Wang Ling-chi: Fearless fighter for civil rights

Updated: 2014-08-29 13:03

By Chang Jun in San Francisco(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

Wang Ling-chi, a renowned civil rights activist for Asian-American communities, said he never gives up on things he believes are right. He led Chinese for Affirmative Action, fighting for equal education rights for children of new immigrant. Chang Jun / China Daily |

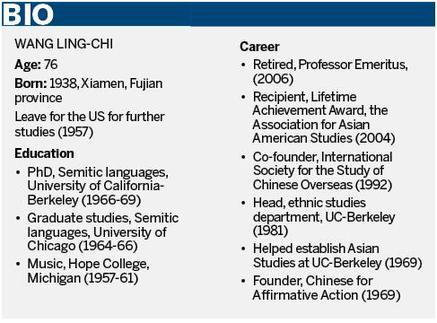

Wang Ling-chi's name resounds in San Francisco and beyond. On the one hand, he excels in academic achievement as an expert on Asian-American history and the founder of the ethnic studies program at the University of California-Berkeley. On the other hand, he is even more well-known as a minority civic activist who has been serving his fellow Chinese wholeheartedly for more than 40 years.

Wang, 76, said he never gives up on things he believes are right and does not mind being misunderstood along the way. "I'm so used to criticism and confrontation," said Wang.

Most recently Wang was identified by the Chinese-American community as an articulate supporter of Senate Constitutional Amendment No 5, or SCA-5, a proposal that many Asian-American families regard as promoting racial discrimination.

The proposed amendment proposes to allow such public education institutions as the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) systems - and even K-12 schools - to use race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin as a consideration in enrolling students or hiring employees.

Seemingly in agreement with the measure, Wang sat at a town hall meeting as a panelist on March 2 in Cupertino, saying measures should be taken to change the current university admission policy, which he thought put too much emphasis on SAT scores and grade-point averages.

"Merit should also include leadership, volunteering, special talent," he said, adding that he thought there was a lack of diversity on UC campuses.

"As beneficiaries of affirmative action, we Asian Americans should remember to give chances to everyone, including those from the socio-economically disadvantaged families. In other words, when drinking water, don't forget its source," said Wang.

However, Wang's remarks were misconstrued as proof of his "betrayal" of Asian Americans' core values and drew fire. "Look at our so-called community leader," yelled someone in the audience pointing a finger at Wang. "Can we believe that he would stand up for us and fight for our rights?"

Wang has stood up and fought for minority immigrants since 1969 when he and several community activists and students established Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA) to advocate on behalf of Chinese Americans who are "systematically denied equal opportunity in many sectors of society", as the CAA creed puts it.

CAA achieved social changes in the civil rights sector. It challenged social norms to advance equality, created coalitions that bridged traditional boundaries and prioritized the needs of the Chinese community's most marginalized members.

In the education sector alone, CAA fought for and won the right for thousands of Chinese-speaking students to attend public schools in the lawsuit Lau v. Nichols in 1974.

The civil rights case, brought byChinese Americanstudents inSan Franciscowho hadinsufficient English skills, claimed they did not receive special assistance in school due to their inability to speak English.

Finding that the lack of linguistically appropriate accommodations effectively denied the Chinese students equal educational opportunities, theUS Supreme Courtin 1974 ruled in favor of the students.

Wang also spent five years in the 1980s hounding the chancellor of the University of California system to get him to revise admissions policies which Wang called "discriminatory and biased against Asian-Americans applicants" and apologize in public for the past wrongs.

Wang's investigation uncovered a set of "secret" admission policies in practice, which was not only used to break down SAT verbal scores to filter applicants, but also raised the GPA threshold for automatic UC admission from 3.7 to 3.9.

"Both measures were targeting Asian Americans," said Wang.

In 1984, Wang called on the chancellor to revise the policy. "The school denied it, so I called national and local media and continued my fight until one day in 1989, the chancellor sent the vice chancellor to meet with me and asked what it would take to get me to stop," Wang recalled.

"Two conditions: One, these policies I've defined as discriminative should be dropped; two, the chancellor and the university should publicly apologize to Asian Americans for their wrongdoing," Wang said.

" 'The first, consider done,' replied the vice-chancellor right away," said Wang, adding the chancellor admitted the admission policy was wrong and apologized for the harm it had brought to the Asian American families.

Asked how he was able to endure five years of arduous battle against an institution he worked for, Wang said "because I knew I was right and I really don't give up when I believe I'm right".

Wang said he could have dedicated his whole life to doing research on the Old Testament, Semitic languages and Middle Eastern culture if he hadn't taken an African American studies course in the mid-1960s. Wang had just received his bachelor's degree in music and composition from a small college in Michigan and was a graduate student at the University of Chicago when he chose to take courses on Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, Black pioneers in the civil rights movement whose message inspired him.

"The two activists have both influenced me deeply," said Wang. "I just don't believe that when people are being unjustly oppressed that they should let someone else set rules for them by which they can come out from under that oppression."

Wang visited San Francisco in 1966 and made a stop at Chinatown. "It had the densest population in that congested neighborhood," said Wang.

"Because of their very limited English, [immigrants] ended up in Chinatown and a lot of problems arose such as housing, employment, gambling, street gangs and drugs," said Wang.

Wang could not help but associate the mess in Chinatown with the ghetto neighborhoods of the Blacks, and realized that Chinese Americans, just like other minority groups, had been systematically and historically denied equal opportunities.

Wang decided to transfer from Chicago to the University of California-Berkeley, a Mecca in the 1960s for activists eager to bring change to society through the civil rights movement. In 1969, Wang received his doctorate, started teaching at Berkeley, initiated CAA and got actively involved in community affairs.

Although much progress has been made, Chinese Americans still have a long way to go before eventually removing all racial barriers and becoming mainstream, said Wang.

"Fundamentally, serious racial problems still persist in the US," he said.

junechang@chinadailyusa.com

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

Chinese float gives joy at Macy's parade

Chinese float gives joy at Macy's parade

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

6 things you should know about Black Friday

6 things you should know about Black Friday

Visa change may boost tourism to the US

Visa change may boost tourism to the US

China's celebrity painters

China's celebrity painters

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China, US fight terror on the Internet

How to give is focus of philanthropy forum

China, US diverge on approaches to nuclear energy

China's local govt debt in spotlight

Macy's looks to appeal to more Chinese customers

Clearer view of Africa called for

Cupertino, California council is majority Asian

BMO Global Asset Management Launches ETFs in Hong Kong

US Weekly

|

|