Q&A: How were the Japanese war crimes tried? (30)

(chinadaily.com.cn) Updated: 2015-11-19 17:36Q&A: How were the Japanese war crimes tried?

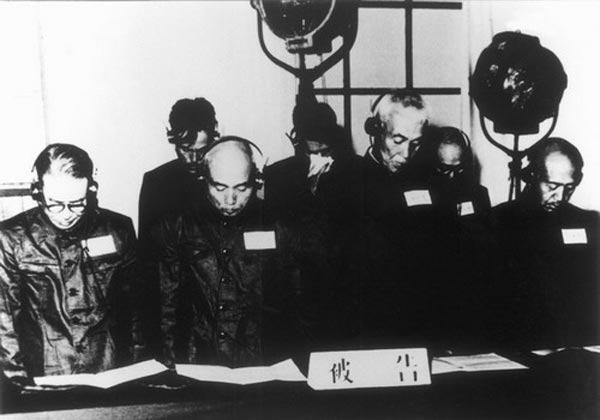

A: After the end of World War II, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) was established in Tokyo.

On January 19, 1946, General Douglas MacArthur issued the Special Proclamation and approved the Charter of the IMTFE, clearly setting out the three types of acts for which there would be individual responsibility: conventional war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity.

On April 29, the IMTFE officially prosecuted 28 Class A war criminals. The Tokyo Trials lasted two and a half years, concluding on November 12, 1948. In the end, 25 defendants had been tried and given verdicts. Seven of them were hanged (Hideki Tōjō, KōkiHirota, Kenji Doihara, SeishirōItagaki, Heitarō Kimura, Iwane Matsui, and Akira Mutō). Sixteen were sentenced to life imprisonment (Sadao Araki, Kingoro Hashimoto, ShunrokuHata, HiranumaKiichirō, Naoki Hoshino, Okinori Kaya, Kōichi Kido, KuniakiKoiso, Jirō Minami, Takazumi Oka, Hiroshi Ōshima, KenryōSatō, Shigetarō Shimada, Toshio Shiratori, YoshijirōUmezu, and Teiichi Suzuki). In addition, Shigenori Tōgō was sentenced to 20-year and Mamoru Shigemitsu 7-year imprisonment. On the morning of December 23, 1948, seven Class A war criminals were hanged at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo.

In December 1945, the National Government and the Far Eastern and Pacific Sub-Commission of the United Nations War Crimes Commission formed the Commission on the Handling of War Crimes and set up military tribunals to try war criminals in China. Trials were held in Baoding, the Northeast, Nanjing, Guangzhou, Jinan, Wuhan, Taiyuan, Shanghai, and Taiwan. From late 1945 to the end of December 1947, these military tribunals handled the cases of 2,435 Japanese war criminals. They handed down verdicts in 318 cases and refrained from prosecuting 661 cases. After the review of the Ministry of Defense of the National Government, death sentences were delivered in 110 cases.

Military tribunals were also set up in other countries that had been subjected to Japanese invasion to try Class B and Class C war criminals, including Russia (in Khabarovsk), Singapore, the Philippines (in Manila), Burma (in Rangoon), and Vietnam (in Saigon, which is today known as Ho Chi Minh City). Statistics show that a total of 5,423 Japanese war criminals were prosecuted by the Allies. Among them, 4,226 were sentenced, of which 941 were given the death penalty.

From December 25 to 30, 1949, the special military tribunal of the Soviet Union conducted trials of 12 war criminals.

The United Kingdom set up special military tribunals in Hong Kong and Singapore to try Japanese war criminals, prosecuting 118 in Hong Kong and 446 in Singapore. Among those prosecuted, 133 were sentenced to death, two to life imprisonment, and 369 to fixed-term imprisonment. Tomoyuki Yamashita, who had been the commander of the 14th Area Army when Japanese troops surrendered, was arrested and executed in the Philippines.

The Dutch government prosecuted 995 Japanese war criminals across Indonesia, sentencing 226 to death, 30 to life imprisonment, and 697 to fixed-term imprisonment.

The US prosecuted 1,453 Japanese war criminals, sentencing 140 to death, and Australia prosecuted 939 Japanese war criminals, sentencing 153 to death.

Generally speaking, the Tokyo Trials were relatively fair. They embodied the common will of the anti-fascist Allied countries and the principle of justice in international law. However, there were also some apparent shortcomings.

First, Japanese Emperor Hirohito was not held to account for his part in the War. He shouldered ultimate responsibility for the Japanese war of aggression and the atrocities of Japanese troops, and played an important role in planning the war: "When Japan invaded northeast China in 1931, or launched a full-scale war of aggression in 1937, or committed any other crime in China, including the Nanking massacre, the ‘Three Alls' policy (kill all, burn all, and loot all), the torture of POWs, the killing of civilians, and the development and use of chemical weapons, Emperor Hirohito did not take any measure to stop but rewarded the perpetrators." Despite his position as supreme commander in the war of aggression, Emperor Hirohito was not charged with any offense.

Second, "crimes against humanity" was not used as an individual account of prosecution. This crime refers to Japan's brutal acts during its rule over Korea, Taiwan, and other colonies and especially within occupied China. For example, the brutal "Three Alls" policy resulted in thousands of atrocities, the indiscriminate bombing of residents of defenseless cities, and the use of forced labor and "comfort women" as the sexual slaves of the Japanese troops. Although the International Military Tribunal for the Far East recognized that "crimes against humanity" was a crime in international law of war, the prosecution did not press charges for these atrocities committed under Japanese colonial rule.

Third, war criminals of biological and chemical warfare were not severely punished. During the War, over 5,000 Japanese troops openly defied international conventions by carrying out biological and chemical warfare in China, and participating in the research, production, and use of such weapons, including cruel and inhumane experiments on live human beings. Nonetheless, many Japanese war criminals escaped the force of law and due punishment. Even more unpalatable was that some Japanese military officers involved in the research and development of biological weapons wrote and published academic papers on the basis of data they had gained from their "live experiments" in China, and dozens of those who had committed such brutalities obtained doctorate degrees in medicine.