Steeled for long-term profits

By Li Lianxing (China Daily Africa) Updated: 2014-11-21 09:14

A Chinese factory in Tanzania counts on quality and efficiency to overcome stiffening competition

Africa's urban skylines are changing every day as new buildings spring up, pushed by continuous growth in many areas over the past decade.

That has boosted demand for steel products such as rods. Companies are also making these products locally to keep construction costs under control and supplies adequate.

|

Hong Yu Steels (Tanzania) Co Ltd has more than 300 local workers and about 50 technicians from China. Provided to China Daily |

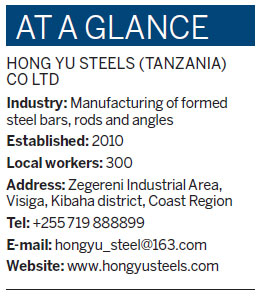

Ni Liangjun, 52, chairman of the private Hong Yu Steels (Tanzania) Co Ltd, says demand is still growing. While competition is cutting into prices, he says a long-term development plan that emphasizes quality is benefiting his business and should help it expand into neighboring countries.

Hong Yu produces 5,000 metric tons of steel bars, rods and related products monthly at its factory on a 100,000 square meter site in the Kibaha area 50 kilometers west of Tanzania's economic hub of Dar es Salaam.

Before coming to Africa in 2010, Ni was running a transportation and shipbuilding business in East China's Zhejiang province.

"I had never been to Africa before, but I knew Africa was a good market. Initially I was introduced to Tanzania to invest in a quarry but later I found the steel industry was more promising because the country was a net importer," he says.

They estimated that Tanzania needed at least 100,000 tons of steel rods annually, but the country had only a few small-scale factories. The country's exact figure for steel production was hard to pin down, but, according to the World Steel Association, Tanzania's neighboring countries of Kenya and Uganda each had annual production capacity of 20,000 to 30,000 tons.

And the quality of locally produced steel bars was lower because of outdated production technology being used, meaning they could be employed only in buildings of one or two stories.

Given Ni's aim to grow into surrounding markets in the future, it was important that he ensure the factory's longevity by using advanced technologies. So he brought in a completely automated production line with a maximum annual capacity of 100,000 tons.

"I felt demand in this country was quite promising based on construction projects and changes in the skyline that can be easily seen and felt," he says. "Our machines all mold and roll automatically, ensuring production efficiency."

At the same time, the market did not require the scale seen in China, where smelters often have a capacity of more than 200 tons. Each of Ni's three smelters in Tanzania has a capacity of only five tons. But he said the scale is appropriate for current production, and expansion would depend on future market development.

"Since we are establishing a long-term business in this place, quality is of the highest priority for us. So we are not following either the local or the Chinese standard, but the relatively higher British standard reflected in bending, hardness and stretching tests," he says.

The factory's raw materials are partially imported from Turkey and the United States, but Ni says he is focusing on the establishment of a local steel-recycling network for his supplies.

"We have a large demand for raw materials, so the most convenient way for us is to collect waste iron and steel objects locally. I couldn't calculate how many people are collecting raw materials for us nationwide, but we buy 4,000 to 5,000 tons of raw materials from local agents every month," he says.

Another area emphasized by Ni is the training of Tanzanian workers. Because the factory uses relatively advanced machines, it takes more time and energy to transfer skills to local workers, Ni says.

"Most of the work is done by machines, which is more convenient than traditional production lines. But we have to teach local workers both basic mechanical knowledge and a computer-controlled management system, which is difficult for us," he says.

There are more than 300 local workers at the factory, led by about 50 technicians from China. They are divided into teams with one to two Chinese technicians responsible for teaching 10 local workers.

Ni says at this stage, local workers can monitor most of the computerized management system, but only Chinese technicians have the skills to resolve system glitches.

"We still let local workers focus on basic mechanical problems," he adds.

Hong Yu launched its investment in Tanzania in 2010 and the factory started operating in 2013, which means it took nearly three years to complete the construction and generate production.

"We have learned a lesson, that one has to be very realistic about the local investment environment when putting together your investment strategy because the hardware and software may give you many challenges in many ways," he says. "We had estimated one and a half years as our setup time given that such a factory would take only six months to finish in China. But it took us nearly three years, which greatly increased our costs."

The location of Hong Yu's factory was designed to be a special industrial zone equipped with infrastructure and transportation facilities, but that didn't reflect reality. It took nearly a year to get a working power grid installed.

"There are a limited number of factories operating in the zone, so we had to manage the building of some basic infrastructure. And other aspects, including transportation and container clearance, may also take a much longer time than you expect," he says. "Also, you have to prepare two or three more sets of key spare parts for the machines because you can't find them in the local market. This also increased our costs."

Still, their investment promises to generate rewards in the long run, says Ni.

Miao Liujie, 33, vice-general manager and marketing manager of the company, says the reason for operating a business in Africa is clear: "Looking back at China, this industry there has a lot of competition and the market is also quite saturated. So there is a dire need to explore a new market. When you look at Africa's economic development in the past few years and its regional integration, you find the demand for this product and the market is developing quite fast.

"High investment costs will lead to big rewards, but the premise is that you have to have a long-term development strategy and integrate your business into the local business culture and society."

At times, even the weather presents a challenge. Parts of Tanzania and Kenya experience two rainy seasons - long rains from April to June and shorter rains from November to December.

But while production at the factory only started a year ago, their products already have found their place in the market, Miao says.

"We have slower times during the two rainy seasons, but in general, we can guarantee monthly production of 5,000 tons. Clients come to find us, and we don't have to go out and find them at this stage," he says.

Competition is deepening as more industries come in, so profits are dropping. But Hong Yu intends to stand out due to its long-term strategy and good quality.

"When we did market research in 2010, 12 millimeter steel rod was sold at $1,100 per ton in the market, but last year the price dropped to $760. And we estimate the price will come down to $690 per ton by the end of the year," Miao says. "So the only way we can ensure our operation in this country is to sustain our quality and increase the productivity."

lilianxing@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Africa Weekly 11/21/2014 page19)