Scientists find right stuff for life on Mars

|

|

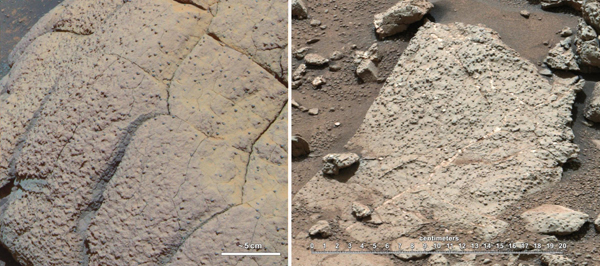

A set of images compares rocks seen by NASA's Opportunity rover and Curiosity rover at two different parts of Mars, in this NASA handout photo. On the left is " Wopmay" rock, in Endurance Crater, Meridiani Planum, as studied by the Opportunity rover. On the right are the rocks of the "Sheepbed" unit in Yellowknife Bay, in Gale Crater, as seen by Curiosity. [Photo/Agencies] |

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - Seven months after NASA's rover Curiosity landed on Mars to assess if the planet most like Earth had the ingredients for life, scientists have their answer: Yes.

Analysis of powdered samples drilled out from inside an ancient and once water-soaked rock at the rover's Gale Crater landing site show clays, sulfates and other minerals that are all key to life, scientists told reporters at NASA headquarters in Washington and on a conference call on Tuesday.

The water that once flowed through the area, known as Yellowknife Bay, was likely drinkable, said Curiosity's lead scientist John Grotzinger, who is with the California Institute of Technology.

The analysis stopped short of a confirmation of organics, which are key to most Earth-like life. But with 17 months left in the rover's primary mission, scientists said they expect to delve further into that question. Science operations currently are suspended because of a computer glitch, which is expected to be resolved this week.

Whether or not Mars has or ever had life, it should have at one time at least had organic compounds delivered to its surface by organic-rich comets and asteroids. Finding places where the organics could have been preserved, however, is a much trickier prospect than finding the environmental niches and chemistry needed to support life, scientists said.

In May, following a one-month interruption of radio communications caused by the positions of Earth and Mars, scientists plan to drill a second hole into the Gale Crater rock to look for organic compounds.

"If there was organic material there, it could have been preserved," said David Blake, principal investigator for Curiosity's Chemistry and Mineralogy, or CheMin, experiment.

A lack of organics, however, would not rule out the Yellowknife Bay site as suitable for life, scientists added.

"You don't have to have carbon present in a geological environment that's habitable in order to have microbial metabolism occur," Grotzinger said.

Some micro-organisms on Earth, for example, can feed on inorganic compounds, such as what are found inside rocks.

"There does need to be a source of carbon somewhere, but if it's just CO2 (carbon dioxide), you can have chemoautotrophic organisms that literally feed on rocks and they will metabolize and generate organic compounds based on that carbon," Grotzinger said.