A Chinese relic finds a new home in US

Other details reveal the house's history. There are chalk writings on the wood walls from the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) period. Red diamond-shaped paper painted with the Chinese character double "Xi" or "happiness" has faded to white. It is attached to the door of a bedroom where a newlywed couple stayed.

Among the 700 objects the house came with are intricate and rusted hairpins and a porcelain urinal.

"It's a labor of love and story of serendipity," Wang said. "It's a story of many, many people and institutions who supported this project."

Obtaining the house for the move to Salem was "pretty accidental," said Nancy Berliner, who was PEM's curator of Chinese and East Asian art. In 1996, she was going to villages in China doing research on vernacular architecture. When she was in the village of Huang Cun, she went by Yin Yu Tang but nobody was home.

Later, she returned to the village, and members of the Huang family were there discussing what they should do with the house because all the family members had moved to bigger cities. Nobody was living in it or planned to live there.

Jokingly, they asked Berliner, "Do you want it?"

"I thought at the moment that the house would be fantastic for the museum in America," she said."I realized that the way for Americans to really understand Chinese culture and Chinese people was through everyday residential architecture."

"The way to understand the people of another culture is through their home, how they live," she said.

The local cultural relics administration was seeking a US cultural institution to help increase international awareness of traditional architecture from its region. An agreement was established with PEM to move the house to the US and to help protect and promote the region's local architecture.

It took seven years from when Berliner first saw the house to when it was opened to the public in 2003 at PEM. No part of the process was easy - negotiation, dismantlement, transportation, preservation and reassembly.

Museum officials declined to provide the cost of the Yin Yu Tang project, but according to a New York Times story right before the house was opened, people close to the project at the time said that it could easily cost $15 million, including fees paid to the local Chinese government and money to restore a 1531 shrine and three other local houses.

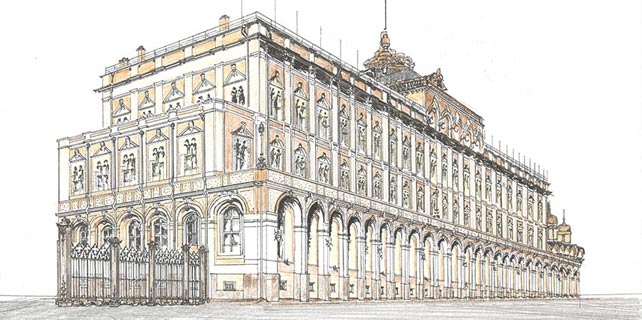

Nineteen crates holding the house were transported by truck through the mountains to Shanghai.

"The village, at the time, was in a remote area in China. There wasn't even a proper road for the trucks to get out. So we actually had to build the road in order to facilitate the process," said Wang.

From Shanghai, the crates embarked on a months-long journey to New York via the Panama Canal.

They were taken to a large warehouse 30 miles from Salem and unpacked: 2,735 wooden components, 972 stones and more than 60,000 bricks and tiles.

Conservation work soon began with carpenters and stone masons traveling from Anhui province where the house was located to make repairs, including joining old deteriorated wood to new wood and patching broken stones. The project also involved historic house preservation specialists in the US.

"It was a huge international collaboration and an opportunity for both sides to learn from each other," said Wang.

Yin Yu Tang consists of two halls separated by a central courtyard. The South hall was considered more prestigious because its rooms get more sunlight and thus more yang energy - nature's masculine principle. The downstairs of each hall was considered better than the upstairs.