Science and Health

How far do your sneeze and cough go? Experts study

(Agencies)

Updated: 2011-01-10 16:29

|

Large Medium Small |

SINGAPORE - Ever wondered how far your sneeze goes? Or if you can stop germs from spreading by cupping your mouth with your hand when you cough?

|

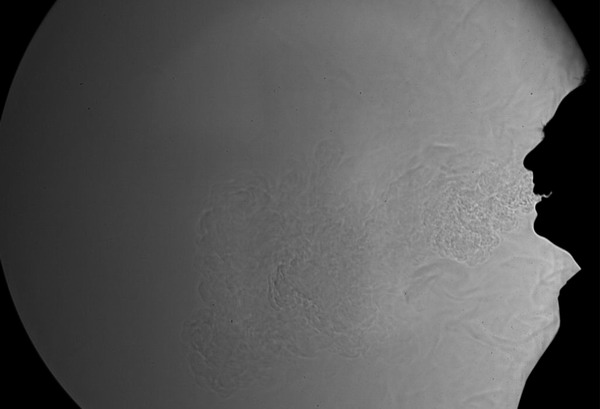

An undated still image shows the exhaled airflow, or plume, produced by a laughing person in this handout photo. With a giant mirror and high-speed camera, scientists in Singapore are trying to find out how airborne transmission of flu viruses takes place, or if it happens at all. The equipment allows them to observe real-time a person's spray of minute liquid droplets when coughing, sneezing, laughing and talking, and they hope the results can be used to make better guidelines for infection control. [Photo/Agencies] |

With a giant mirror and high-speed camera, scientists in Singapore are trying to find out how airborne transmission of flu viruses takes place, or if it happens at all.

The equipment allows them to observe real-time a person's spray of minute liquid droplets when coughing, sneezing, laughing and talking, and they hope the results can be used to make better guidelines for infection control.

"It's really to inform infection control teams, because there is controversy now about which pathogens, e.g. flu, are airborne and if so, how significant this route is compared to others, such as direct contact," said team leader Julian Tang, a virologist and consultant with Singapore's National University Hospital.

While it is likely a flu sufferer can infect others by coughing or sneezing, little is known about the distances a cough or sneeze travels and the volume of air -- and viruses -- packed into it.

Are flu viruses transmitted whilst airborne? Which is more dangerous: coughing or sneezing, or even laughing?

Infection control guidelines are mostly based on modelling studies and expert estimates, not hard scientific data.

In their S$1.08 million (US$833,000) study, funded by the National Medical Research Council of Singapore, Tang and colleagues designed a large concave mirror, akin to those used in astronomical telescopes.

Along with a camera that can capture up to 250,000 frames per second, the scientists can observe the aerosol, or spray, produced by a cough or sneeze across the mirror.

Beware laughing, singing

Using volunteers, Tang and his colleagues will study the velocity and distance of exhaled airflows, or plumes, produced by coughs and sneezes, and even laughing, crying, singing, whistling, talking, snoring and breathing.

"We will be studying these other forms of plumes, where possible, as all forms of exhaled jets have the potential to carry infectious agents over greater distances," Tang said.

They will evaluate interventions such as coughing into a loosely clenched fist, a tissue and different types of face masks to see how effective they are in containing airflows.

"What people do every day, we can visualise in real-time. Studying intervention is very important because we want to know how effective they are," Tang said.

"This may have budgetary implications when planning for the next pandemic."

With better knowledge of airflows, the scientists hope to make improved recommendations for infection control, such as how far apart to place hospital beds and quarantine measures to be taken in a place found to be housing a person with an airborne infection, such as measles, flu and drug-resistant tuberculosis.

From images seen so far, whistling and laughing appear to spread infection very effectively.

"Laughing produces a surprisingly strong, diffuse, exhaled plume, and I suspect that singing (especially trained operatic singing) will produce an even stronger, more penetrating plume," Tang said.

"However, whether they will lead to infection and disease depends on many other factors, such as virus survival and host immune responses - which other teams are studying."