Riding the big wave

Updated: 2012-09-21 08:57

By Cecily Liu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Right fit

Another Chinese company that is championing a localization strategy is Bosideng, a Chinese down apparel manufacturer that recently opened its first international flagship store in London.

Despite being a Chinese brand, Bosideng's UK collection is the work of well-known British designers Nick Holland and Ash Gangotra, who have previously worked with Oasis frontman Liam Gallagher and his label Pretty Green.

Most of the items sold in Bosideng's London store are manufactured in Europe, using raw materials from 15 different suppliers across Italy, Turkey and Portugal.

Only 7 percent of the products are manufactured in Bosideng's Chinese outlets and even these items are quite different from the Bosideng China collection.

"We've created that twist of inventiveness," says Jason Denmark, director of retail operations, Bosideng UK, as he points to a red down coat, recognizable as Bosideng at first glance, but distinctive for having added shoulder pieces and elbow pads in tweed - a popular material in British fashion.

He says that the tweed fabric is sourced in Europe, shipped to China, stitched onto the coat and then shipped back to the London store. This emphasis on European quality has made Bosideng's store in central London popular with customers from around the world.

Sharing NVC and Bosideng's philosophy is SAIC Motor Corp, which acquired British car manufacturer MG Rover in 2005.

Although much of the manufacturing shifted back to China following the acquisition, research and development, design and final assembly are still done in the UK to satisfy local customer demand.

"Our job in the design studio is to make sure that we follow the trend globally, we follow the quality globally, and we know what the taste of the trend is globally," says Martin Uhlarik, SAIC's UK design director.

Challenges ahead

Most of the Chinese businesses are still in the early days of investing in Europe, and are still learning to overcome challenges like cultural differences and unfamiliarity with a new market.

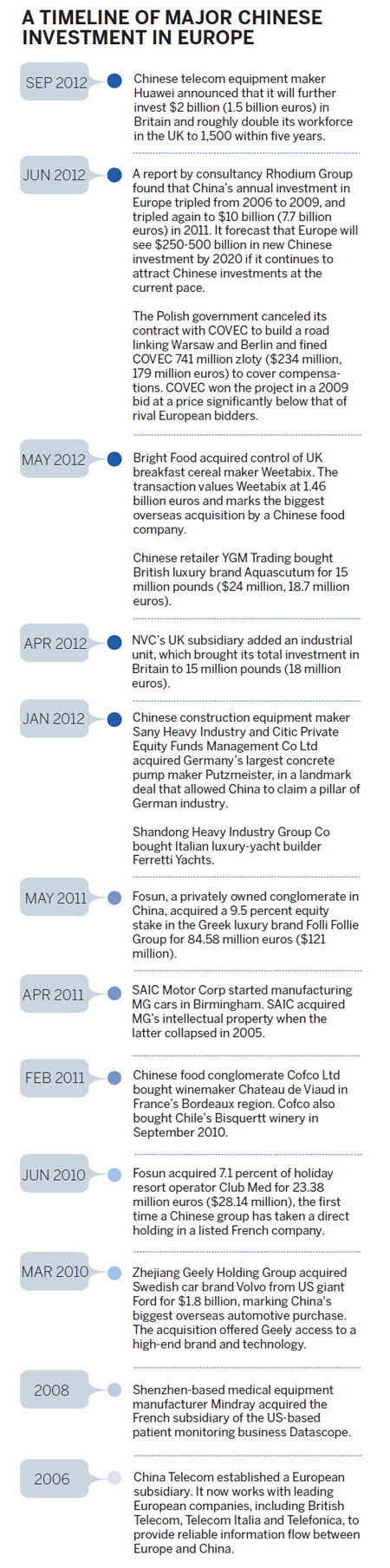

One recent example where such challenges led to controversy is China Overseas Engineering Group's construction of a highway project linking Berlin and Warsaw, which failed to materialize.

COVEC won the contract in 2009 with a bid significantly below its European competitors' prices, but the company realized that it had underestimated its costs soon after construction began, according to the Chinese online publication Caixin.com.

Labor unrest and a strike by its Polish sub-contract workers on payment-related issues added to the Chinese company's woes.

The Polish government canceled its contract with COVEC in June 2011 and handed COVEC a bill for 741 million zloty ($234 million, 179 million euros) to cover compensation and fines following what it claimed were the contractor's mishandlings of the project.

Although COVEC's failure is a high-profile case that highlights the challenges of miscommunication and poor planning, similar challenges can be experienced by almost every Chinese business on a day-to-day basis.

"Cultural differences can exist even in basic areas such as accounting and bookkeeping," Parr says.

As an advisor, Parr says that his team will continue to advise clients after a deal is completed, so as to help both parties better communicate with each other.

|

||||

Although such restrictions apply to Chinese and local businesses alike, Chinese businesses find it a bigger challenge as they often need to employ Chinese speakers to liaise with their head offices and provide services to Chinese clients in Europe.

In the UK, for example, every company can apply to sponsor their workers' work permits, but their requests are often not granted.

Xue Haibin, a partner in the London subsidiary of the Chinese law firm Zhonglun W&D, says that he had to let go of a trainee lawyer last year when Zhonglun W&D failed to secure a work permit for the employee.

Xue says that because only a fixed number of work permits for trainee lawyers are issued each year, his firm lost out to bigger law firms that can pay employees higher salaries.

While applicants for work permits need to secure a job that pays a minimum annual salary of 20,000 pounds ($32,000, 24,000 euros) under British immigration law, Xue says that some firms pay trainee lawyers up to 50,000 pounds.

"Bigger law firms take up a disproportionate amount of the annual work permit quota," Xue says. While the annual limit of non-EU workers entering the UK in both 2011 and 2012 is 20,700, sector specific quotas are not public information.

Since Zhonglun employs staff members who can advise clients on Chinese law and speak Chinese fluently, recruiting becomes a huge challenge if it only searches in Britain's domestic or EU job markets.

A further challenge that Chinese companies are yet to realize is the need to build a good image in the eyes of their European partners and their local communities, especially if they acquire a local business.

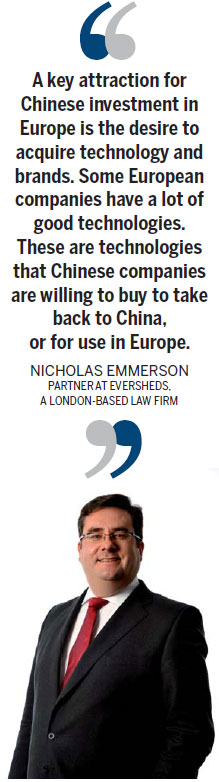

"If the Chinese company takes the key assets back to China after the acquisition and fires all the workers from the European company, they will send out a message that the Chinese are not long-term partners," Emmerson says.

Once this poor reputation is established, European businesses may become reluctant to sell their assets to Chinese bidders even if they offer higher prices than rival bidders from other countries, he says.

"European businesses, especially private businesses, have a good relationship with their employees and with the region of its operations.

"Right now there are not enough case studies of Chinese investment in Europe to create an impression on what kind of investors they are. It's like a typhoon, you are told its coming but how strong it is, whether it changes direction or just fades away, we don't know," he says.

Li Xiang in Paris contributed to this story.

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 09/21/2012 page1)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|