Heavy Brew

|

|

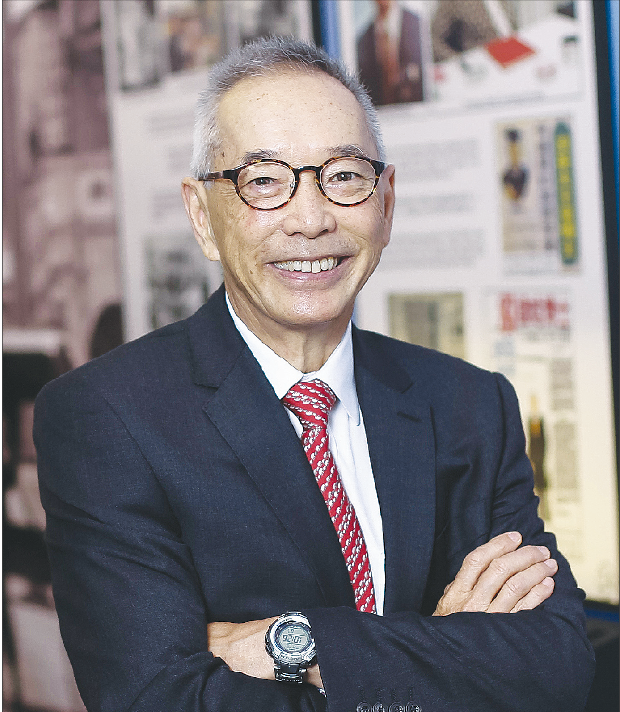

David Ho Sue San has a shrewd assessment of market economies. One `example is his company's dominance in Africa. Provided to China Daily |

Herbal tea maker turned major Malaysian generic drugmaker is poised to find a treatment for stroke

While every pharmaceutical player hopes to discover the next wonder drug, in reality it takes decades and huge investments to create a blockbuster product.

Hence, to suggest that a generic drug manufacturer in Southeast Asia could produce the world's first treatment for stroke raises eyebrows. After all, even big pharma companies have failed to achieve this.

But that is exactly what might happen if David Ho Sue San, managing director of Hovid, wins a pharmaceutical claim for tocotrienol, a palm-sourced vitamin E compound that has shown positive neuroprotective properties in local clinical trials.

There is currently no specific treatment for stroke. So, should Hovid obtain from the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the coveted recognition for Tocovid — the commercial form of the vitamin E compound — as a novel drug, a billion-dollar market could potentially open up for the company.

Hovid's headquarters are on the outskirts of Ipoh, the capital of northwestern Perak state. It has been Malaysia's largest generic drug exporter over the past 30 years.

Typical of generic drugmakers, Hovid does not advertise or brand its products. It does, however, sell 400 products in more than 40 countries and owns 1,500 market authorizations worldwide - a feat that very few pharmaceutical players in Asia can match.

Hovid's origins date back to a traditional herbal tea created by Ho's father, Ho Kai Cheong, a Chinese sinseh (traditional herbalist). The herbal tea helped tin miners overcome flu in postwar Malaya.

Originally sold from a roadside stall, the 24-ingredient beverage, named Ho Yan Hor — meaning ‘everybody can have good health' in Cantonese — became a household name in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand.

Inspired by his father's passion for healthcare, Ho pursued a degree in pharmacy.

While working as a research pharmacist at Wyeth Pharmaceuticals in the United Kingdom, his father asked him to take over the business.

"Then in his 70s, my dad could no longer manage the business on his own. I thought it was a pity to let a 40-year-old heritage go," Ho recalled.

Ho Yan Hor was a single-product business with turnover below 1 million ringgit ($234,000) when Ho joined in 1980.

To expand the product line, Ho mooted the idea of entering the generic drugs market, as he had the manufacturing experience and the company could afford to purchase a sizable land bank.

Soon, Ho Yan Hor was reborn as Hovid - an amalgam of the family surname and Ho's first name.

With profits from Ho Yan Hor's modest turnover and a small bank loan as capital, Ho set his sights on expansion.

