New York - In a discovery sure to fuel an old debate about our evolutionary

history, scientists have found a remarkably complete skeleton of a 3-year-old

female from the ape-man species represented by "Lucy."

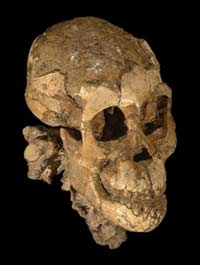

This photo provided by the journal Nature,

shows the skull of a three-year-old Australopithecus afarensis found in

Ethiopia. Scientists have discovered the remarkably complete skeleton of

the 3-year-old female from the ape-man species represented by 'Lucy.'

[AP Photo] |

The remains found in Africa are 3.3 million years old, making this the oldest

known skeleton of such a youthful human ancestor.

"It's a pretty unbelievable discovery... It's sensational," said Will

Harcourt-Smith, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History in New

York who wasn't involved in the find. "It provides you with a wealth of

information."

For one thing, it gives new evidence for a contentious feud about whether

this species, which walked upright, also climbed and moved through trees easily.

The species is Australopithecus afarensis, which lived in Africa between

about 4 million and 3 million years ago. The most famous afarensis is Lucy,

discovered in Ethiopia in 1974, a creature that lived about 100,000 years after

the newfound specimen.

The new find is reported in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature by

Zeresenay Alemseged of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in

Leipzig, Germany; Fred Spoor, professor of evolutionary anatomy at University

College London, and others.

The skeleton was discovered in 2000 in northeastern Ethiopia. Scientists have

spent five painstaking years removing the bones from sandstone, and the job will

take years more to complete.

Judging by how well it was preserved, the skeleton may have come from a body

that was quickly buried by sediment in a flood, the researchers said.

"It's a once-in-a-lifetime find," said Spoor.

The skeleton has been nicknamed "Selam," which means "peace" in several

Ethiopian languages.

Most scientists believe afarensis stood upright and walked on two feet, but

they argue about whether it had ape-like agility in trees.

That climbing ability would require anatomical equipment like long arms, and

afarensis had arms that dangled down to just above the knees. The question is

whether such features indicate climbing ability or just evolutionary baggage.

The loss of that ability would suggest crossing a threshold toward a more human

existence.

Spoor said so far, analysis of the new fossil hasn't settled the argument but

does seem to indicate some climbing ability.

While the lower body is very human-like, he said, the upper body is ape-like:

_The shoulder blades resemble those of a gorilla rather than a modern human.

_The neck seems short and thick like a great ape's, rather than the more

slender version humans have to keep the head stable while running.

_The organ of balance in the inner ear is more ape-like than human.

_The fingers are very curved, which could indicate climbing ability, "but I'm

cautious about that," Spoor said. Curved fingers have been noted for afarensis

before, but their significance is in dispute.

A big question is what the foot bones will show when their sandstone casing

is removed, he said. Will there be a grasping big toe like the opposable thumb

of a human hand? Such a chimp-like feature would argue for climbing ability, he

said.

Yet, to resolve the debate, scientists may have to find a way to inspect

vanishingly small details of such old bones, to get clues to how those bones

were used in life, he said.

Bernard Wood of George Washington University, who didn't participate in the

discovery, said in an interview that the fossil provides strong evidence of

climbing ability. But he also agreed that it won't settle the debate among

scientists, which he said "makes the Middle East look like a picnic."

Overall, he wrote in a Nature commentary, the discovery provides "a veritable

mine of information about a crucial stage in human evolutionary history."

The fossil revealed just the second hyoid bone to be recovered from any human

ancestor. This tiny bone, which attaches to the tongue muscles, is very

chimp-like in the new specimen, Spoor said.

While that doesn't directly reveal anything about language, it does suggest

that whatever sounds the creature made "would appeal more to a chimpanzee mother

than a human mother," Spoor said.

The fossil find includes the complete skull, including an impression of the

brain and the lower jaw, all the vertebrae from the neck to just below the

torso, all the ribs, both shoulder blades and both collarbones, the right elbow

and part of a hand, both knees and much of both shin and thigh bones. One foot

is almost complete, providing the first time scientists have found an afarensis

foot with the bones still positioned as they were in life, Spoor said.

The work was funded by the National Geographic Society, the Institute of

Human Origins at Arizona State University, the Leakey Foundation and the Planck

institute.