Scientists map gene of STD parasite

(AP)Updated: 2007-01-12 06:41

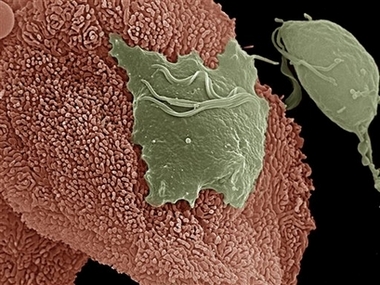

WASHINGTON - The tiny parasite undulates under the microscope like some creature from a sci-fi movie, but this one is all too real, latching onto the sexually unwary with tentacle-like probes. Now scientists have mapped the genes of the nasty little bug that causes one of the world's most common, and arguably least recognized, sexually transmitted infections, one with the tongue-twisting name of trichomoniasis.

"There are a huge number of people infected out there, but they don't know it so you don't know it," warned Dr. Jane Carlton, a parasite specialist who led the four-year effort by The Institute for Genomic Research to crack the bug's genome.

The work is published in Friday's edition of the journal Science.

Most sexually transmitted infections are caused by viruses or bacteria. A microscopic, single-celled protozoan named Trichomonas vaginalis causes this one.

The good news: "Trich," as it's short-handed, is easily curable, with a drug called Flagyl. The bad news: Many people go undiagnosed and thus continue spreading trich, plus the parasite is starting to develop resistance to the drug.

Both men and women can be infected, although trich is more common in women. But men usually suffer no symptoms, while about half of women do, reporting such problems as vaginal itching and a fishy-smelling frothy discharge.

During pregnancy, trich can cause premature birth or low-weight babies. It's linked to pelvic inflammatory disease.

But trich's real threat is that it quietly increases women's vulnerability to HIV, by altering the lining of the vagina so that it's easier for the AIDS virus to sneak in. Trich also seems to increase the chances that people who already have HIV spread it, enhancing that virus in different ways.

"It is a bad actor," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which funded the genome work.

The genetic mapping "is a very strong step in the right direction with regard to a parasite we still have not fully appreciated," he added.

The genome - which turned out to be 10-fold larger than researchers had predicted - highlights this bug's predatory nature, says Carlton, now at New York University School of Medicine.

First, it shifts from the shape of a pear to flatten and cover as much of the vaginal surface as possible. Then it sends tendrils under that surface to latch on. And then it gobbles up the vagina's good, anti-infective bacteria even as it secretes proteins that can erode holes in cells in the vaginal lining.

"We think it's a very voracious parasite," Carlton said.

|

||

|

||

|

|