One of his first tasks was to repackage the company's flagship herbal tea.

He invested in an automatic packing line, and the decades-old practice of sun-drying tea leaves made way for a modern dryer.

On the pharma front, rather than fight domestic and foreign incumbents in capital-intensive large therapies, Ho focused on generic drugs with unique formulations and dosages.

Competition was less intense in this segment, and Ho had an edge due to his experience. Hovid entered the Malaysian pharmaceutical market with film-coated antibiotics.

"The standard sugar-coated tablet would take 10-20 hours to process. Film-coated tablets are faster to produce (and save cost). But there were no film-coating machines then," Ho said.

His experience at Wyeth had taught him how to achieve the same outcome using a sugar-coating machine. This led to the company's first major tender win.

Hovid's competency in formulation and testing led to patented technologies in drug-delivery systems, antibiotics in dispersible tablet form, film-coated analgesics and softgel capsules, and effervescent tablets.

In 2016, Hovid spent 45 million ringgit on a production facility in Ipoh, adding to its two existing plants.

With automated storage and retrieval systems, the new centralized distribution center handles a higher volume of stocks with more efficient inventory management and distribution.

"We expect it to increase tablet and capsule production by 30 percent. Additionally, it meets the higher cGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice) standards … for us to penetrate the Australian, European and American markets in the future," Ho said.

The company's latest crown jewel is the Penang-based Attest Research. The bioequivalence (BE) center conducts human clinical trials on generic products to prove their biological equivalence to the originator product.

Traditionally, clinical trials are outsourced to dedicated BE centers or hospitals.

As of last year, Hovid's development pipeline included 137 products, including over-the-counter and prescription drugs, dietary supplements, traditional remedies and disinfectants, cosmetics and food products.

"BE centers are unique in Southeast Asia. Hovid has the distinction of being the only pharmaceutical manufacturer in Malaysia to have its own BE center," he said.

A key factor in Hovid's success is Ho's shrewd assessment of market economies. One good example is the company's dominance in Africa.

In the 1980s and 1990s, when Hovid's Malaysian rivals were fighting for the local market, Ho focused on Africa. This was long before the supporting data to confirm the continent's market potential was public knowledge.

Consultancy McKinsey & Company valued Africa's pharmaceutical industry in 2013 at $20.8 billion, up from $4.7 billion a decade earlier.

"I could see that the growth in US and Europe was slowing down and the market was saturated. Asia is very competitive and unpredictable; finding sustained growth is tough," Ho noted.

"Unfortunately, or fortunately, African countries have never had a ‘dragon' or ‘tiger' boom or bust. They just grow quietly but steadily. Last year, Ethiopia's growth was 10 percent."

Today, 60 percent of the firm's export revenue comes from more than 20 countries in Africa.

Since Hovid went public in 2005, Ho's ownership in the company has been progressively reduced. But he is unlikely to let go any time soon, given that he is on the threshold of a breakthrough for tocotrienol.

More than 10 completed and ongoing clinical studies conducted in collaboration with higher learning institutions suggest several unique benefits, including neuro-cells protection and reduction of stroke-induced injuries.

Some of the results have been published in leading peer-reviewed journals, such as Stroke and Nutrition Journal.

By virtue of Malaysia's position as the world's biggest source of palm oil, from which tocotrienol is extracted, Hovid sits on a virtual goldmine. Still, there is a long way to go before the company hits this sweet spot.

Sold as Tocovid in around 30 countries as a dietary supplement, tocotrienol cannot claim to prevent, treat or cure illnesses without FDA certification.

"We have a lot of work to do in terms of addressing regulatory approval, clinical studies and consumer awareness," Ho said.

A clue to Ho's motivation may be found in the Ho Yan Hor Museum, which he opened last year to document how a humble tea stall evolved into one of Malaysia's most valuable pharmaceutical companies.

Pharmaceuticals and herbal tea may seem worlds apart, but as they say, the apple does not fall far from the tree.

"I share the same ideals as my father. Like him, I hope to bring something of my own invention that can give the world better health," Ho said.