China and innovation: some myths to dispel

Updated: 2012-10-26 09:56

By Bhaskar Chakravorti (China Daily)

|

||||||||

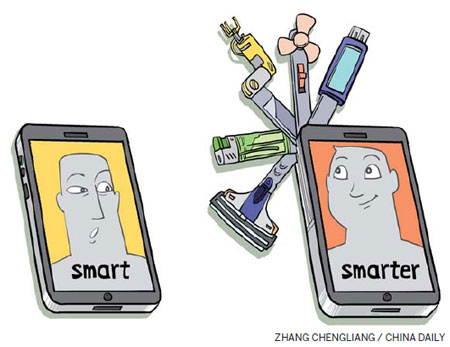

Just as how the US leads in technology, so too can China

On a recent to visit to China to speak at the World Economic Forum's Summer Davos in Tianjin, I was struck by a palpable sense of urgency. Catching up with US GDP was no longer the only burning issue; China, it was said, needs to close the gap with the US on innovation. I agree, but some myths about innovation in China need to be dispelled. I have heard five mentioned most frequently.

1. There is no innovation, only piracy and imitation.

2. The Chinese approach to innovation is too top-down and State-led, and real innovation only comes from the bottom-up from entrepreneurs.

3. Protection of intellectual property rights is weak, discouraging innovation.

4. China's Asian education model emphasizes rote learning, with a narrow emphasis on science, technology, engineering and mathematics; innovation can only flourish in environments that encourage exploration, critical thinking and a broad education in the liberal arts tradition.

5. In a globalized economy, sustaining innovation requires investments in international markets; China's brand and soft power abroad is weak and dated.

Each of these beliefs, mostly held by China skeptics, is a statement about China's innovative spirit compared with that of the US, the world's benchmark. Of course, the reality is more nuanced.

There is more to China's nascent innovation model than is suggested by this cardboard-cutout view, and it is time to dispel it.

On myth 1, regarding piracy and imitation, it is sobering to note that one theory has it that the word "yankee" originates from the Dutch word for "pirate". America got its start by pirating or, at the very least, imitating inventions from the Old World. The Industrial Revolution was anchored by the steam engine and railways which were, by no means, American innovations. These laid the foundations for revolutions that the US did indeed lead.

The lesson: most innovation begins with a modicum of imitation, and even some piracy. Imitation is often the launchpad for the most disruptive of innovations. Many Chinese "imitations", such as Alibaba, Tencent or Sina Weibo, have proven that they have moved far beyond being mere copies of US inventions. Each is solving problems uniquely relevant to Chinese businesses and consumers. It is essential to evolve and continuously innovate; otherwise you are destined to remain trapped near the bottom.

With myth 2, regarding State-led innovation, the State does indeed play a disproportionate role in championing that cause. The government wants China to be "in the ranks of the innovative nations" by 2020, with many goals: Research and development funds to reach 2.5 percent of GDP by 2020; average R&D input for large and medium-sized industrial enterprises to be 1.5 percent of revenues and at least 43 employees responsible for R&D for every 10,000 employees.

No doubt, this is a very top-down approach to fostering innovation. The typical Silicon Valley entrepreneur would shudder at this degree of State intervention. But consider where the entrepreneur would be if the US government had not funded the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that gave birth to the Internet. Where would the modern consumer be without NASA and spillovers from Cold War era defense spending that gave rise to many familiar inventions? Where would we all be without mobile technologies, developed at Bell Labs, funded by government contracts and a regulated monopoly, and without the World Wide Web, a product of European public funding of CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research?

Foundational innovations such as the Internet and mobile technologies have low returns on investment, high risk and ultra-long payback periods. It is essential that the state step in to make these investments, because the private sector will not do so. However, once the foundations are laid, it is essential to have a competitive bottom-up ecosystem that encourages people and enterprises to chase opportunities and that sets in motion a process of creative destruction. This dynamic cannot be mandated by the state.

On myth 3, regarding intellectual property rights protection, such measures are a mixed blessing for innovators. Patents encourage innovation but block them, too. For example, Google entered into talks with Apple to settle patent disputes over Android-based smartphones, while Google Motorola Mobility filed a patent lawsuit against Apple following recent patent lawsuits by Apple against Samsung. Much of this is a turf war between giants rather than intellectual property protection for innovating in the best interests of consumers. At the forum in Tianjin, Linus Torvalds, the software engineer responsible for the Linux kernel, suggested that China's weaker enforcement of intellectual property may, in fact, be a boon for "open" innovators. Open innovation spreads the investments and risk of innovating across a large base, but also leverages a broader base of expertise. Arguably, China's weaker intellectual property protection could create a climate conducive to such innovation. But a balance needs to be struck between open access to intellectual property and protecting it. With no protection, innovation will stall, because investors need returns on their investment.

On myth 4, concerning Asian education, there are two separate, connected issues. One relates to the education process and the other to the subjects emphasized. A key to the US lead in innovation is that it has moved away from rote memorization and test-taking as the central tenets of teaching in the best schools and colleges. These institutions promote a spirit of exploration, critical thinking and creative problem-solving, which, in turn, is more likely to produce more innovative thinkers. On the second issue, one can argue that liberal arts curricula develop a multi-dimensional intelligence.

In other words, a valid argument underlies myth 4. However, the US system has some severe deficits, which, ironically, are being filled by many with Asian education credentials. A recent US Department of Commerce report on "The Competitiveness and Innovative Capacity of the United States" highlights a growing gap in the education of science, technology, engineering and mathematics in the US. According to the Kauffman Foundation, a quarter of the US science and technology companies founded from 1995 to 2005 had a foreign-born CEO or lead technologist. In Silicon Valley, 52 percent of start-ups were founded by an immigrant. Without the education gap being filled by immigrants whose early education is mostly Asian, the innovativeness of the US itself would suffer. The Chinese approach clearly has its strengths. The danger is that if you do not then expose these students to other disciplines and encourage critical thinking, they may not have breadth and will fail to blossom into creative problem solvers and risk takers.

On the fifth myth, the weakness of soft power, China has indeed invested in winning hearts and minds in international markets through trade, infrastructure investments, Confucius Institutes and the media. But the strategy has many critics, one of them the man who coined the term "soft power", Joseph Nye of Harvard University. But even he cites a BBC poll suggesting that China's strategy has produced a positive influence in much of Africa and Latin America. Recent studies from the Peterson Institute of International Economics suggest that the renminbi bloc is displacing the dollar bloc in East Asia. Despite several unresolved issues such as balance of trade, labor and maritime or territorial disputes, China's influence in Africa, Latin America and East Asia is growing faster than that of the US. These are the world's fast-growing regions with a burgeoning middle-class. When Chinese innovations look for inputs or consumers and they turn to these markets, they are likely to have as much chance as well-known US brands, and perhaps even a better chance.

The Chinese model of innovation obviously needs work, but there is a tendency by many in the US to be dismissive about its innovative capacity. I believe this is naive. In many ways, China is following in the footsteps of the US in coming up the curve. It will add the uniqueness of its own experience and approach and create a new hybrid model of innovation to address unmet needs in China and abroad.

In fact, I will go a step further and dispel one more myth by saying that the US and the Chinese models are not mutually incompatible, but enhance one another. Each could benefit by borrowing a page from the other.

The author is senior associate dean, the Fletcher School, Tufts University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily. Contact the writer at Bhaskar.Chakravorti@tufts.edu

(China Daily 10/26/2012 page9)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|