WWII POW's trauma revealed in exhibition

|

|

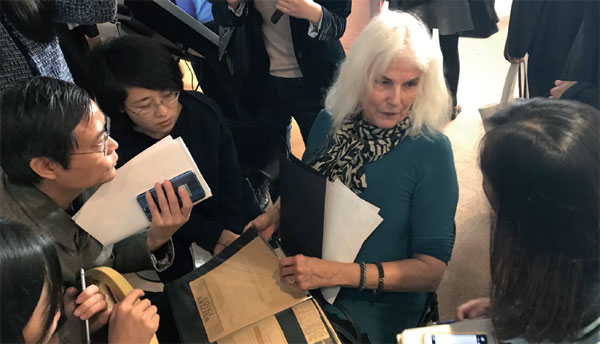

Jackie Huss Hallerberg, daughter of Walter Huss, a US POW at the Mukden camp, shares stories about her father’s war experiences with media members at the opening ceremony of the exhibition. LINDA DENG / CHINA DAILY |

"OK FLYING HOME LOVE." The four-word telegram came from 22-year-old Walter Huss in 1945 after nine months in solitary confinement in a Japanese POW camp with an untreated broken foot.

What Huss also brought back home at the end of World War II was trauma and survivor's guilt that would trouble him for the rest of his life.

He never got over the loss of his fellow crew members and he continued to hold onto the identity of a POW until his last days, said Jackie Huss Hallerberg, his daughter. Huss died three years ago at the age of 90 in Santa Rosa, California.

"There are many generations of people who have been affected by World War II, the Vietnam War, any war. But it doesn't just end when that war ends or when that person passes away," said Hallerberg, a poet-teacher in Sonoma County, California.

At a recently opened exhibition titled "Forgotten Camp" in San Francisco, she showed some of her father's artifacts, including medals, telegrams, historic photos, family letters and his camp number. She said it was her job to tell the stories now.

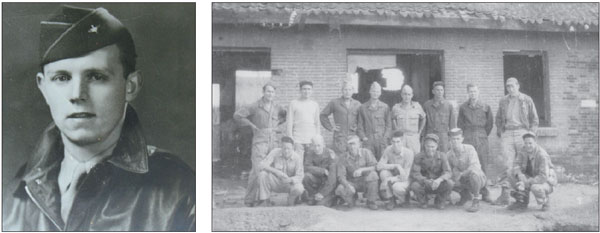

Born and raised on a farm in Ohio, Huss enlisted and became a tail-gunner on a B-29 nicknamed "Humpin' Honey". The airplane and its nine-man crew was hit by a Japanese Kamikaze in December 1944 while on a mission to bomb a Japanese "plant", which was actually an illegally unmarked Allied POW camp run by the Japanese Army in Mukden (today's Shenyang), China.

"The last word he heard from the pilot was 'jump' and then he and another gunner in the back were blown from the plane," said Hallerberg. "They didn't open the parachute but somehow they fell to the ground and immediately they were captured and put in the camp."

The notorious camp held more than 2,000 Allied prisoners, 1,200 of them Americans, from November 1942 to August 1945 when the Soviet Union liberated them.

Huss and another 13 prisoners were held in a separate house next to the main camp because the Japanese thought they might have information that could be useful against the Allied forces.

The 14 prisoners never visited the main camp but they managed to communicate with them by exchanging notes hidden in a hollowed-out wooden spoon.

"My dad was afraid to write the first message, because they didn't know if the Japanese guards were tricking them. But later they found out there were thousands there," said Hallerberg.

The camp was specially built to intern Allied POWs from the Pacific Theater. The Japanese researched each of their prisoners and put the highest-ranking officers and those with technical backgrounds in this camp, according to Gao Jian, a researcher at the "9.18" Historical Museum in Shenyang.

All of the prisoners, except those seriously ill, were forced to hike about six miles every day to work at a Japanese military factory, she said.

In the small house, Huss and his fellow prisoners suffered more from mental anguish as the Japanese tried continually to intimidate them.

"He was young. From my dad's smile in the photos, he looks vibrant, happy and joyous. Because of the experience, especially the confinement, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)," said Hallerberg.

"He was always on hyper alert," she recalled. "He used to listen to the radio all night long - that's characteristic of PTSD because you want to remain vigilant, like you don't know what's going to happen."

A lot of times, she was frustrated that he still carried his identity as a prisoner - "1887", his camp number. "He would even have his license plate made with 'POW1887,'" she said.

After he got back to the US, Huss went to visit the families of all seven fallen crew members and told them about the last moments with their sons.

One crew member he especially mourned was Charles Krueger, a flight engineer. "He had twin sons born while they were overseas, so he never got to meet his sons," said Hallerberg.

"'Why not me instead of Charles?' said my dad, because he wasn't married at that time," she said. In the 1990s, Huss reached out to the twin sons who were in their 50s.

"My dad never got over that. I can't tell you how many times I heard about the twin sons. I think survivor guilt works that way - it's hard to erase," said Hallerberg.

She said her father was able to cross the divide and accept the Japanese people after some 40 years. Once Huss was invited to talk about the war to his grandson's class at school and there he met a Japanese-American boy and talked with him in Japanese.

"I'm proud of him," Hallerberg said. "It took him a long time, though."

liazhu@chinadailyusa.com

|

|

Left: Walter Huss in 1944 before he was captured by the Japanese Army. Right: Walter Huss (first row, second from right) and other B-29 airmen, all part of the 58th bomb wing group, posed in front of the small house where they were held outside the Mukden Allied POW camp, on Sept 1, 1945. PHOTO COURTESY OF JACKIE HUSS HALLERBERG |