Economy

US divide 'not easy' to bridge

Updated: 2011-07-29 08:01

By Brian Faler (China Daily)

|

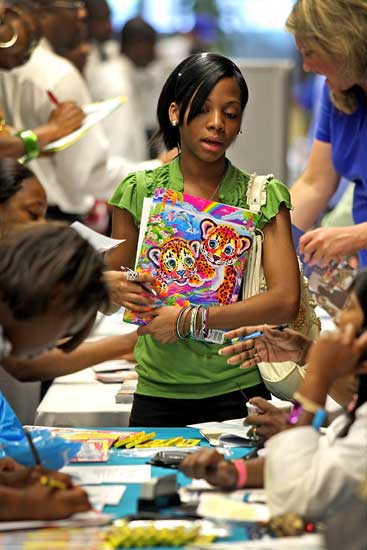

A job seeker speaks with representatives at an employment fair in Chicago in the United States. Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC (S&P) is considering downgrading the US government's credit rating, which will add more woes to the largest economy in the world. Tim Boyle / Bloomberg |

Agreement necessary on both debt and deficit, ratings expert warns

WASHINGTON - David Beers says he sees a "political divide" in the United States that won't be any easier to bridge with time.

As the London-based managing director of sovereign credit ratings at Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC (S&P), Beers will help determine whether the US government's credit rating will be downgraded as a result of the political battle over raising the debt limit.

His company has gone beyond competing credit-rating agencies to say that it isn't enough for lawmakers to agree to lift the government's $14.3 trillion debt ceiling. Congress and the White House also must agree to a deficit-reduction package to avoid a downgrade in the government's AAA credit rating.

In an interview this week in Washington, Beers said he views the debt limit fight as a test of lawmakers' willingness to tackle the deficit.

"For us, the issue is not the debt limit - it's the underlying fiscal dynamics," said Beers, who has been rating governments for the company for 20 years.

"It's not obvious to us that this political divide that is proving so difficult to bridge is going to be any more bridgeable three months from now or six months from now or a year from now."

He said he didn't know when an S&P committee would decide whether to cut the credit rating. "Depends on events," he said.

Downgrade impact

A decision to cut the government's credit rating would likely increase US Treasury rates by 60 to 70 basis points over the "medium term", raising the nation's borrowing costs by $100 billion a year, JPMorgan Chase & Co's Terry Belton said.

It could also hurt the broader economy by increasing the cost of mortgages, auto loans and other types of lending tied to the interest rates paid on Treasury securities.

On Wednesday, the markets showed little concern about the debt ceiling, as seen in 10-year Treasury note yields hovering around 3 percent, below the average of 4.05 percent over the last decade, and the average of 5.48 percent when the US was running budget surpluses between 1998 and 2001.

Meanwhile, House and Senate leaders were trying to advance deficit reduction packages that would clear the way for a vote on the debt ceiling increase that the Treasury Department says must come by Aug 2.

The threat of a downgrade has made S&P a target for critics chafing at demands from a company that blessed the mortgage-backed securities that led to the financial crisis.

S&P's critics

|

|

An April report by Senator Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat, and Senator Tom Coburn, an Oklahoma Republican, concluded the credit agencies "weakened their standards as each competed to provide the most favorable rating to win business and greater market share. The result was a race to the bottom".

In an interview, Levin said he views those faults as conflict of interest issues that are separate from S&P's sovereign ratings work, which he declined to criticize. "My gut tells me that they're calling it as they see it and, hopefully, they're not impacted by their previous failures," Levin said.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, a Nevada Democrat, took a different view. "I wish they had made a few demands when Wall Street was collapsing," said Reid. "They were silent then. Maybe they're trying to get more energized."

July warning

At issue is a warning the company issued on July 14 that there is a 50 percent chance S&P would downgrade the government's credit rating within three months if lawmakers didn't approve a "credible" deficit reduction package as part of a plan to raise the debt cap.

It was the latest in a series of demands from the company over the past year. In April, S&P said there was a one-in-three chance it would downgrade the government within two years; in October, it said lawmakers had as many as five years to address long-term deficits.

In its July report, the company said: "We believe that an inability to reach an agreement now could indicate that an agreement will not be reached for several more years."

Critics say S&P is misreading the political dynamics in Washington and that it shouldn't engage in political prognosticating.

"If we fail to increase the debt ceiling, they have every right to take the US down as many notches as they want," said Jared Bernstein, former economic adviser to US Vice-President Joe Biden.

"I don't look to S&P for political analysis", he said, and "their job is not to try to do political crystal-ball gazing. Their job is to assess the reliability of US debt."

Bernstein added: "Nothing fundamental has changed in the ability of the US government to fully meet its debt obligations."

Bloomberg News

Specials

Wen pledges 'open' probe

Design flaws in the signal equipment led to Saturday's fatal high-speed train collision, authorities say.

Turning up the heat

Traditional Chinese medicine using moxa, or mugwort herb, is once again becoming fashionable

Ciao, Yao

Yao Ming announced his retirement from basketball, staging an emotional end to a glorious career.