Beyond Marco Polo and Matteo Ricci

By Thomas Rosenthal (China Daily Europe) Updated: 2014-06-27 07:31

Bumps along the way, but China and Italy have much to gain in working together

All the Italian prime ministers who have been in power recently have planned or paid official visits to China, even though their governments have had relatively short life spans.

Mario Monti landed in China in March 2012. Matteo Renzi recently visited Beijing, a trip that Enrico Letta had been forced to cancel at the end of February. That was when the former replaced the latter at the helm of a broad coalition government.

The trips have come as Italy has struggled to return to a growth path through structural reform that is - according to consensus along Italy's fragmented political spectrum - the only way to avoid decline. Reforms are also crucial to regain attractiveness vis-a-vis foreign investors from China and elsewhere.

Renzi's trip to China was his first out of the Euro-Mediterranean area and came ahead of Italy's six-month European Union presidency starting next month. During that period, Italy will be under the spotlight.

In October, Milan will host the Asia-Europe Meeting, an interregional forum, and from next May to the end of October, it will stage the World Expo, where China has confirmed a high-profile presence with three pavilions - the national, corporate and Vanke pavilions. Italy will also be under pressure to accelerate its reform efforts as promised by Renzi.

Italy looked at Germany's Agenda 2010 reforms started by Gerhard Schroeder in 2003 when it kicked-off a virtuous economic cycle thanks to fiscal prudence, cuts in labor costs, and structural reforms that enabled the country to digest the reunification. It turned it into the economic powerhouse that the Chinese look at with admiration. However, Italians, not unlike many South Europeans, view Germany as the inflexible guardian of austerity that keeps them bogged down in a seemingly never-ending recessionary cycle notwithstanding the efforts they have made.

Renzi hinted on a number of occasions that he would stick to the so-called Maastricht parameters on national finances but that he would also seek more flexibility from Europe to support Italy's growth.

Italy was one of the countries more responsive to the "Going for Growth" recommendations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the club of advanced economies, that pushed badly needed economic reforms in 2011-2012, according to an OECD report signed by Pier Carlo Padoan, Italy's economy and finance minister.

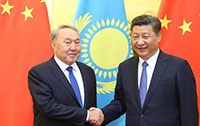

That stance has been lauded by the EU and the global economic community, and acknowledged by ratings agencies. During his visit in China on June 10 and 11, Renzi cashed in on congratulations of President Xi Jinping for the reforms that advanced his economy. Both would admit, however, that a lot still needs to be done.

Despite repeated reform attempts, Italy still ranks 65th, moving up two positions, in the World Bank's "Doing Business In" report, which measures the ease of doing business across economies. The Heritage Foundation, a US conservative think-tank, ranks Italy 86th in its Economic Freedom Index.

Since 2007, the year before the global financial crisis began, foreign direct investment in Italy declined by 58 percent to 12.4 billion euros ($16.8 billion) according to Censis, an Italian research center.

But investment flows into Italy from China dropped considerably only in 2012, the year of the debt crisis, when Italy witnessed net capital flight, according to Chinese Ministry of Commerce data elaborated by the Italy China Foundation.

This means that overall, apart from 2012, during the economic crisis, Italy's opportunity-risk trade-off has tilted more toward opportunities in the eyes of Chinese investors and financial authorities.

It would not be surprising to learn that the Chinese government had intervened to hinder investment flows toward Italy in 2012, given the non-fully convertible renminbi, in a year that was relatively difficult for the domestic economy. which was also a difficult year for China's domestic economy.

So Italy has taken advantage of a rebound in Chinese investments, in the context of China's go-global policy and diversification of foreign currency denominated assets, that were earmarked but then postponed because of Italy's debt crisis, as the Italy China Foundation forecast in its annual report on the Chinese economy.

It was China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the nation's foreign currency safe-box, acting as a sovereign fund, that invested heavily in oil producer Eni and utility Enel, both controlled by the Italian government. These portfolio operations were followed by Shanghai Electric's acquisition of Ansaldo Energia, part of the Italian government-controlled conglomerate Finmeccanica.

Surprisingly, all these bets were placed on a sector - energy - that is far from Italy's more alluring resources in the eyes of the Chinese. Those strategic assets include know-how in manufacturing, "Made in Italy" brands, Italy's market and its points of access to the Mediterranean and continental Europe.

But despite the public rhetoric stressing Marco Polo and Matteo Ricci as historically bridging these two ancient civilizations, behind closed doors, bilateral concerns dominate, and many of Renzi's staff believe that it is time to "change direction", using the slogan that won him popularity and votes during the recent European parliamentary elections.

Political stability is crucial to this end: Chinese authorities need to be able to shake hands with credible counterparts who will remain in power for more than a few months or a year. Renzi appears to be in a more stable position than his recent predecessors.

China has a large trade surplus with Italy, and despite Italy's efforts to rebalance its economic relations through attraction of capital from China, Italy still scares off foreign investors. Factors that drive away capital are not only economic fundamentals but also diffuse corruption, political instability, political scandals, pervasive organized crime, red tape, the slowness of court procedures and a rigid labor market.

China is still considered a competitor by representatives of Italian industry as their country, a traditionally export-oriented economy, lost global market share to China. Many Italians still tend to point their finger at "unfair" Chinese competition rather than looking at the decreasing competitiveness and productivity of the domestic economy.

In a report last year, quite shockingly, an American Pew Institute survey said Italians held the world's second-worst favorable attitude toward China - though distant from first-placed Japan. These negative perceptions definitely do not make the country more receptive toward Chinese investment, even though the benefits to Italy that could accrue from Chinese investment would probably help change this mind-set.

Italy appears in better shape than many other European economies in terms of a "return to the real economy", to manufacturing, a call rising nowadays from both sides of the Atlantic. Italy is the sixth manufacturing power, in terms of added value created, and the 11th ranked world exporter. China is the world's biggest producer and exporter of goods.

Indeed, Italy and China are competitive in manufacturing, but like all competitors they have substantial benefits to reap from cooperation. Italy and China have mutually advantageous, intra-industry trade in many sectors such as machinery and equipment, with China exporting relatively lower-end, labor-intensive machinery and Italy exporting higher-end, skill-intensive machinery.

China is a developing economy with its problems and needs. This creates learning and market opportunities through business interaction. "Combining Italian technology and China's vast market is not only a benefit to both countries but also helps in opening third markets in other countries," Renzi said in Shanghai.

Italy can boast manufacturing excellence in many fields and can provide the opportunity for Chinese manufacturers to upgrade their skill set and output in line with the aims spelled out in China's 12th Five-Year plan (2011-15), as well as aiding China's efforts to become an advanced, knowledge-based economy. In fields such as agricultural mechanization, green technologies, sustainable urbanization and healthcare, the two governments, given the complementary natures of their economies, are engaged in close cooperation. At the same time, China needs to be more open to foreign investment and goods and should improve its intellectual property protection system in order to provide incentives to companies trading and investing in and sharing knowledge with China.

The author is director of the Research center of the Italy China Foundation. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.