Deep in the valley, school gets a new life

By Li Lianxing in Nairobi (China Daily Africa) Updated: 2014-11-21 13:22

A Hong Kong university used speedy, high-tech construction to rescue kids from crammed classrooms

In the deepest point of Mathare Valley, where Nairobi's second-largest slum is located, a sparkling new building stands in stark contrast to the run-down shanties made of dark sheets of iron that surround it.

This is phase two of a project organized by Mcedo-Beijing School that was designed by the architecture department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and sponsored by the Kenya-China Economic and Trade Association.

Locals continue to express their wonder that this two-story school building with a capacity of more than 400 students was built from scratch in just four weeks from the end of August at a cost of 1.5 million yuan ($245,000).

After the foundations were laid, heavy cranes were used to put the pre-fabricated structure into place.

Huang Zhengli, a project consultant with the university, says the structure is much lighter than traditional concrete or stone buildings because special light steel was used that was particularly apt for the local terrain.

Apart from the easy construction in an area of 8 square kilometers with a dense population of 500,000, ensuring that it was environmentally friendly was also regarded as critical, given the need to keep energy use and waste to a minimum.

"Producing the steel sheets that have been used here generates more carbon dioxide per kilogram than is the case with traditional construction materials, but the building is so much lighter than a traditional one, only one-sixth of it, so overall emissions can be halved or even cut by up to two-thirds," Huang says.

Electric power in the slum is highly unreliable, so the building was designed with special glass that lets huge amounts of natural sunshine into classrooms.

Huang became aware of the school when she was doing an internship with United Nations-Habitat, the UN human settlement program, three years ago. The school urgently needed upgrading because by the end of 2007, more than 400 students were having lessons in a building with a capacity of just 250, she says.

"The atmosphere in the old building was stifling, and I don't think children can study properly in that kind of environment."

In 2007, the Chinese embassy in Kenya donated the school building, the first phase of the project, that was designed for about 250 students from surrounding areas, providing primary and secondary education. Lunch for students is free thanks to support from the World Food Programme.

However, by 2012 the number of students surpassed 580 and an expansion beyond the first-phase, two-story concrete building was even more urgent.

"I thought it was a good chance to promote our new research technology," Huang says, adding that her team at the Chinese University of Hong Kong had tested the construction technology in many places in China over the previous six years, including in areas struck by natural disasters.

"The technology can also be used in remote forests as a conservation measure, with the designs and materials chosen depending on local physical conditions. All these projects have been carried out in areas where such conditions required a short construction period and involved particular structural demands, and they all worked out well."

The physical complexities related to building in the Mathare Valley had made the project even a bigger challenge than she had imagined, she says.

Given the slum's living conditions, it was important to think carefully about how to make best use of the limited resources, she says. This presented a chance for new technology to be brought into play and for the university to be bold enough to experiment.

"We were really surprised at how quickly the locals we worked with were able to grasp how our building techniques worked. You can find prefabricated buildings elsewhere in Kenya, but with the quality of ours and in a place like Mathare, it's very new. But the locals we employed picked up the skills effortlessly, and after being shown how to assemble different parts, saw the job through to completion."

It took two weeks to lay the foundations, and the rest was completed within four weeks, which was much shorter than had been expected, even if such a project in China could be completed in 10 days, Huang says.

Kelvin Otieno, a construction team leader hired locally, says that when he saw the plans, he imagined the building task would be difficult, but it turned out to be almost the simplest construction job he has worked on.

"I learned quickly and think it has turned out to be a very distinctive building. If we can put up something like this in Mathare, I can't see why we can't do it in other places, and I can now show others how it is done."

Africa now presents huge opportunities for those involved in urban development, and Huang is keen to introduce this and other new technologies elsewhere in Africa.

"It can be used not just in slums but in other urban areas, and that includes for community centers, hotels, even private dwellings," she says.

A feasibility study was done before the Mathare project began, but the team was unclear about how things would turn out, Huang says. "For example, we had to find out how much it would be to hire plant and equipment, and to recruit local labor, and we had no idea what the workers would be like and how they would relate to us. We prepared every piece of material in China because we were unsure about what materials were readily available and how much they would be, and that resulted in higher costs."

According to the Kenyan government, building a community center in a downtown area would cost about $350 a square meter, but for this project the cost was $300, Huang says.

But Patrick Warui, an architecture student at the Technical University of Kenya and an intern who saw the construction first hand, says costs could have been a lot lower if some materials had been bought locally.

"They imported everything this time so you can reduce the costs a lot, otherwise such a project would be unrealistic anywhere else in the country."

Efficiently implemented in Kenya, such projects might engender a whole production industry chain that would not only bring products to people, but more jobs and advanced technologies, he says.

lilianxing@chinadaily.com.cn

|

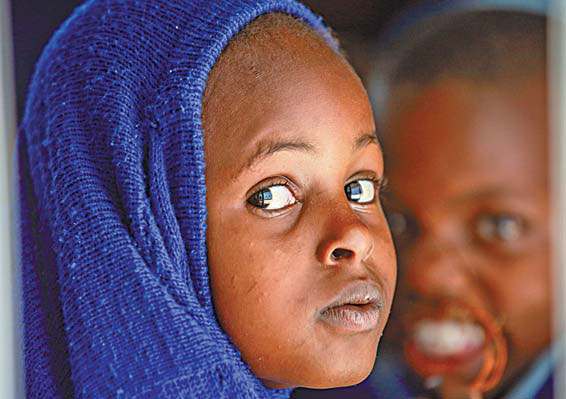

Students at the new classroom of the Mcedo-Beijing School in Mathare, Nairobi. The school has more than 630 students, all from the slum. Zhang Chengliang / China Daily |

|

A photo through a window of two students at the Mcedo-Beijing School. Zhang Chengliang / China Daily |

(China Daily Africa Weekly 11/21/2014 page8)