|

|

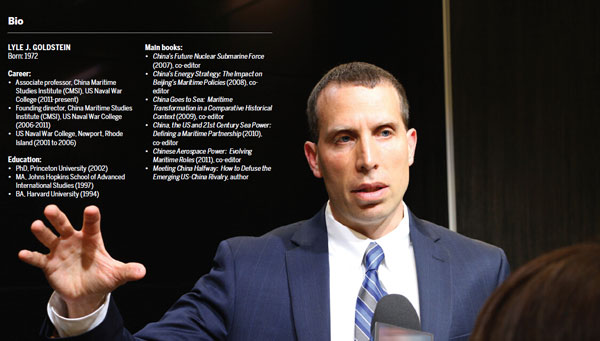

Lyle Goldstein, China scholar at the US Naval War College, says he tries to play a role in US-China relations by calming tensions. Weihua Chen / China Daily |

Lyle Goldstein was a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in 1996 when the Taiwan Strait crisis broke out. China conducted missile tests in the waters there to send a signal to the then-Taiwan leader Lee Teng-hui who tried to move away from the One China Policy. The US, under then-President Bill Clinton, sent two aircraft carrier battle groups to the region to show its support for Taiwan.

Goldstein, then 25, told himself, "Gosh, this is such an important issue, the rise of China, and how it (United States) will get along with China."

The young man, who had studied Russian and lived in Russia, was attracted by China but felt unsure if he could start China studies at such a "late" age.

Mentors

Literally the first day he started his PhD at Princeton University in the fall of 1997, he talked to students and faculty about beginning Chinese.

"Looking around the world; I thought the biggest question facing international politics was going to be between the US and China. It was obvious in 1996 and 1997," said Goldstein, now an established China scholar and an associate professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute in the US Naval War College based in Newport, Rhode Island.

He spent the summers of 1997 and 1998 in Beijing, studying the language and China, and returned in the summer of 1999 for his PhD research at Tsinghua University.

At Princeton, Goldstein studied with several China scholars such as Lynn White III and Gilbert Rozman. His Chinese progressed by studying with Perry Link, who specializes in modern Chinese literature and language.

Goldstein still remembers clearly that White always looked closely at how Chinese were thinking about issues and brought Chinese into the classroom for discussion. "That was great, and I feel I learned a lot," he said.

He described Rozman as being very interested in cooperation and how to get different countries to work together.

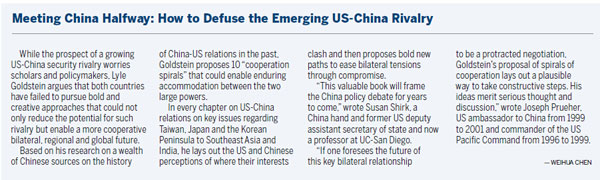

Another of Goldstein's professors was Aaron Friedberg, whose books, especially the one A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia often spread a pessimistic view of China's rise. They contrast sharply with Goldstein's 2015 book Meeting China Halfway: How to Defuse the Emerging US-China Rivalry, in which he proposes that China and the US should both compromise to reduce their tensions.

Goldstein thought Friedberg, who served from 2003 to 2005 as deputy assistant for national security affairs in the office of Vice-President Dick Cheney, was useful to him because he was good at asking the big and fundamental questions.

"I don't agree with him. I think China's approach to the world is quite reasonable," he said, citing the fact that China has not used force for more than 30 years and doesn't have major foreign bases, and even in the maritime domain, China is not such a challenge.

At Princeton, he worked on a dissertation examining nuclear strategy and found that while people like Chinese leader Mao Zedong talked big and bombastic and threatening, they became more moderate after they developed the bomb. That, according to Goldstein, could offer some insights into today's North Korea.