Forecasting sun storm havoc

|

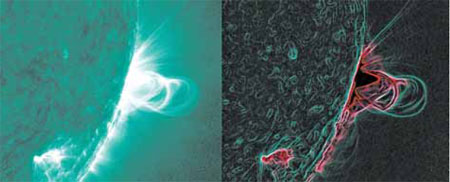

Auroras appeared over Whitehorse, Yukon, in September 2012, caused by a coronal mass ejection on the sun, above. Nasa, via Associated Press David Cartier, SR. |

|

Magnetic loops on the sun, captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory on July 8, 2012. NASA / SDO / Goddard Space Flight Center |

In 1859, the Sun erupted, and on Earth wires shot off sparks that shocked telegraph operators and set their paper on fire.

It was the biggest geomagnetic storm in recorded history. The Sun hurled billions of metric tons of electrons and protons whizzing toward Earth, and when those particles slammed into the planet's magnetic field they created spectacular auroras of red, green and purple in the night skies - along with powerful currents of electricity that flowed out of the ground into the wires, overloading the circuits.

If such a storm struck in the 21st century, some telecommunications satellites high above Earth would be disabled. GPS signals would be scrambled. And electrical grids could fail, plunging a continent into darkness.

Scientists say it is impossible to predict when the next monster solar storm will erupt - and whether Earth will lie in its path. What they do know is that with more sunspots come more storms, and this autumn the Sun is set to reach the crest of its 11-year sunspot cycle.

Sunspots are regions of turbulent magnetic fields where solar flares originate. Their ebb and flow have been observed for centuries, but only in the past few decades have solar scientists figured out that magnetic fields within the spots can unleash the bright bursts of light called solar flares and the giant eruptions of charged particles known as coronal mass ejections.

Experts are divided on the earthly consequences of a cataclysmic solar eruption, known as a Carrington event, for the British amateur astronomer who documented the 1859 storm.

A continentwide blackout would affect many millions of people, "but it's manageable," said John Moura of the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, a nonprofit group founded by utilities to help manage the power grid. Most of the grid could be brought back online within a week or so, he said.

Others are more pessimistic. They worry that a huge and well-aimed eruption from the Sun would cause not only the lights to go out, but would also damage transformers and other critical components of the grid. Some places could be without power for months, and "chronic shortages for multiple years are possible," according to the National Research Council, the leading science research group for the United States.

Still, this sunspot cycle has been quieter than most. And even if the Sun unleashes a huge burst, as it did last July, the odds are that it will head harmlessly in another direction into the solar system. Only rarely does a giant solar blast fly directly at Earth.

Yet just as a hurricane-fueled surge hitting New York City at high tide during a full moon is rare, rare is not impossible.

"There's always the chance of a big storm, and the potential consequences of a big storm has everyone on the edge of their seats," said William Murtagh, program coordinator for the Space Weather Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The most studied, unambiguous example of the Sun's ability to snarl power grids occurred on March 13, 1989, in Quebec. In the early-morning hours, a solar storm generated currents in the transmission wires, tripping circuit breakers. Within minutes, a blackout stretched across the province. Power was restored later that day.

Canada was hit again a few months later, when another solar storm was blamed for computers shutting down at the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Mr. Moura's organization put out a report last year saying that utilities would have enough warning to disconnect the grid and protect the transformers.

The dangers will not go away after the solar maximum - the period of heaviest solar weather - has passed. Even when quiet, with few sunspots, the Sun can still produce a giant eruption.

Solar flares, traveling at the speed of light, arrive at Earth in less than 8.5 minutes and can drown out some radio communications. But it is the coronal mass ejections - in which billions of metric tons of electrons and protons are disgorged and accelerate to more than a million and a half kilometers per hour - that cause more worry.

The ejected particles, which generally take two or three days to travel the 150 million kilometers from the Sun to Earth, never hit the surface; the planet's magnetic field pushes them aside.

But then they are trapped in the field. The back-and-forth sloshing generates new magnetic fields, mostly over the night side, and they, in turn, induce electrical currents in the ground. Those currents surge out of the ground and into the electrical transmission lines.

The Sun is shooting off, on average, a few coronal mass ejections a day, including one on March 15 that made a direct hit on Earth, generating picturesque nighttime auroras as far south as Colorado but causing no noticeable harm.

NASA's Sun-watching spacecraft keep track of the sunspots, and they can provide some warning of which regions look likely to erupt.

The two hemispheres of the Sun are out of sync. The northern hemisphere has been ahead of the curve, producing a large number of sunspots in late 2011 and has quieted since then, while the southern hemisphere has remained fairly quiet throughout.

Most solar scientists expect the southern hemisphere to perk up, and the number of sunspots to increase again, with the solar maximum arriving in the fall. Such double-peak patterns have appeared in some earlier solar cycles.

"I believe I can say with strong confidence there will be a second peak in 2013," said Douglas Biesecker, a physicist at the Space Weather Prediction Center and the chairman of a panel that issued predictions about the solar cycle.

John Kappenman, an electrical engineer who owns Storm Analysis Consultants, has been warning of potential catastrophe. "In a sense," he said, "we're playing Russian roulette with the Sun."

The New York Times