|

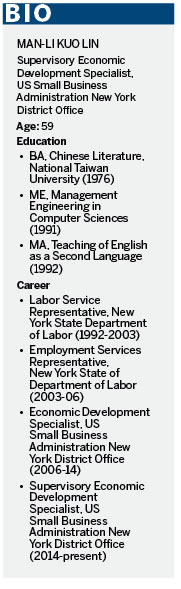

Man-Li Kuo Lin is supervisory economic development specialist at the New York District Office of US Small Business Administration. Lu Huiquan / for China Daily |

For Man-Li Kuo Lin,it always goes back to helping people.

Lin, a small-business specialist for the US government, once taught English to more than 100 Chinese immigrants at a time - for free.

Lin's path to her current job involved a lot of hard work and making it through difficult times.

The story for the Taiwan native starts when she joined a Buddhist societyat National Taiwan University.

"At first, I wanted be a nun, but they (the temple)said I couldn't disconnectwith the mortal world," Lin said.

She graduated with a bachelor's degree in Chinese literature and a minor insecondaryeducation in 1976, and then began working as a teacher. In 1983, she came to the United Stateswithher husband, who was pursuing a master's degree in Ohio, and returned to Taiwan in 1984.

Lin said that the relationship turned violent, and to escape domestic violence, she returned to the US in 1990, pursuing a master's degree at Long Island University in New York.

It was tough for her as the single mother of a young son.

"I would feel very fortunateif I couldsleepfourhours a day," she said. In order to support her education, she had toworkduring the day at the school's student activity center and then study at night.

The hard work paid off.In two years, she got two master's degrees:one in management engineering in computer science and another in the Teachingof Englishas a Second Language (TESOL).

"Buddhism talks about endurance, hard work and focus," she said, "If there were no Buddhism, I would not make it through the day."

She saw an ad in a newspaper that the New York State Department of Labor was recruiting, and she applied.

There was a vacancyinFlushing, aneighborhoodin Queenswherea lot of Chinese-speaking immigrantslive, so she was assigned there,firstapprovingunemploymentbenefits and thenhelping people find jobs.

"I see many rich but unhappy people," Lin said. "To me, helping others makes me happy."

She also said that working for a government agency makes it "easier for you to do good deeds".

Shequicklydiscovered a problem: Many job seekers, although they were excellentworkers, couldn't speak English. Some did not knowthey could receive benefits from the governmentwhen unemployed.

Along with the languageissues werecultural ones.

"Americans who are born here are generally more willing to express their gratitude," she said. "They are very expressive, while Chinese immigrants are not," she said, "Little by little, others turned unwilling to help Chinese."

So she volunteered to teach English to Chinese immigrants in 1995.After her daytime work, she lectured on English to Chinese immigrants at night and on Sundays. She designed all the curricula; found places to hold the classes; and was not paid during her 13 yearsof teachingin Flushing.

More than 100 attended her lectures each time, and "I had to wear a speaker on my waist," she said. "I was just like a troubadour."

Her class materials, for which she consulted about 20 books, have beenpublished as the book English Phonetics.

She also had a 15-minute show ata local Chinese radio station about jobinformation and tips. Her tips later were summarized and published in a book calledEnglishResume Writing and Interview Skills,published in 2002.

In 2006, she joined the US Small Business Administration (SBA) as an economic development specialist, whereshe helpedsmall businesses in Asian communities comply with regulations and seek business opportunities.

In August 2014, she was promoted to her current position - supervisory economic development specialist at the New York District Office of US Small Business Administration. She is now helping small businesses in14 counties throughout New York City, Long Island and the downstate counties of Dutchess, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, Sullivan, Ulster and Westchester.

Working at the SBA"is really in accordance with my previous job as someone who helps others find jobs," she said."Due to language barriers and other factors, many new immigrants cannot find good jobs. So, it is actuallybetter for them to start their own businesses,and if their businesses are successful, they can hire more people."

According to a 2011 SBA survey,99 percent of employers in New York state are small businesses with fewer than 500 employees, and those employersmake up 51 percent of the state's employment and factor into 59.7 percent of the state's exports.

In New York City, there are 67,000 small businesses, and the Chinese communityhas the largest number of immigrant small business owners, with more than 6,500, according to the Fiscal Policy Institute.

"My biggest concern is that many people don't know how businesses shouldworkhere," Lin said.

Lin listed some problems she has encountered:Chinese are less willing to use credit cards, so many business owners do not have a credit recordto winloans. Even if they could have loans, they are still more willing to ask their families and friends for funds, "but you simply cannot get your business big this way", she said.

Chinese business owners sometimes would prefer to follow what others have been doing, even though it is illegal,instead of heeding government regulations."Once one [illegal behavior] is found, everybody will be punished. The fine could be a six-digit number," she said.

Lin looks to make changes through her small-business lectures, of which she gave more than 250 in 2013, telling owners how to finance their businesses, to the latest government policies and methods towin government contracts.

"I have to deliver the same content againevery three months, because every three months, we have a wave of new people, and they still need guidance," she said.

She also noticed a pressing need for more representation of the Chinese community and a unified leadership.

When she wasworking at the Department of Labor, she once asked why there was no Chinese version of documents whileEnglishand Spanish versions were both offered.

"They said it was because Chinese people don't vote," she said. "That's a very pragmatic reason."

The voting rates for Asian Americans, including Chinese Americans, are historically lower than other ethnic groups, according to the Pew Research Center.

Many Chinese neighborhoods still lack organization. She told China Daily that she sometimes couldn't evenfind an effective community organization to help coordinate SBA's events.

"Let's go back to the language issue; the government does want the Chinese community to have a unifiedidea. Simplified Chinese or Traditional Chinese; Mandarin or Cantonese ... they simply cannot cater to every one's taste, right?" she said.

Lin is hopeful about the next generation. She lectures Chinesestudents at Columbia Universityon small business every month.

"Oh, I am so inspired by these children," she said. "They have started their own businesses while they are still at college."

Lu Huiquan in New York contributed to this story.