsy persists in rural areas not only because of insufficient knowledge about the condition but also because patients previously couldn't access treatment, the project's director Dr Wang Wenzhi says.

Traditional Chinese medicine has not yielded results for most patients, Dr Wang says. Few could afford medication if they could access it before the project. Many patients still forgo seeking help, because seizures remain taboo in Chinese culture, Wang says.

"(People) are afraid of seeing a seizure," he says.

"Epilepsy is not terrible. Taking medication regularly is effective."

Tong Shuiguan has overcome many obstacles arising from her disease but says she still can't accept her condition might never change.

Her lower lip trembles as she recalls how her life turned upside down in the seventh grade. She, too, was forced to drop out.

But Tong believes she's fortunate to have found a husband - especially one who's supportive, although frustrated by his wife's condition.

Tong was too afraid of passing on the disorder - which runs in her family - to the next generation to give birth. So, the couple adopted a daughter.

The stigma largely arises from the association of the disorder with "grand mal" seizures, Wang's former colleague and University of Liverpool professor Ann Jacoby says.

Also known as "tonic clonic" seizures, they often cause the patient to lose consciousness or control over bodily functions.

But seizures take various forms, she says.

Some are less obvious. Patients might act strangely - unbuttoning their clothes, for example, or muttering incoherently.

The West regards epilepsy as a treatable, clinical condition, while many in the developing world - such as China and Africa - fear it, Jacoby says.

Community members, friends and family will often forgo helping someone who's experiencing a seizure because they fear touching the person will cause them to have seizures, too.

Many believe epileptic patients' abilities are limited, which subjects the patient to the stigma of disability and helplessness.

That's why research to not only understand but also eradicate stigma through education is so important, Jacoby and Wang agree.

Yang Rongrong, a lead author of a recent Peking University study on the stigma surrounding epilepsy, says government support is crucial. It provides the consistent care that ensures patients receive proper treatment, empowering them to choose how to lead their lives.

Yang says discrimination is worse than she had imagined before conducting the study.

There is a cultural component in epilepsy myths, Yang explains, but government intervention can foster change.

"This is not the responsibility of an individual," she says. "It's the responsibility of the country."

The government project provided rural clinicians and provincial physicians with training on how to administer the right medicines and doses. County hospitals' neurologists were also trained, he says.

But many parents still fear their children will be socially excluded and avoid treatment, Wang says. That might explain why more adults than children receive medication in the countryside, he says.

Wang believes parents need to realize that getting sufficient treatment for their children is more important than shielding them from social scorn.

Nie's mother says her first priority has always been finding help for her son.

But she still worries about the toll that epilepsy has taken on him.

Nie has progressed to the point he goes outside a few times a week, but he still won't talk to anyone.

The mother says she still has hope his life will change - but only to an extent.

Nie loves children, she says, but fatherhood is out of the question.

"We just don't talk about that."

Luo Wangshu contributed to the story.

Specials

Carrier set for maiden voyage

China is refitting an obsolete aircraft carrier bought from Ukraine for research and training purposes.

Photo

Photo  Video

Video

Pulling heart strings

The 5,000-year-old guqin holds a special place for both european and Chinese music lovers

Fit to a tea

Sixth-generation member of tea family brews up new ideas to modernize a time-honored business