British scientists build a model gut

(AP)Updated: 2006-11-11 16:55

London - British scientists have built what they say is the world's first artificial stomach: a shiny, high-tech box that physically simulates human digestion.

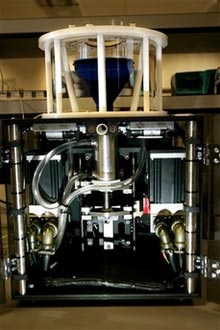

The artificial gut, designed in Norwich's Institute of Food Research, is seen during a presentation in Norwich, England, October 20, 2006. [AP]

|

"There have been lots of jam-jar models of digestion before," said Dr. Martin Wickham of Norwich's Institute of Food Research, the artificial gut's chief designer, referring to the beakers of enzymes typically used to approximate the chemical reactions in the stomach.

Wickham's patented artificial gut is a two-part model that is slightly larger than a desktop computer. The top half consists of a funnel in which food, stomach acids and digestive enzymes are mixed. Once this hydration process is finished, the food gets ground down in a silver metal tube encased in a dark, transparent box.

Software sets the parameters of the artificial gut -- how long food remains in a particular part of the stomach, predicted hormone responses at various stages, and whether it is an infant or adult gut.

Unlike previous gut models, Wickham's model incorporates the physiological elements of digestion, including the stomach contractions that break up food and move it along the assembly line of human digestion.

The artificial gut is already attracting commercial attention.

One company wants to use it to test whether a biscuit can release a specific nutrient in the small intestine. Another group wants to determine if soil contaminants, which could potentially be swallowed by children playing outside, get absorbed by the human body.

The model gut's focus on the physical and chemical reactions that take place in the stomach promises to provide a more detailed understanding of food structure and its impact on digestion.

"This is an important tool that will allow us to understand what happens in the gut," said Dr. Peter Ellis, a biochemistry expert at King's College in London, who was not connected to the project.

Other artificial stomach models have largely neglected the connection between food structure and digestion, according to Ellis. "This model is important because it gets the science of digestion right," he said.

By understanding how food gets processed in the gut, and in which part of the stomach nutrients get absorbed, researchers may be able to develop foods designed to manipulate the digestive process, a strategy that would have broad implications for public health.

For instance, knowing how quickly glucose gets absorbed into the bloodstream could potentially help treat diabetes.

"Our knowledge of what actually happens in the gut is still very rudimentary," said Wickham, "but we hope that this model can help fill in some of the blanks."

Some experts say any artificial gut has inherent limitations.

"The stomach is an extraordinarily complex organ, so you cannot create a model that will undertake all of these functions," said Dr. Stephen Bloom, head of metabolic medicine at Imperial College in London, who was not involved in the project.

Still, Bloom said that looking at issues such as the breakdown of food and the role of enzymes in a model stomach is valuable.

"There are a number of questions that are very difficult to study in real life that could more easily be answered in the laboratory," he said, noting that using human volunteers to collect information about digestion is usually a costly and uncomfortable process.

With a capacity about half the size of an actual stomach, the artificial gut can "eat" roughly 24 ounces of food. To date, the most substantial meal it's enjoyed is vegetable soup.

"It's so realistic that it can even vomit," adds Wickham.

The model gut, which was funded by the British government, was built at a cost of approximately $1.8 million. Wickham and his colleagues are currently negotiating with about a dozen companies regarding future projects for the gut.

|

||

|

||

|

|