Enforcing trade ban can also end ivory appeal

|

| LUO JIE/CHINA DAILY |

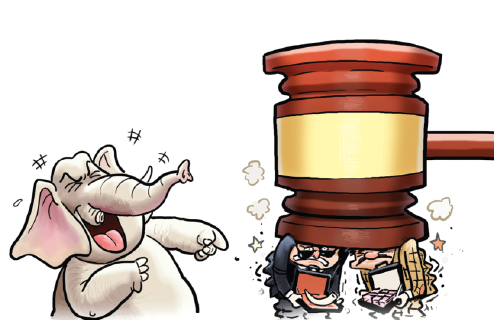

The international demand for ivory threatens to wipe out elephants within little more than a decade, since every 15 minutes or so poachers slaughter an elephant for its ivory.

An estimated two-thirds of the demand comes from China, where members of a growing middle class associate carved ivory products with luck and prosperity. The trade in ivory trinkets, chopsticks and figurines has remained legal even though the government enacted a ban on ivory imports and related products in March last year.

China has now taken a historic step to phase out the commercial ivory trade by the end of this year, a decision that has been greeted as the single biggest hope for the survival of elephants since the modern poaching crisis began.

"Ending the legal ivory trade in China-the world's largest consumer of elephant ivory-is critical to saving the species," wrote Elly Pepper of the US-based Natural Resources Defense Council, welcoming the Chinese government's decision.

Under the measures China announced at the end of December, domestic ivory carving workshops and factories will shut down by the end of March and registered traders and processors will be phased out by the end of the year.

Britain's Prince William, a prominent wildlife campaigner, said the Chinese ban was a potential turning point in the race to save elephants from extinction.

"I congratulate the Chinese government for following through on this important commitment," he said in a statement.

Beijing's action may indeed turn out to be the most important measure to preserve the species since the African elephant was first listed as an endangered species in 1989.

But many other factors are involved and experts are reluctant to predict that the future of the world's largest land mammal is now secure.

Activists have argued that the legal trade has helped to disguise the illegal trade, because it was often impossible to determine the origin of raw ivory. Although the new ban addresses that to a large extent, 40 tons of legal ivory remained stockpiled in the mainland at the end of last year, as China Daily reported, and could become a complicating factor in instituting the new ban.

Experts also believe the effectiveness of the ban will depend on strengthened measures to combat smuggling. A recent surge in demand for ivory and rhino horn in Vietnam has been linked to possible smuggling networks.

There is also still much to be done beyond China's borders to confront the extinction threat.

There is a need to deter poachers who earn a mere handful of dollars per kilo of ivory that is then sold to end-users for hundreds of times more.

That will involve more effective aid programs to improve the livelihoods of poor rural communities. But it will also demand more effective anti-poaching tactics.

Blue Sky Rescue, one of China's largest nongovernmental disaster rescue organizations, has sent volunteers to Africa to join local efforts in wildlife protection.

Meanwhile, the UK government announced late last year that it was partnering with China to train African border forces to spot and stop smugglers involved in the illicit trade in animal products.

Such measures will help reinforce the impact of the ban on the legal trade announced by Beijing.

Yet ultimately what is needed save the elephants from extinction is a change in public attitudes. The State, wildlife activists and celebrities have joined in campaigns to educate Chinese consumers about the devastating impact of the ivory trade. Now that the legal trade is being banned, the desire to own ivory should become even less respectable.

Prosperous consumers may eventually be persuaded that the most exciting way to enjoy ivory is to book an African safari and go and see it attached to a living elephant.

The author is a senior editorial consultant for China Daily UK.