Finding a family in the fog of war

By Cai Hong and Shan Yi (China Daily) Updated: 2015-08-24 07:48

|

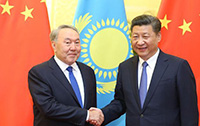

Sumie Ikeda sheds tears as she leads a group of Japanese citizens on a visit to the graves of their adoptive Chinese parents in Fangzheng, Heilongjiang province, in July. Wang Kai / Xinhua |

Thousands of former 'war orphans', Chinese-born Japanese children left behind when their parents returned to Japan in 1945, have spent their lives attempting to find their true antecedents. For one woman, that journey took more than 40 years and involved three changes of name, as Cai Hong and Shan Yi report from Tokyo.

One day in 1953, a policeman arrived at the home of Sumie Ikeda in Mudanjiang city in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang. He asekd yo speak with her mother, and requested that the 8-year-old girl leave the room so the adults could speak freely.

Ikeda complied, but hid behind a door to eavesdrop. The conversation stunned her.

"Your daughter is Japanese, isn't she?" the officer asked.

Even though her mother refuted the accusation, for Ikeda - who was known as Xu Ming at the time - the exchange corroborated the strange stories her neighbors and classmates had told her. Some said she had been adopted. Others simply called her "the Japanese".

She demanded to know the truth, and was distraught to discover that the policeman had been correct. At the time, just eight years after the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggresion (1937-45), recollections of the Japanese army's bruality during the occupation of China were still raw.

"Not all Japanese people commit evil deeds. The Japanese soldiers are bad men, but the Japanese people are not," her mother said, in attempt to calm her.

Despite making many efforts, the only thing Ikeda was able to learn about her biological parents was that they had left her behind when they evacuated Mudanjiang after Japan's surrender on Aug 15, 1945.

Initially, Ikeda had a happy life with her adoptive family, but everything changed when her foster father fled after his business failed. Ikeda began to take care of her mother, who had bound feet and could hardly walk, let alone earn a living.

They lived on the breadline. Late one night, Ikeda awoke to discover her foster mother attempting to hang herself. Dissuaded by the sight of Ikeda's tears, she she pledged to stay alive for the sake of her adopted daughter.

The dire circumstances led Ikeda to try to find her biological parents and ask for help. "Although I knew absolutely nothing about them, I always prayed toward the east, which, as I knew, is where Japan is," she said.

In 1953. China began repatriating "war orphans" - children left behind by Japanese soldiers and civilians - but Ikeda refused to go because she didn't want to leave her foster family and, equally important, she had no one to turn to in her home country.

After graduating from a teaching college in 1962, Ikeda was sent to a school in a remote woodland district far from home, where she married a woodcutter, settled down and had three children.