|

|

[Photo provided to China Daily] |

Luc de Clapiers, an 18th-century French essayist, said, "The most absurd and reckless aspirations have sometimes led to extraordinary success."

That is true. Even at the bridge table, a reckless line of play can work out well, when the cards are favorably distributed. However, in newspaper columns and classes, recklessness is costly.

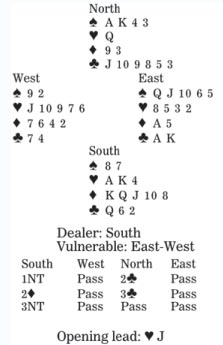

In this deal, for example, how should South play in three no-trump after West leads the heart jack to dummy's queen?

North's sequence showed game-forcing values, at least one four-card major and five-plus clubs. (Probably East did well not to overcall two spades. North would have doubled, and the contract could have been defeated by two tricks. But if North-South had still ended in three no-trump, a spade lead would have been lethal. Also, East might have doubled three no-trump, which would have asked for an unusual lead. Typically, West would have led his shorter major.)

South starts with five top tricks: two spades and three hearts. It looks easy to play on diamonds to get those four extra winners. But if the defender with the ace wins the second round of the suit and switches to spades, declarer probably won't see his hand again until it is too late.

Instead, South should lead a club at trick two. Suppose East wins and shifts to the spade queen. Now declarer must win in the dummy and lead a diamond-not a reckless club. If East takes this trick, South gets two spades, three hearts and four diamonds. If East ducks, South wins in his hand, cashes the heart ace, then leads his club queen to take two spades, two hearts, one diamond and four clubs.

Raymond Zhou:

Raymond Zhou: Pauline D Loh:

Pauline D Loh: Hot Pot

Hot Pot Eco China

Eco China China Dream

China Dream China Face

China Face