Shipwreck detective on trail of Senegal's slave trade secrets

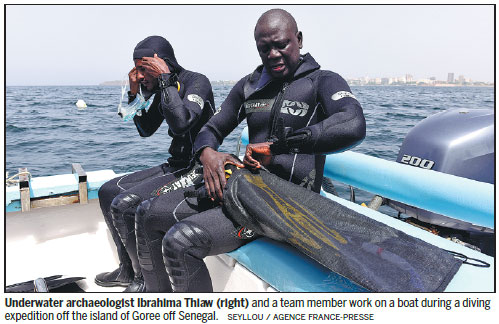

DAKAR, Senegal - Staring out to sea on a flawlessly sunny day, underwater archaeologist Ibrahima Thiaw visualizes three shipwrecks once packed with slaves that now lie somewhere beneath Senegal's Atlantic waves.

He wants more than anything to find them.

Thiaw has spent years scouring the seabed off the island of Goree, once a West African slaving post, never losing hope of locating the elusive vessels with a small group of graduate students from Dakar's Cheikh Anta Diop University.

Goree was the largest slave-trading center on the African coast between the 15th and 19th century, according to the United Nations cultural agency UNESCO, and Thiaw believes his mission has a moral purpose: to heal the open wounds that slavery has left on the continent.

"This is not just for the fun of research or scholarship. It touches us and our humanity and I think that slavery in its afterlife still has huge scars on our modern society," he said, pulling on a wet suit and rubber boots for the day's first dive.

Thiaw believes his native Senegal, with its own long and violent history of trade in human flesh, could tell the world more about how modern capitalism was founded on violence inflicted on African bodies.

"The Atlantic slave trade was the foundation of our modernity, so this is a history for all mankind," he added, referring to the so-called "Triangular Trade" of human labor for consumer goods between Africa, the Americas and Europe.

Thiaw, who originates from a rural area of Senegal but went on to study in the United States, had become known for his research into slaves' living conditions on Goree island when he was approached three years ago by the US National Park Service and National Museum of African American History and Culture to find a west African base for their "Slave Wrecks" project.

Around 1,000 slave shipwrecks are believed to dot the seabed between Africa and the Americas, according to "Slave Wrecks" researchers, but few have been found.

Thiaw complains that there is a lack of interest within Senegal for his work, especially at the institutional level where, he said, there was "very little funding for research".

"I think in Senegal there's a lot of silence surrounding the issue but I think the time is ripe that we start to teach our students and our children how to respect people of different or lower status, slave caste," he said.

Agence France-presse