Fearful relatives vent their outrage

By Reuters in Jindo, South Korea (China Daily) Updated: 2014-04-21 07:27

|

|

Relatives of missing passengers aboard the sunken ferry Sewol cry after listening to a TV news program reporting the names of the victims found dead, at a gymnasium in Jindo, South Korea, on Sunday. Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press |

Kim Ha-na no longer sleeps or eats and is haunted by the voice of her 17-year-old brother, calling frantically to tell her the ferry he was aboard with more than 300 classmates and staff from his high school was sinking.

More than 50 people are now known to have died and about 250, mostly children, are presumed dead in the upturned hull of the stricken vessel that capsized off the southwestern tip of the Korean Peninsula on Wednesday.

Since then, Kim and hundreds of other relatives have spent 24 hours a day waiting helplessly for news in makeshift accommodations at a gymnasium in the port city of Jindo, the center of the rescue operation.

They live and grieve together, packed into the floor space on narrow, thin mattresses. The relatives take to a communal microphone to vent their hopes and anger at government officials over the seemingly slow pace of the rescue and the sketchy information they are given.

Kim's brother, Dong-hyup, was one of 339 students and teachers from Danwon High School on the outskirts of Seoul who were on an annual outing to the subtropical island of Jeju. They made up most of the 476 passengers and crew.

"He called me at 8 am, saying the ship was sinking. Then I lost him," Kim, a 22-year-old student, told Reuters.

The Sewol ferry took more than two hours to sink in calm waters on a well-traveled, 400-km route from the mainland South Korean port of Incheon to Jeju, a journey of more than 13 hours.

Hope and anger

The gym has become a focal point for anger as well as fading hope.

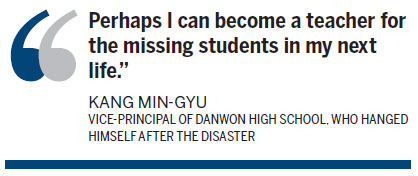

It was also the scene of one more tragic death. Kang Min-gyu, 52, the vice-principal of Danwon High School, disappeared on Thursday and was later found hanged with his belt from a pine tree outside the gymnasium.

Kang, who had been rescued from the sinking ferry, left a heart-rending two-page suicide note, part of which was released by police. In it, he said he could not live while the fate of 200 others was unknown.

"Burn my body and scatter my ashes at the site of the sunken ferry," he wrote. "Perhaps I can become a teacher for the missing students in my next life."

Professional care is available at the site, and there is free Internet and medicine as well as shampoo and soap, but South Korean officials have struggled to fully cope with the overwhelming tragedy.

Officials took DNA swabs from relatives on Saturday, adding to the foreboding that what had been billed as a rescue mission had become an operation to recover and identify bodies.

"It is a group trauma, not just for parents here but for people across the country. It's not going to be over in one or two months. It is leaving a big scar," said a 48-year-old woman surnamed Yoon who is a member of a team of counselors at the gym.

She declined to give her full name. Many Koreans do not wish to see their full names used in the news media when commenting on sensitive issues.

Endless reminders

In the gymnasium, there's no escape from the tragedy. Endless TV news and footage from the rescue is played on four huge television screens that relay information to the hundreds grieving inside the gym.

When relatives obtained underwater footage of the rescue taking place in the murky, tidal waters around the Sewol after divers said they had seen bodies, Coast Guard officials were jeered by those watching.

President Park Geun-hye was heckled by some when she visited the site on Thursday, a rare occurrence in a hierarchical country where respect for authority is still important.

The microphone set up on a stage is now used more to give voice to frustration and anger than for expressing any hope, and it channels the rising emotions of those waiting largely in fear.

"It will be a miracle if they are alive. I just want to hug my child's body," a father said from the stage to applause from other waiting relatives.

At other times, they grab at the collars of coast guard members, who try to explain that they are doing their best to find the missing.

Often they just weep, looking at pictures of lost sons or daughters on their cellphones.

"What does everything here mean?" Kang Dae-hyun, whose son Hyuck is missing, kept murmuring to himself. "It's so worthless."

- 65 dead, 237 missing in S. Korean ferry sinking accident

- Divers find bodies inside sunken ferry

- Communications between sunken ferry, traffic center disclosed

- Death toll surges to 56 as divers enter sunken S.Korean ferry

- 10 more bodies found for sunken S.Korean ferry

- Sunken ferry's operator involved in numerous accidents

- Death toll of South Korean ferry sinking rises to 33

- One more body found near sunken ferry

- Sunken ferry relatives give DNA swabs to help identify victims

- Survivors of sunken ferry show serious signs of depression: hospital

- First bodies found within cabins of S. Korean sunken ferry